Poecile atricapillus septentrionalis

Status: Fairly common regular resident statewide. Fairly common winter visitor statewide, common Missouri River Valley counties.

Documentation: Specimen: UNSM ZM6484, Nov 1893 Lancaster Co.

Taxonomy: Nine subspecies are recognized (AviList 2025); those occurring in the central US and Canada are garrinus from central Idaho to south-central Montana south to southeastern Utah and central New Mexico, septentrionalis from southern Yukon and northeast Colorado east to central Manitoba and central Kansas, and atricapillus from southeast Manitoba to eastern Kansas east to Prince Edward Island and northern New Jersey.

Two subspecies have been reported in Nebraska: eastern atricapillus breeding in southeastern Nebraska (“Omaha”, AOU 1957), and septentrionalis, the Rocky Mountain subspecies, breeding essentially across the state. Bruner et al (1904) stated: “In extreme eastern Nebraska an occasional chickadee is found nearer to atricapillus than [septentrionalis], but such are not plentiful and most of the eastern Nebraska birds are intergrades.”

For a discussion of possible hybrids with Mountain Chickadee and the occurrence of Mountain Chickadee-like songs sung by phenotypic Black-capped Chickadees in Nebraska, see Black-capped x Mountain Chickadee (hybrid).

A family group frequenting the Phil Swanson yard in Papillion, Sarpy Co during Jun 2021 included a brown-capped juvenile along with normally colored black-capped individuals. This may be only the second such bird on record in North America; the other, in New York Jul 2004, was first identified as a Boreal Chickadee (P. hudsonicus), but later re-identified as a Black-capped Chickadee; this phenomenon and its possible causes were discussed by Silcock and Swanson (2021).

Resident: Most Black-capped Chickadees breeding in Nebraska are resident, as indicated by banding studies. Of 78 Nebraska banding records examined for various times of the year, all recoveries were at the place of banding (Patuxent Banding Lab data); a similar result was noted by Brown et al (1996) in Keith Co.

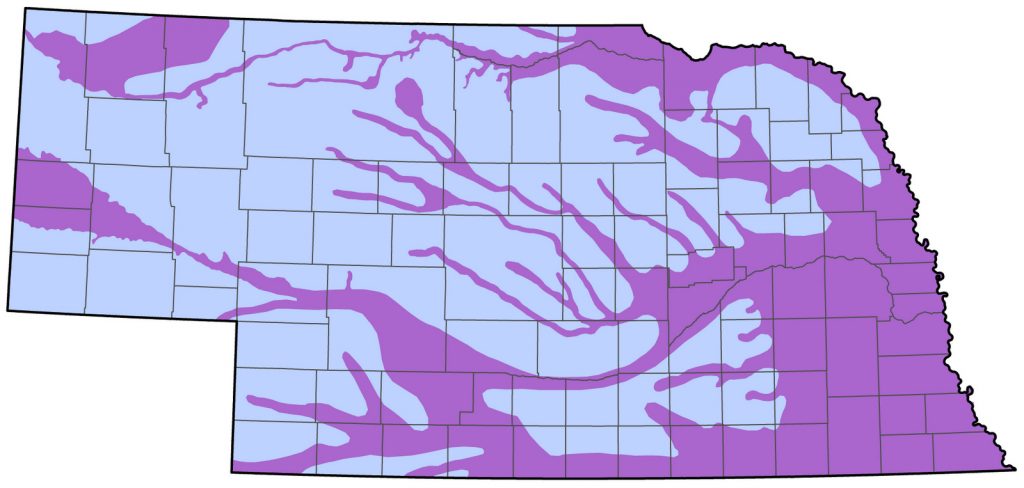

Breeding birds are distributed in riparian corridors throughout the state but are least numerous in the western Sandhills, southwest, and Panhandle away from the Pine Ridge and North Platte River Valley (Mollhoff 2016), areas where riparian woodlands are lacking. Distribution is local in the Rainwater Basin; Jorgensen (2012) noted the species is “fairly common along the watercourses that intersperse the RWB; absent in most of the RWB.” This status was similar to that which Tout (1902) observed as he mentioned that chickadees “are not found away from streams” in York County. Black-capped Chickadee distribution, particularly in areas with marginal habitat, was likely reduced by the effects of West Nile Virus in the early 2000s (see Comments, below).

