Tympanuchus cupido pinnatus

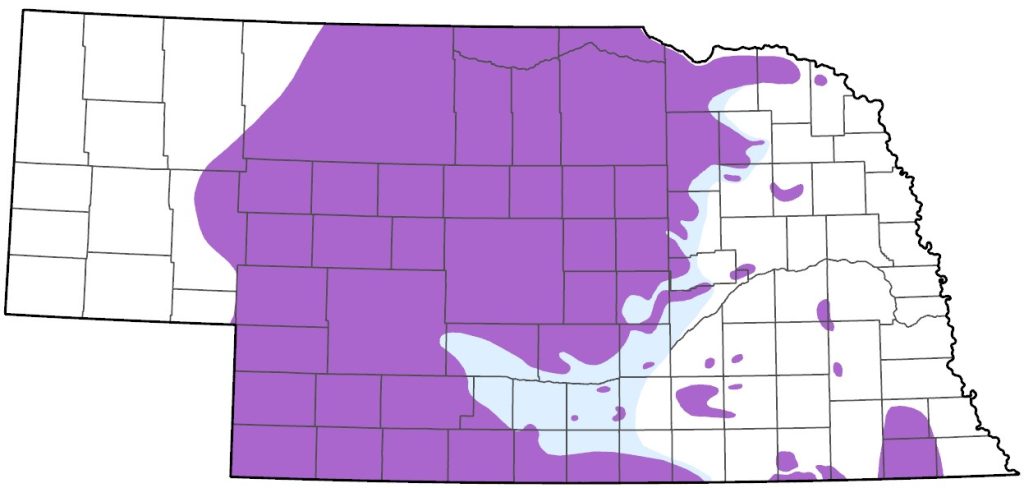

Status: Locally common regular resident central and locally east, rare west. Uncommon casual winter visitor east of breeding range.

Documentation: Specimen: UNSM ZM10301, 25 Nov 1912 Comstock, Custer Co.

Taxonomy: Three subspecies are recognized (AviList 2025, Johnson et al 2020): cupido, the extinct Heath Hen, attwateri, surviving in coastal Texas only with extensive conservation efforts, and pinnatus, the subspecies occurring in Nebraska and the northern Great Plains and Midwest.

Some authors (Johnsgard 1979; Sibley and Monroe 1990) have considered this species and Lesser Prairie-Chicken (T. pallidicinctus) conspecific.

See Sharp-tailed Grouse for discussion of hybrids with that species.

Resident: Highest densities occur in north-central Nebraska, especially eastern parts of the Sandhills, and decline to the east, south and west where the range becomes discontinuous. Isolated portions of the species’ range are generally associated with landscapes of grassland located within regions of intensive row-crop agriculture. Population increases and range expansion observed in southeastern Nebraska in the late 1990s and early 2000s, apparently in response to increased land set aside in the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP; Rodgers and Hoffman 2005, Scott Taylor, NGPC, personal communication), tended to be reversed as grain commodity prices subsequently increased and CRP land returned to row-crop agriculture (Jeffrey Lusk, NGPC personal communication; Berger et al 2023). Nevertheless, since the 1980s, Greater Prairie-Chicken numbers appear to be stable or increasing. BBS trend analysis shows an annual increase of 6.79% (95% C.I.; 2.36, 11.45) during the years 1966-2015 (Sauer et al 2017). Much of this overall statewide trend may be driven by increased numbers in the Sandhills in the 1980s; Greater Prairie-Chickens were mostly absent from the northwestern Sandhills until the 1980s and from the southwest until the 1990s, but populations have increased in both regions (Berger et al 2023). See Comments (below).

High spring (15 Feb-31 Mar) counts are 250 near Mullen, Hooker Co 13 Mar 2011, 160 along North Wagon Trail Road, Lincoln Co 19 Feb 2025, 120 along East Hall School Road, Lincoln Co 22 Feb 2025, and 95 along Road 443, Custer Co 22 Feb 2010.

Ecological relationships between Greater Prairie-Chicken and Sharp-tailed Grouse in the Sandhills were discussed by Berger et al (2023). These authors stated that Greater Prairie-Chicken and Sharp-tailed Grouse “do not behave as a single species in the Sandhills” and Hiller et al (2019) noted that breeding habitat niches were different between the two species although habitat use was similar during the rest of the year and pointed out that shifts in habitat quality could provide an advantage to one or the other species.

