Spizella passerina passerina, S. p. arizonae

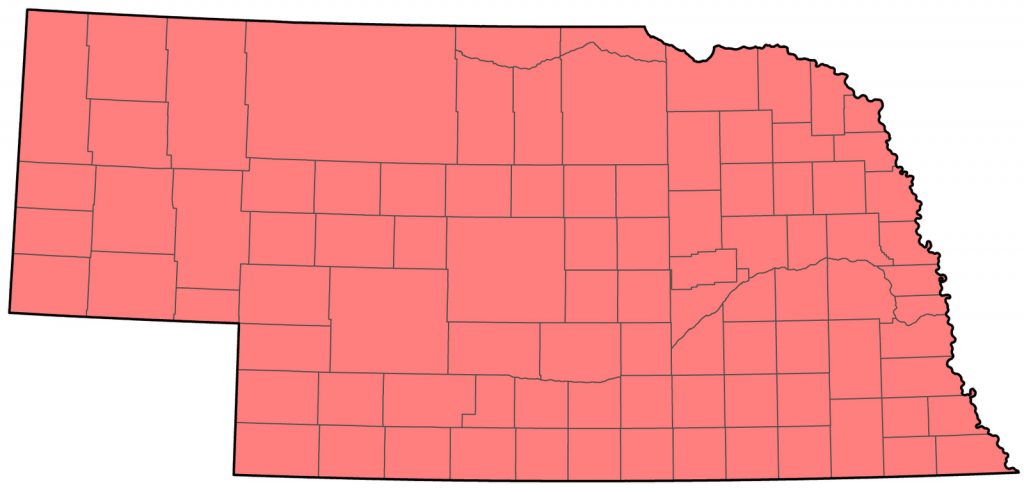

Status: Abundant regular spring and fall migrant statewide. Common regular breeder statewide, uncommon western Sandhills and southern Panhandle. Rare casual winter visitor southeast.

Documentation: passerina: specimen UNSM ZM7426, 27 Apr 1901 Lincoln, Lancaster Co; arizonae: specimen Carnegie Museum of Natural History P23637 Squaw Canyon, Sioux Co.

Taxonomy: Five subspecies are recognized (Middleton 2020, AviList 2025), three in Mexico and two in the US: arizonae breeding and wintering from Alaska to Ontario and south to California and Texas, and passerina, breeding and wintering from Ontario to south Texas and east to Newfoundland and Florida.

In Bruner’s time (Bruner et al 1904), Chipping Sparrows bred at opposite ends of the state, presumably arizonae in the west on the Pine Ridge and passerina in the east. Bent (1968) stated that passerina breeds south from northeast Minnesota to eastern Kansas (see also Johnston 1965). Swenk (1906) collected a breeding pair “decidedly of the western race” at Glen, Sioux Co, 6 Aug 1905; the location of these specimens is currently unknown.

Oberholser recognized darker populations of arizonae, breeding from Alaska and Manitoba south to Utah, northern Colorado, and central Nebraska as boreophila (Middleton 2020). If boreophila is recognized, it could account for Chipping Sparrows that form “a large wedge dividing the eastern and western races on the western plains (Wright 2019). It is not known which subspecies of Chipping Sparrow have moved into central Nebraska during the last 100 years; it seems likely most are arizonae (boreophila) or its intergrades with passerina.

Pyle (2025) synonymized arizonae and passerina based on their not meeting the generally accepted 75% rule for subspecies diagnosability.

Floyd (2011) raised the possibility that Chipping Sparrows of subspecies arizonae breeding in Colorado undergo an eastward molt migration in Jul onto the plains, and that other subspecies, in particular eastern passerina, do not perform such a migration.

Chipping Sparrow hybrids with Clay-colored and Field Sparrow are occasionally reported, although none for Nebraska. There are several records of Chipping x Clay-colored Sparrow hybrids, nearest to Nebraska one in Larimer Co, Colorado (eBird.org, accessed Dec 2023). Hybrids of Chipping Sparrow and Field Sparrow are rare; only four are cited in eBird, including one in Kiowa Co, Colorado (eBird.org, accessed Dec 2023).

Spring: Mar 11, 11, 12 <<<>>> summer

Chipping Sparrows typically arrive in late Mar and peak numbers occur in early May. There are several earlier reports in Mar; such reports require documentation because this species is routinely confused with other species, namely American Tree Sparrow and singing Dark-eyed Juncos. However, one in Lancaster Co 1-5 Mar 2010 was photographed, as was another there 1-4 Mar 2019, and there were several early reports in 2012 after a mild winter, including 3 Mar at Fairmont, Fillmore Co and 7 Mar at Dakota City Cemetery, Dakota Co. Earliest dates in Webster Co were 6 Mar 1930, 11 Mar 1931, 12 Mar 1929, and 13 Mar 1927 (Ludlow 1935).

