Numenius borealis

Status: Extinct. Formerly abundant regular spring migrant central. Formerly rare regular fall migrant central.

Documentation: Specimen: HMM 2469, Apr 1880 Hamilton Co.

Taxonomy: No subspecies are recognized (AviList 2025).

Records: Eskimo Curlew is probably extinct; there are no accepted records for North America since 1962 (O’Brien et al 2006), although Gill et al (2020) listed more recent sightings. Banks (1977), based on timing of the decline of the species, suggested climate cooling in the 1880s may have played an important role in addition to spring market hunting.

This species’ former abundance and the unregulated hunting which may have played an important role in its decline are described by Swenk (1915):

“They [flocks] contained thousands of individuals, and would often form dense masses of birds extending for a quarter to a half mile in length and a hundred yards or more in width. When the flock would alight the birds would cover forty to fifty acres of ground. During such flights the slaughter of these poor birds was appalling and almost unbelievable. Hunters would drive out from Omaha and shoot the birds without mercy until they slaughtered a wagon load of them; the wagon being actually filled and often with the sideboards on at that. Sometimes …. their wagons were too quickly and easily filled, so whole loads would be dumped out on the prairie, their bodies forming piles as large as a couple tons of coal …”

It took only about 50 years for this species to disappear from Nebraska. During the 1860s the curlew was still numerous, but “Year by year the birds decreased in numbers, until 1878” after which “they were seen only in small flocks or individually here and there” (Swenk 1915). Two were shot by William Townsley near Harvard, Clay Co 10 Apr 1887, who stated “at that date the birds were becoming so scarce he thought he had better add a pair to his collection before it was too late” (Brooking 1942). Brooking (1942) stated that these two Townsley specimens were part of the four held by HMM at that time, but they are not in the collection as of 2018 (Teresa Kreutzer-Hodson, personal communication). However, a specimen in the Denver Museum of Nature and Science #16414 collected by Townsley 10 miles north of Harvard, Clay Co 10 Apr 1889 may be one of those despite the difference in dates of collection. By the 1890s the curlew was rarely seen and after the turn of the century records are few. In 1911, two females were shot in York Co and seven of a flock of eight were taken in Merrick Co (Swenk 1915), one of which is now a specimen UNSM ZM14114. A “lone bird” was collected near Norfolk, Madison Co 17 Apr 1915 (Swenk 1926) but the current location of this specimen is unknown. The last accepted occurrence of the species in Nebraska was a flock of eight near Hastings, Adams Co 8 Apr 1926 (Brooking 1942; Swenk 1926; Bray et al 1986).

Spring migration was from early Apr through the first half of May, with earliest dates 22 Mar, Apr 1 and 2, but the species was primarily a mid- to late Apr migrant, much like American Golden-Plover. The curlew was found in eastern Nebraska in large numbers, but, like the Buff-breasted Sandpiper, “the chief feeding grounds of these curlews at the time (1877) was (sic) in York, Fillmore and Hamilton Counties,” and their heaviest lines of northward migration was (sic) between the 97th and 98th meridians” (Swenk 1915). Those counties make up a majority of the eastern portion of the Rainwater Basin, and it is likely the species’ area of preference encompassed Clay Co as well (Jorgensen 2007). Burned-over prairies were favored by the Eskimo Curlew, but with onset of agriculture, the species also foraged in newly plowed fields.

Fall records are few, but despite its using the same fall route as Hudsonian Godwit, White-rumped Sandpiper, and American Golden-Plover, like the latter, it appears that a number of Eskimo Curlews did migrate through Nebraska in fall, primarily during the first half of Oct (Swenk 1915).

