Bubo virginianus virginianus, B. v. subarcticus, B. v. lagophonus, B. v. pallescens

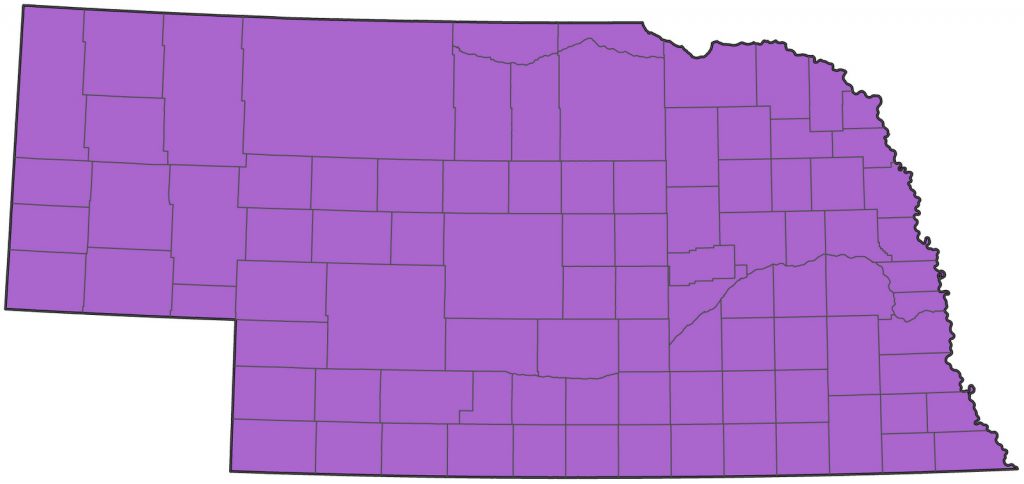

Status: Common regular resident statewide. Rare regular winter visitor statewide.

Documentation: Specimen: virginianus, UNSM ZM12752, 4 Nov 1902 Lancaster Co; subarcticus, UNSM ZM-16270 12 Mar 1990 Cuming Co.

Taxonomy: Fifteen subspecies are recognized (AviList 2025); those whose ranges potentially include Nebraska are lagophonus of the northern Rocky Mountains from Alaska south through British Columbia to northeast Oregon, central Idaho south to the Snake River, and northwestern Montana, wintering south and east as far as Colorado and Texas, subarcticus of Mackenzie and northeastern British Columbia east to Hudson Bay and south to the northwestern Great Plains, pallescens of central California and deserts of southeast California through southern Utah to western Kansas and south to Mexico, pinorum of southern Idaho south of the Snake River to northern Arizona and northern New Mexico, and virginianus, of Minnesota east to Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island and south through eastern Kansas and eastern Texas to Florida.

Nebraska Great Horned Owls are virginianus (resident), subarcticus (winter visitor, intergrading resident), lagophonus (winter visitor), and pallescens (intergrading or vagrant breeder, post-breeding vagrant).

Assignment to subspecies of Nebraska breeding birds is complicated by complex, clinal, and probably shifting subspecies boundaries on the Great Plains (Pyle 1997, Taverner 1938, Robbins and Rush 2021); indeed, Pyle (2025) synonymized the five subspecies listed above as virginianus, which obviates the difficulties of identification discussed below.

Robbins and Rush (2021) point out that, like other species such as Blue Jay, Eastern Screech-Owl, and Broad-winged Hawk, virginianus is likely to have expanded its range westward across most of the Great Plains, including Nebraska, since earlier range delineations limiting virginianus to the southeastern quarter of the state (Swenk 1937, AOU 1957, Pyle 1997, Dickerman 1993); most breeding Great Horned Owls in Nebraska are probably virginianus or genetically near virginianus.