In areas of the southwest where breeding is uncommon, migrants depart by late May (Brown and Brown 2001).

- High counts: 542 in Hall Co 13 May 2006, 508 in Sarpy Co 11 May 1996, 433 in Hall Co 11 May 2002, and 410 at Calamus Reservoir, Loup Co 7 May 2005.

A single flock of 250 was in Omaha 28 Apr and 300 were in a weed patch near Beatrice 4 May 2013.

Summer: Chipping Sparrow has adapted to the arrival of Europeans by nesting in planted trees, usually conifers, around human settlement, both rural and urban (Thompson and Ely 1992). Bent (1968) suggested that the “population of today is many times that of pre-Columbian North America.” This change has resulted in expansion of its breeding range in Nebraska from essentially east of the 98th meridian and on the Pine Ridge at the turn of the century (Bruner et al 1904) into most other parts of Nebraska. Short (1961) pointed out that most of this spread had been in towns, and that the species was still scarce at that time in the southwest (below). BBS trend analysis (Sauer et al 2020) reflects the increase and shows the species has increased 2.79% (95% C.I.; 3.96, 5.12) annually in Nebraska 1966-2019.

Mollhoff (2001, 2016) showed that between the first breeding bird atlas (1984-1989) and the second (2006-2011), large areas of the Sandhills and southwest that had no breeding season reports are now occupied. There are still counties in the western Sandhills such as Box Butte Co and in the southwest, notably Perkins and Hayes, where there were no breeding season reports 2006-2011 (Mollhoff 2016). Survey transects at Fort Niobrara NWR, Cherry Co in 1991 and 1992 recorded no Chipping Sparrows, but breeding is common there as of 2021 (Renee Tressler, personal communication). As of 2023, there are about 20 records for Jun-Jul for the western Sandhills (eBird.org, accessed Dec 2023).

Until recently, nesting was unknown south of the Platte River Valley west of Kearney, Buffalo Co; it was considered a migrant in Keith Co as late as 2000 (Brown and Brown 2001). Breeding reports have increased, however; confirmed breeding was reported in Harlan Co in 1999, and in Dundy Co 2006-2011 (Mollhoff 2016). Chipping Sparrows were found at only 20 of 453 stops in southeast Lincoln County breeding bird surveys in 2009 (T.J. Walker, personal communication); no evidence for breeding was noted, although reports in Jun 2014 and 2015 for Hitchcock, Frontier, and Gosper Cos suggest gradual occupation by breeding birds of the southwest. As of 2023, there are about 40 records for Jun-Jul along Frenchman Creek and the Republican River west of McCook, Red Willow Co in the southwest (eBird.org, accessed Dec 2023).

- Breeding phenology:

Copulation: 29 Jul - Nest Building: 3 May-28 Jun

Eggs: 3 May-19 Aug (Mollhoff 2022)

Nestlings: 11 May-20 Aug

Fledglings: 14 Jun-1 Sep

Fall: summer <<<>>> Nov 16, 17, 17

Migration ends statewide by early Nov; reports after mid-Nov should be documented. The latest specimen date is 30 Oct 1909 (UNSM ZM10463). There are about 15 later reports with details through Dec; typically, Chipping Sparrows that linger into winter are single immatures at feeders.

Migration begins in Aug, although it is difficult to determine early departure dates because of local breeders and migrants from elsewhere. A recent hypothesis suggests an early molt migration strategy for several passerine species which have populations in drier parts of the inter-mountain western United States (Donahue 2007). Indeed, Floyd (2011) documented eastward movement in Jul towards the plains in eastern Colorado and Kansas and showed that these birds were essentially all adults; it is generally inferred that if adults move away from breeding areas in fall before juveniles, molt migration is taking place (Floyd 2011). Thus, in areas of southwest Nebraska where there are few breeding Chipping Sparrows, Jul records of adults may be of molt migrants from the Rockies; however, since subspecies arizonae breeds in western Nebraska, the presence of breeding Chipping Sparrows in, for example, the Sandhills, would make detection of molt migrants difficult if not impossible.

The abundance of this species during fall migration was indicated by the banding by Bird Conservancy of the Rockies personnel of 151 individuals 19 Aug-2 Oct 2013 at Wildcat Hills NC, Scotts Bluff Co; there were only 11 additional recaptures from previous years, one of which was first banded in 2008.