- Breeding Phenology:

Nest Building: 18 Mar-26 May

Copulation: 13-29 Apr

Eggs: 31 Mar-30 May

Nestlings: 11 Apr-7 Jul

Fledglings: 1 May-30 Jul

- High counts: 39 on Fairfield Road, Brown Co 23 Jun 2022, and 29 at Gilbert-Baker WMA, Sioux Co 11 Jul 2022.

Spring, Fall: Long-distance movements of Black-capped Chickadees do occur; these involve mostly young birds undergoing a post-fledgling dispersal, although irregular movements occur every 2+ years that likely result from a decrease in food resources following a period of higher food availability that resulted in a high level of breeding success (Foote et al 2020). These events are best termed “irruptions” rather than true migration (Foote et al 2020). High Counts (below) suggest movements occur in Apr and Sep-Oct. At Wildcat Hills NC in 2024 BCR banders found a “noticeable increase” in numbers of this species in mid-Sep, accompanied by a low recapture rate of four from 17 banded.

- High counts:

- Spring, east: 46 at Fontenelle Forest, Sarpy Co 2 Apr 2022, 44 there 1 Apr 2017, 37 at DeSoto NWR, Washington Co 10 Apr 2021, and 35 at Fontenelle Forest 3 Apr 2010.

- Fall, east: 36 at Fontenelle Forest 27 Sep 2023, 30 there 4 Oct 2021, 30 at Cunningham Lake, Douglas Co 20 Oct 2023, 28 at Branched Oak Lake, Lancaster Co 18 Nov 2021, and 27 at Cunningham Lake 24 Nov 2024.

- Spring, west: 29 at Gilbert-Baker WMA, Sioux Co 29 Mar 2020.

- Fall, west: 37-42 in Sowbelly Canyon, Sioux Co 24 Aug-19 Oct 2019, 27 there on 3 Sep and 27 Sep 2017, and 25 at Chadron SP, Dawes Co 26 Sep 2017.

Winter: In Nebraska, CBC data show a far more even distribution of chickadees in winter than that indicated by BBS data in summer, as well as a concentration in the east. It is generally assumed that birds from further north winter in Nebraska (Rapp et al 1958, Johnsgard 1980), and indeed chickadees are more common in winter in the northwest (Rosche 1982), as exemplified by recent midwinter tallies in Sowbelly Canyon and Ponderosa WMA of 93 on 6 Jan 2021 and 74 on 30 Dec 2020 respectively.

Chickadees also become noticeable at locations where they are not conspicuous in summer, especially where feeders are provided. Furthermore, measurements of netted birds at Bellevue, Sarpy Co during winter 2003-2004 indicated an influx of the subspecies septentrionalis (Betty Grenon, Rick Schmid, personal communication), which “occasionally wanders south in winter” (Foote et al 2020).

Highest CBC counts are at Omaha, Douglas Co, where 822 were counted 1987-88 and 657 in 1989-90.

- High counts: 50 at Arbor Lodge SHP, Otoe Co 20 Feb 2017, 50 at Hummel Park, Douglas Co 29 Dec 2023, 40 at Neale Woods, Douglas Co 28 Dec 2022, and 40 at Cunningham Lake, Douglas Co 26 Dec 2024.

Comments: Black-capped Chickadees declined sharply over most of Nebraska around 2002-2003 coincident with the arrival of West Nile Virus, providing strong circumstantial evidence for the cause of the decline. BBS trend analysis show the species declined statewide at an annual rate of -5.66 (95% C.I.; -10.48, -1.12) during 2003-2013 (Sauer et al 2014). However, definitive evidence of a link was limited initially (Nick Komar, personal communication), but subsequent studies have shown West Nile Virus to be linked to declines in numbers of chickadees and other species (LaDeau et al 2007, Kilpatrick et al 2007).