Previous authors (Swenk 1937, AOU 1957, Rapp et al 1958) proposed that western subarcticus (including “occidentalis”) occupied parts of Nebraska north and west of virginianus. Oberholser (1904) described the range of occidentalis as from western Minnesota to southeastern Oregon, and south in the prairies to Kansas. However, use of occidentalis was suppressed as a synonym of subarcticus (Dickerman 1991), which required renaming at least some Great Horned Owl populations, in this case those in the range of “occidentalis” from the Snake River, Idaho southward; Dickerman and Johnson (2008) proposed the name B. v. pinorum. This subspecies occupies the region to the south of lagophonus and at higher elevations in the southern parts of the range of pallescens, and seems unlikely to occur in Nebraska. Thus, the identity of paler breeding birds in northwestern Nebraska but within the range set out by Oberholser (1904) is conjectural. Some authors (e.g. Pyle 1997, Dickerman 1993) consider owls in this region (“occidentalis”) to be intergrades between southeastern individuals of subarcticus and northern individuals of pallescens, but it seems more logical according to current taxonomy and known ranges they are intergrades of subarcticus and virginianus.

According to Artuso et al (2020), irruptions from Saskatchewan and Alberta involving striking southeasterly movement occur when population crashes of snowshoe hare (Lepus americanus) occur in boreal forest and aspen parkland. These authors also state that it is not known whether such owls return to their areas of origin in spring, but also state: “typically, emigration is unidirectional”. Of interest in this context is a report of two pale birds on nests in extreme southeast Sheridan Co and in northwest Garden Co 20 Apr 2003; these were photographed by Ty Smedes and may have been previous winter immigrants that had not returned to their natal areas (Silcock 2003). Indeed, Taverner (1938) stated that “occasionally these winter wanderers remain to breed in localities far from their natural range”; a nesting season specimen “typical of pallescens” collected in Pawnee Co was thought to be an example of this phenomenon (Dickerman 1993).

In winter, the pale, occasionally almost white (Bent 1938), birds from the northern parts of the range of subarcticus, previously known as “wapacuthu” (incorrectly: Artuso et al 2020), exhibit a tendency to disperse eastward in fall and winter, beginning when young are abandoned by adults (Swenk 1937, AOU 1957, Haecker et al 1945). Three nestlings of subarcticus banded in Saskatchewan were recovered in Nebraska, around 850 miles away (Dickerman 1993). Swenk (1937) cited 11 specimens of subarcticus (as “wapacuthu”) dated 11 Nov-1 Mar, from all parts of the state. Two of these, #2542 and #10686, are in the Hastings Municipal Museum. Another thought to be this subspecies was a roadkill in Hamilton Co 21 Jan 2012, likely associated with the huge Snowy Owl invasion that winter. A “very pale gray” bird was seen in Dundy Co 25 Oct 2004 and sightings of one described as an “Arctic” Great Horned Owl in southeast Washington Co 19 Dec 2017 and 14 Jan 2018 were probably of the same bird. A pale bird was photographed 16 Jan 2019 in Keith Co, and another 19 Jan 2021 in Lincoln Co. One was photographed near Hershey, Lincoln Co 29 Jan-16 Feb 2022.

The northwestern US race lagophonus also appears casually in winter (AOU 1957). Swenk (1937) cited eight records of lagophonus statewide in the period 28 Oct-mid Feb, including a specimen #2679 in the Hastings Municipal Museum.

Occurrence of the pale southerly race pallescens in Nebraska is equivocal (Swenk 1938). Swenk (1937) cited three specimens of pallescens, from Adams Co 7 Dec 1933 and 19 Oct 1934 and Saunders Co 9 Dec 1934, although he later re-examined the 1933 Adams Co specimen and concluded it was a small example of subarcticus. Swenk (1938) also re-examined the Saunders Co specimen, noting it was small and pale, and that “for the present at least, its identification as a post-breeding season wandering individual of pallescens will be permitted to stand”. Dickerman (1993) suggested that pallescens may breed in western counties of Nebraska, but that data were “weak”. A nesting season specimen “typical of pallescens” collected in Pawnee Co was thought to be an example of fall or winter migration followed by residency (see above) (Dickerman 1993).

Resident: Great Horned Owls are relatively evenly distributed residents statewide. It occupies the edges of deciduous and coniferous forests as well as open savannah. Mature woodland, including woodlots at farmsteads, shelterbelts, and larger parks in towns and cities often host Great Horned Owls. Although highly adaptable as a predator and therefore broadly distributed, one limiting factor to its distribution may be the availability of appropriate nest sites such as large abandoned nests of other species in mature trees, cavities in stumps of fallen trees, and ledges on cliffs.