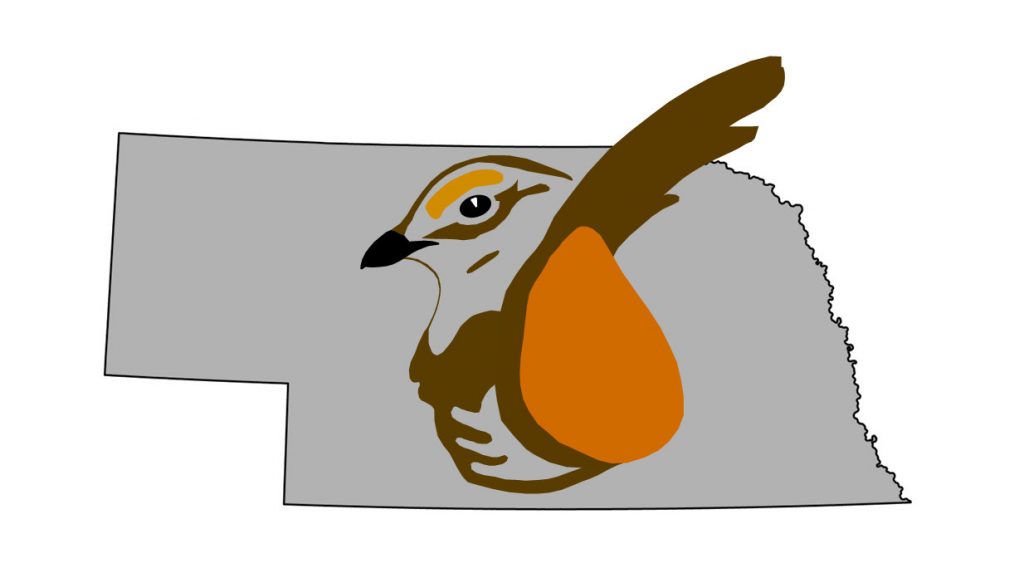

Images

Abbreviations

HMM: Hastings Municipal Museum

UNSM: University of Nebraska State Museum

Acknowledgement

Photograph (top) by Joel G. Jorgensen of two Eskimo Curlews, one of which was taken in Hamilton Co in Apr 1880 and the other in Hall Co 7 Apr 1896. The specimens are housed and maintained at the Hastings Municipal Museum and were legally salvaged or collected. We thank Teresa Kreutzer-Hodson for facilitating the photographing of this specimen for Birds of Nebraska – Online.

Literature Cited

AviList Core Team, 2025. AviList: The Global Avian Checklist, v2025. https://doi.org/10.2173/avilist.v2025.

Banks, R.C. 1977. The decline and fall of the Eskimo Curlew, or did the curlew go extaille? American Birds 31: 127-134.

Bray, T.E., B.K. Padelford, and W.R. Silcock. 1986. The birds of Nebraska: A critically evaluated list. Published by the authors, Bellevue, Nebraska, USA.

Brooking, A.M. 1942. The vanishing birdlife of Nebraska. NBR 10: 43-47.

Gill, R.E., P. Canevari, and E.H. Iversen. 2020. Eskimo Curlew (Numenius borealis), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.eskcur.01.

Jorgensen, J.G. 2007. Buff-breasted Sandpiper (Tryngites subruficollis) abundance, habitat use, and distribution in the Rainwater Basin, Nebraska. Master’s Thesis, University of Nebraska at Omaha, Omaha, Nebraska, USA.

O’Brien, M., R. Crossley, and K. Karlson. 2006. The Shorebird Guide. Houghton Mifflin Co., New York, New York, USA.

Swenk, M.H. 1915. The Eskimo Curlew and its disappearance. Proceedings of Nebraska Ornithologists’ Union 6: 25-44.

Swenk, M.H. 1926. The Eskimo Curlew in Nebraska. Wilson Bulletin 38: 117-118.

Recommended Citation

Silcock, W.R., and J.G. Jorgensen. 2025. Eskimo Curlew (Numenius borealis). In Birds of Nebraska — Online. www.BirdsofNebraska.org

Birds of Nebraska – Online

Updated 10 Jul 2025