Even though declines were noted over most of the state, the numbers of Black-capped Chickadees recorded on CBCs in the Missouri River Valley remained near average during the early to mid-2000s. Suggested explanations for the apparent lack of chickadee declines in this region included birds moving in during winter from elsewhere (see above) or some degree of immunity in Missouri River Valley birds that might have been previously exposed to West Nile Virus (Tom Labedz, personal communication). In addition, variations in the prevalence of West Nile Virus across Nebraska may have been associated with variations in mosquito species diversity and abundance (T.J. Walker, Tony Leukering, personal communication; Jorgensen 2016). Jorgensen (2016) presented data from the Centers for Disease Control that showed the highest rates of West Nile Virus incidence in the United States included most of western and central Nebraska, but incidence was less in the southeast. Differential West Nile Virus incidence in humans was attributed to weather and climate cycles that influence the abundance of Culex mosquitoes, an important disease vector, on the Great Plains.

By 2009-2010 Black-capped Chickadee numbers appeared to be recovering in many areas of eastern and central Nebraska where declines had been previously observed, notably Lancaster Co; the Branched Oak Lake-Seward CBC averaged 169 chickadees in its first 10 years, but only 23.5 from 2003 through 2008 (Gubanyi 2020). However, numbers increased subsequently, to peak at 99 on 16 Dec 2011, but another decline followed, to 31 in 2018; an increase, but only to 63 in 2020 and 66 in 2021 ensued. The 2012 “comeback” was well-documented by meticulous tracking of chickadees on many outings in 2012 by Larry Einemann, who found chickadees on 50 out of 72 trips, where in the previous several years none had been found on similar numbers of trips. BBS trend analysis for the period 2005-2015 (Sauer et al 2017) supported the “comeback”, showing an annual increase of 2.68% per year (95% C.I.; -1.89, 7.79) compared to the sharp decline noted above for the years 2003-2013.

Chickadees re-appeared in 2012 in a few western locations after long absences: since 2003 near North Platte, Hall Co, 2004 north of North Platte, Lincoln Co, and “for a few years” in Scotts Bluff Co. On the other hand, in parts of central Nebraska relatively low numbers of chickadees were observed in 2012; one at a Grand Island, Hall Co feeder 23 Aug was a “big deal” and two at another feeder there 26 Aug were the first there for several years. Also in 2012, one at Rowe Sanctuary, Buffalo Co 25 Sep was the first there for 10+ years. Further afield, in east-central Nebraska, two at a feeder in Dodge Co in 2012 were “like the good old days”, and a single there 21 Feb 2019 was “first for years”. Three in a Dixon Co yard 1 Apr 2023 were the “first since West Nile Virus” (Jan Johnson, personal communication).

However, some areas in central Nebraska have been slow to recover or have suffered another recent decline. The Harlan County Reservoir CBC, Harlan Co, averaged 99 per year 1996-2001 but only one was found on the 2018 CBC, following a new low of 12 in 2016. Surprisingly also, the Lake McConaughy CBC, Keith Co, found only one chickadee in its 30 Dec 2018 iteration; peak tally there was 84 in 2001. Numbers have not recovered on the Branched Oak Lake-Seward CBC; in the first 10 years of the count >100 chickadees were counted, but no count since 2002 has reached that level. CBCs in 2019 across the state showed low numbers (birds per party hour) in 2019-2020, with varying recovery since. Variability year to year may be due to regional movements in response to changing regional conditions.

Clem Klaphake provided a citation (https://news.mongabay.com/2018, referring to Carolina Chickadee) that noted: “In gardens with less than 70% of native plants by biomass, chickadee populations crashed, because the insects they usually eat cannot live on nonnative trees and flowers.” Applicability of this hypothesis in Nebraska is unclear, however.