- High counts: 700 near Burwell, Garfield Co 5 Oct 2002, 330 in Sheridan Co 24 Sep 1994, and 300 at East Ash Creek Canyon, Dawes Co 5 Sep 2015.

Winter: There are several reports mid-Jan through Feb that suggest overwintering, all in recent winters. These are 29 Dec 1982-31 Jan 1983 Omaha, Douglas Co feeder (Williams 1983), 7 Jan and 20 Feb 2017 at a Bellevue, Sarpy Co feeder, 27 Jan-1 Feb 2021 Milford, Seward Co, 27-28 Jan 2025 Lancaster Co, 5 Jan and 13 Feb 2021 Omaha, Douglas Co, and 2-14 Feb 2019 (1-2) at Mahoney Park, Lincoln, Lancaster Co.

Additional early Jan dates are 3 Jan 2011 Adams Co, 5 Jan 2020 Lake McConaughy, Keith Co, 6-13 Jan 2008 Lincoln, Lancaster Co, 11 Jan 2018 Omaha, Douglas Co, and 15 Jan 2024 Douglas Co. One in Clay Co 26 Feb 2005 may have been an early migrant.

Images

Abbreviations

BBS: Breeding Bird Survey

NC: Nature Center

NWR: National Wildlife Refuge

UNSM: University of Nebraska State Museum

Literature Cited

AviList Core Team, 2025. AviList: The Global Avian Checklist, v2025. https://doi.org/10.2173/avilist.v2025.

Bent, A.C. 1968. Life histories of North American Cardinals, Grosbeaks, Buntings, Towhees, Finches, Sparrows, and allies. Bulletin of the United States National Museum 237. Three Parts. Dover Publications Reprint 1968, New York, New York, USA.

Brown, C.R., and M.B. Brown. 2001. Birds of the Cedar Point Biological Station. Occasional Papers of the Cedar Point Biological Station, No. 1.

Bruner, L., R.H. Wolcott, and M.H. Swenk. 1904. A preliminary review of the birds of Nebraska, with synopses. Klopp and Bartlett, Omaha, Nebraska, USA.

Donahue, M. 2007. Migrants, Mono Lake, Monsoons, and Molt. Birding 39: 34-40.

Floyd, T. 2011. Mid-summer Dispersal, Nocturnal Movements, and Molt Migration of Chipping Sparrows in Colorado: Taxonomic Implications and Conservation Applications. Colorado Birds 45: 181-197.

Johnston, R.F. 1965. A directory to the birds of Kansas. Miscellaneous Publication No. 41. University of Kansas Museum of Natural History, Lawrence, Kansas, USA.

Ludlow, C.S. 1935. A quarter-century of bird migration records at Red Cloud, Nebraska. NBR 3: 3-25.

Middleton, A.L. 2020. Chipping Sparrow (Spizella passerina), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.chispa.01.

Mollhoff, W.J. 2001. The Nebraska Breeding Bird Atlas 1984-1989. Nebraska Ornithologists’ Union Occasional Papers No. 7. Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA.

Mollhoff, W.J. 2016. The Second Nebraska Breeding Bird Atlas. Bull. Univ. Nebraska State Museum Vol 29. University of Nebraska State Museum, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA.

Mollhoff, W.J. 2022. Nest records of Nebraska birds. Nebraska Ornithologists’ Union Occasional Paper Number 9.

Pyle, P. 2025. A Practical Subspecies Taxonomy for North American Birds. North American Birds 76(1).

Sauer, J.R., W.A. Link and J.E. Hines. 2020. The North American Breeding Bird Survey – Analysis Results 1966-2019. U.S. Geological Survey data release, https://doi.org/10.5066/P96A7675, accessed 27 Jul 2023.

Short, L.L., Jr. 1961. Notes on bird distribution in the central Plains. NBR 29: 2-22.

Swenk, M.H. 1906. Some Nebraska bird notes. Auk 23: 108-109.

Thompson, M.C., C.A. Ely, B. Gress, C. Otte, S.T. Patti, D. Seibel, and E.A. Young. 2011. Birds of Kansas. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas, USA.

Williams, F. 1983. Southern Great Plains Region. American Birds 37: 314-317.

Wright, R. 2019. Sparrows of North America. Peterson Reference Guide. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston and New York.

Recommended Citation

Silcock, W.R., and J.G. Jorgensen. 2025. Chipping Sparrow (Spizella passerina). In Birds of Nebraska — Online. www.BirdsofNebraska.org

Birds of Nebraska – Online

Updated 9 Sep 2025