Accipiter cooperii

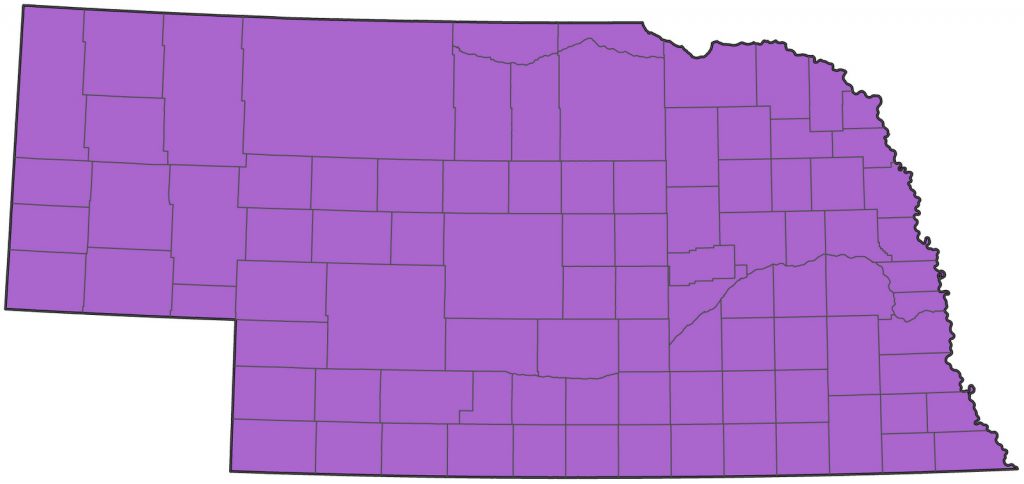

Status: Fairly common, locally common, regular spring and fall migrant statewide. Fairly common regular breeder and winter visitor statewide.

Documentation: Specimen: UNSM ZM12499, 17 May 1909 Lancaster Co.

Taxonomy: No subspecies are recognized (Gill et al 2023).

Changes Since 2000: There has been a noticeable increase in breeding season reports, especially in urban settings, as this species has expanded its range and numbers since the 1990s (see Summer). This increase has occurred around the same time as Eurasian Collared-Dove populations have increased, as noted by David Leatherman in Colorado (post to COBIRDS 3 May 2021) and Brush Freeman in Texas (post to TEXBIRDS 11 Jul 2022).

Spring: The presence of wintering birds makes determination of initiation of spring movement difficult, as does the presence of summering birds for the end of spring migration. Available data do not show a clear peak in movement, although Kent and Dinsmore (1996) and Rosenfield et al (2020) show spring migration extending from mid-Mar through mid-May.

- High counts: 6 in Sarpy Co 2 May 2003, and 6 in Kearney Co 21 Mar 2019.

Summer: This species utilizes woodland of all types, but is “notoriously difficult to survey” (Curtis et al 2006), which may explain the paucity of reports through the 1990s. Nesting was reported in Thomas Co 1946-48 (Bray 1994), Ducey (1988) showed only 12 nesting records through 1987, Mossman and Brogie (1983) believed Cooper’s Hawk to be a probable nester in the Niobrara Valley Preserve in 1982, and Mollhoff showed only two “confirmed” records (both from the Republican River Valley) and one “probable” record out of 19 summer reports 1984-1989 (Mollhoff 2001). Rosche (1982) considered it casual in summer with no evidence of breeding on the Pine Ridge.

Mollhoff (2001) noted that while there were several reports 1984-1989 from the Republican River Valley, a few along the Niobrara Valley and Pine Ridge, and a few in the southeast, large areas of suitable habitat in the state were apparently not utilized. While breeding might not be expected in the relatively tree-less Sandhills region, it is apparent that breeding numbers in Nebraska had been moderate at best through the 1980s, with perhaps 20 records. However, starting in the 1990s, there was a significant population increase and range expansion of the species throughout much of its North American range, most noticeably in the form of breeders colonizing urban and suburban areas (Rosenfield et al 2020). This increase has been reflected in Nebraska as well, where, since 1990, there have been at least 26 breeding records through 2015, 13 of these in Omaha and Lincoln. BBS data show an increase of 3.23% (0.62-6.01) per year 1966-2019 (Sauer et al 2020).

In addition to the breeding records discussed above, there are at least 50 breeding season (10 Jun-14 Aug) reports on record, about half in the southeast and the rest clustered on the Pine Ridge, in the Niobrara Valley, and in Lincoln Co. Such reports are suggestive of breeding in those areas.