It has been suggested (Robbins and Rush 2021) that eastern virginianus, like other eastern forest species (Blue Jay, Eastern Screech-Owl, Broad-winged Hawk) is expanding westward as succession occurs in riparian corridors.

- Breeding Phenology:

- Territorial fighting: 17 Jan

- Copulation: 20 Jan-10 Feb

- Incubation: 18 Jan-15 May

Eggs: 18 Jan-13 Apr (Mollhoff 2022)

Nestlings: 15 Mar-9 Jun

Fledglings: 17 Apr-18 Aug (late dates are of begging fledglings)

Winter: See Taxonomy for discussion of winter visitors. CBC counts indicate the abundance of this species; high counts are 31 at Norfolk 20 Dec 1986, and 30 at both Omaha 26 Dec 1987 and Lincoln 16 Dec 1990.

Images

Abbreviations

CBC: Christmas Bird Count

UNSM: University of Nebraska State Museum

Literature Cited

American Ornithologists’ Union [AOU]. 1957. The AOU Check-list of North American birds, 5th ed. Port City Press, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Artuso, C., C.S. Houston, D.G. Smith, and C. Rohner. 2020. Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.grhowl.01.

AviList Core Team, 2025. AviList: The Global Avian Checklist, v2025. https://doi.org/10.2173/avilist.v2025.

Bent, A.C. 1938. Life histories of North American birds of prey. Part Two. Bulletin of the United States National Museum 170. Dover Publications Reprint 1961, New York, New York, USA.

Dickerman, R.W. 1991. On the validity of Bubo virginianus occidentalis Stone. Auk 108: 964–965.

Dickerman, R.W. 1993. The subspecies of the Great Horned Owls of the central Great Plains, with notes on adjacent areas. Kansas Ornithological Society Bulletin 44: 17-21.

Dickerman, R.W., and A.B. Johnson. 2008. Notes on Great Horned Owls Nesting in the Rocky Mountains, with a Description of a New Subspecies. Journal of Raptor Research, 42: 20-28. https://doi.org/10.3356/JRR-06-75.1.

Haecker, F.W., R.A. Moser, and J.B. Swenk. 1945. Checklist of the birds of Nebraska. NBR 13: 1-40.

Mollhoff, W.J. 2022. Nest records of Nebraska birds. Nebraska Ornithologists’ Union Occasional Paper Number 9.

Oberholser, H.C. 1904. A revision of the American Great Horned Owls. Proceedings U.S. National Museum 27: 177-192.

Pyle, P. 1997. Identification Guide to North American Birds. Part I, Columbidae to Ploceidae. Slate Creek Press, Bolinas, California, USA.

Pyle, P. 2025. A Practical Subspecies Taxonomy for North American Birds. North American Birds 76(1).

Rapp, W.F. Jr., J.L.C. Rapp, H.E. Baumgarten, and R.A. Moser. 1958. Revised checklist of Nebraska birds. Occasional Papers 5, Nebraska Ornithologists’ Union, Crete, Nebraska, USA.

Robbins, M.B. and I.N. Rush. 2021. The status of the migratory Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus subarcticus) in Kansas and Missouri, with comments on the breeding distribution of subspecies in the Great Plains. Kansas Ornithological Society Bulletin 72: 33-37.

Silcock. W.R. 2003. Spring Field report, March-May 2003. NBR 71: 58-96.

Swenk, M.H. 1937. A study of the distribution and migration of the Great Horned Owls in the Missouri Valley Region. NBR 5: 79-105.

Swenk, M.H. 1938. Some Additional Observations on the Races of the Great Horned Owl. NBR 6: 7-8.

Taverner, P.A. 1938. An Explanation of the Local Variations Occurring in the Great Horned Owl. NBR 6: 8-9

Recommended Citation

Silcock, W.R., and J.G. Jorgensen. 2025. Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus). In Birds of Nebraska — Online. www.BirdsofNebraska.org

Birds of Nebraska – Online

Updated 8 Sep 2025