Images

Rosche 1974

Abbreviations

BBS: Breeding Bird Survey

BCR: Bird Conservancy of the Rockies

CBC: Christmas Bird Count

NC: Nature Center

SHP: State Historical Park

SP: State Park

UNSM: University of Nebraska State Museum

Literature Cited

American Ornithologists’ Union [AOU]. 1957. The AOU Check-list of North American birds, 5th ed. Port City Press, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

AviList Core Team, 2025. AviList: The Global Avian Checklist, v2025. https://doi.org/10.2173/avilist.v2025.

Brown, C.R., M.B. Brown, P.A. Johnsgard, J. Kren, and W.C. Scharf. 1996. Birds of the Cedar Point Biological Station area, Keith and Garden Counties, Nebraska: Seasonal occurrence and breeding data. Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences 23: 91-108.

Bruner, L., R.H. Wolcott, and M.H. Swenk. 1904. A preliminary review of the birds of Nebraska, with synopses. Klopp and Bartlett, Omaha, Nebraska, USA.

Foote, J.R., D.J. Mennill, L.M. Ratcliffe, and S.M. Smith. 2020. Black-capped Chickadee (Poecile atricapillus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.bkcchi.01.

Gubanyi, J. 2020. History of the Seward-Branched Oak Lake Christmas Bird Count 1993-2020. NBR 87: 162-172.

Johnsgard, P. A. 1980. A preliminary list of the birds of Nebraska and adjacent Great Plains states. Published by the author, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, USA.

Jorgensen, J.G. 2012. Birds of the Rainwater Basin, Nebraska. Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA.

Jorgensen, J.G. 2016. Status review of the Black-billed Magpie (Pica hudsonia) in Nebraska. Nongame Bird Program of the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA.

Kilpatrick A.M., M.A. Meola, R.M. Moudy, and L.D. Kramer. 2008. Temperature, viral genetics, and the transmission of West Nile virus by Culex pipiens mosquitoes. PLoS Pathogens 4:e1000092

LaDeau, S.L., A.M. Kilpatrick, and P.P. Marra. 2007. West Nile virus emergence and large-scale declines of North American bird populations. Nature 447: 710-713.

Pyle, P. 1997. Identification Guide to North American Birds. Part I, Columbidae to Ploceidae. Slate Creek Press, Bolinas, California, USA.

Rapp, W.F. Jr., J.L.C. Rapp, H.E. Baumgarten, and R.A. Moser. 1958. Revised checklist of Nebraska birds. Occasional Papers 5, Nebraska Ornithologists’ Union, Crete, Nebraska, USA.

Rosche, R.C. 1974. Mixed-up chickadees. NBR 42: 80

Rosche, R.C. 1982. Birds of northwestern Nebraska and southwestern South Dakota, an annotated checklist. Cottonwood Press, Crawford, Nebraska, USA.

Sauer, J.R., J.E. Hines, J.E. Fallon, K.L. Pardieck, D.J. Ziolkowski, Jr., and W.A. Link. 2014. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, results and analysis 1966-2012 (Version 02.19.2014). USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center 2014. Available from http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/bbs.

Sauer, J.R., D.K. Niven, J.E. Hines, D.J. Ziolkowski, Jr, K.L. Pardieck, J.E. Fallon, and W.A. Link. 2017. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 – 2015 (Nebraska). Version 2.07. USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, Maryland, USA.

Silcock, W.R., and P. Swanson. 2021. A brown-capped Black-capped Chickadee (Poecile atricapillus) in Sarpy County, Nebraska. NBR 89: 136-139.

Tout, W. 1902. Ten years without a gun. Proceedings of Nebraska Ornithologists’ Union 3: 42-45.

Recommended Citation

Silcock, W.R., and J.G. Jorgensen. 2025. Black-capped Chickadee (Poecile atricapillus). In Birds of Nebraska — Online. www.BirdsofNebraska.org

Birds of Nebraska – Online

Updated 2 Sep 2025