- Breeding Phenology:

- Courtship: 15 Mar-12 Jun

- Nest-building: 7 Mar-7 May

Copulation: 10 Mar

Eggs/incubation: 30 Mar-25 Jun (Mollhoff 2022)

Nestlings: 25 May-28 Jul

Fledglings: 15 Jun-31 Jul.

Fall: This species is a regular but uncommon fall migrant statewide. Movement is evident beginning in Sep and continues into early Nov, with peak numbers in Sep and early Oct. Data from the Hitchcock Hawk Watch, just across the Missouri River from Washington Co, Nebraska, show an average count per fall of only 237 Cooper’s Hawks compared to 960 Sharp-shinned Hawks (Hawkcount.org).

- High counts: 6 at Zorinsky Lake, Douglas Co 6 Sep 2020, and 6 at Eagle Ridge Park, Sarpy Co 13 Sep 2022.

Winter: Wintering birds occur statewide, although Rosche (1982) considered it a “very rare” winter visitor in the Panhandle. Fewer Cooper’s than Sharp-shinned Hawks are in the state during the CBC period; CBC data 1990-2015 indicate a 1.7/1 ratio of Sharp-shinned to Cooper’s, suggesting that Cooper’s Hawks winter further south than Sharp-shinned Hawks. High statewide CBC totals are recent, apparently reflecting the increasing population trend in this species; all-time high totals were 25 in both 2014-2015 and 2015-2016 and increased notably to 43 in 2017-2018 but declined to 34 in 2022-2023 (Paseka 2023). Numbers are at their lowest in Jan, when the species is rare or absent some years, as noted for Keith Co by Rosche (1994).

Images

Abbreviations

BBS: Breeding Bird Survey

CBC: Christmas Bird Count

UNSM: University of Nebraska State Museum

Literature Cited

Bray, T.E. 1994. Habitat utilization by birds in a man-made forest in the Nebraska Sandhills. Master’s thesis. University of Nebraska-Omaha, Omaha, Nebraska, USA.

Curtis, O.E., R.N. Rosenfield, and J. Bielefeldt. 2006. Cooper’s hawk (Accipiter cooperii). Account 75 in A. Poole, editor. The birds of North America online. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York, USA. <http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/075> (Note: superseded by Rosenfield et al 2020- see below).

Ducey, J.E. 1988. Nebraska birds, breeding status and distribution. Simmons-Boardman Books, Omaha, Nebraska, USA.

Gill, F., D. Donsker, and P. Rasmussen (Eds). 2022. IOC World Bird List (v 12.2). Doi 10.14344/IOC.ML.12.2. http://www.worldbirdnames.org/.

Kent, T.H., and J.J. Dinsmore. 1996. Birds in Iowa. Publshed by the authors, Iowa City and Ames, Iowa, USA.

Mollhoff, W.J. 2001. The Nebraska Breeding Bird Atlas 1984-1989. Nebraska Ornithologists’ Union Occasional Papers No. 7. Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA.

Mollhoff, W.J. 2022. Nest records of Nebraska birds. Nebraska Ornithologists’ Union Occasional Paper Number 9.

Mossman, M.J., and M.A. Brogie. 1983. Breeding status of selected bird species on the Niobrara Valley Preserve, Nebraska. NBR 51: 52-62.

Paseka, D. 2023. 2022-2023 Christmas Bird Counts. NBR 91: 27-41.

Rosche, R.C. 1982. Birds of northwestern Nebraska and southwestern South Dakota, an annotated checklist. Cottonwood Press, Crawford, Nebraska, USA.

Rosche, R.C. 1994. Birds of the Lake McConaughy area and the North Platte River valley, Nebraska. Published by the author, Chadron, Nebraska, USA.

Rosenfield, R.N., K.K. Madden, J. Bielefeldt, and O.E. Curtis. 2020. Cooper’s Hawk (Accipiter cooperii), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.coohaw.01.

Sauer, J.R., Link, W.A., and Hines, J.E. 2020. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Analysis Results 1966 – 2019: U.S. Geological Survey data release, https://doi.org/10.5066/P96A7675.

Recommended Citation

Silcock, W.R., and J.G. Jorgensen. 2023. Cooper’s Hawk (Accipiter cooperii). In Birds of Nebraska — Online. www.BirdsofNebraska.org

Birds of Nebraska – Online

Updated 24 Dec 2023