In the Panhandle, Greater Prairie-Chicken is expanding westward, although it may occur with some regularity only in extreme eastern Sheridan Co and in and near Crescent Lake NWR in Garden Co. Recent reports from Sheridan Co are of three at Smith Lake WMA 10 Aug 2006, one on a Sharp-tailed Grouse lek in southeast Sheridan Co 20 Apr 2016, three about 20 miles south of Gordon 7 Jun 2016, one at Walgren Lake 20 May 2018, and two “Possible” breeding reports from central Sheridan Co (Mollhoff 2016). Three were about halfway between Merriman and Gordon along Irwin Road in extreme northwestern Cherry Co 16 Oct 2023. In Garden Co, the small populations in the CLNWR area continue, possibly increasing; at known lek sites, 21 were a few miles north of Oshkosh and two were at the Blue Creek Road 81 crossing nearby, and about 10 were heard from two directions at CLNWR, all sightings 3 Apr-11 Jun 2024. In 2025, eight reports from the same general area 3 Apr-13 Jun included best tally of 10. Previous records in this area were of up to three each year 2017-2020 Apr-Jun and Sep; four were at Crescent Lake WMA 10 Apr 2021, one south of there near Blue Creek the same day, and two heard in the same area 9 Jul. Earliest records from CLNWR include 11 Jun 1991, and two “Possible” breeding reports (Mollhoff 2016). The only other Panhandle reports are of two in Cheyenne Co 12 Apr 2011, one in Deuel Co 20 May 2016, two in Deuel Co 1 Sep 2019, three there 6 Sep 2020, one in Morrill Co 4 May 2018, and single “Possible” and “Probable” reports from northeastern Morrill Co (Mollhoff 2016). That expansion is occurring at the western edge of the species’ range is supported by Berger et al (2023).

In northeast Nebraska, there is a long-standing population in central Cedar Co, and small numbers occur as far east as Buckskin Hills WMA, Dixon Co, where at least two leks have been active since at least 2003; peak count there is 24 in 2009. The range also includes most of Antelope Co and extends eastward to southwestern Pierce Co, where 29 were on a lek on 543 Road 2 Apr 2022, northwestern Madison Co to the Battle Creek area, and northwestern Boone Co, where 254 were tallied 29 Dec 2019 (Jason Thiele, personal communication). Adjacent to the east, there are several reports for Stanton and Wayne Cos; singles were in southeastern Wayne Co 5 Apr 2014 and 18 Apr 2019, and one was in Wayne, Wayne Co 19 Nov 2024. There were reports in Stanton Co in 2020 and 2021 in the Elkhorn River Valley; one of 11 near Wood Duck WMA, Stanton Co 3 Apr 2020 was displaying and four were there 8 May, and in 2021 booming was heard there 15 May. Three miles southeast of Stanton, Stanton Co booming was heard 6 May 2021. There were four reports for Stanton Co in 2024, three from 27 Mar-1 May and 18 Oct. Only the second report for Cuming Co were six near Wisner 10 Mar 2024; the only previous report for Cuming Co was 24 Oct 1981, likely a fall wanderer.

Near the Platte River Valley in the northeast, there are several records from an area of sandhills in Nance, Merrick, and extreme southwestern Platte Co, none since 2021. Unexpected was one displaying on a gravel road southwest of Scribner, Dodge Co 17 Apr 2022 (Amanda Johnson, personal communication).

South of the Platte River this species occurs east to Frontier Co and throughout the Republican River Valley; 35 were tallied along Cadams Road, Nuckolls Co 16 Feb 2024. East of Frontier Co and north of the Republican River in the western Rainwater Basin the regular range extends into northern Hall Co, but farther east habitat is localized as isolated sandhills remnants, and distribution is discontinuous. There are three scattered records for Gosper Co: 30 Apr 2015, 20 Mar 2018 (5), and 1 Jan 2019 (3). In Phelps and Kearney Co reports are more numerous; this area is just north of the species’ north-central Kansas range, which is separate from that of the well-known Flint Hills population (Busby and Zimmerman 2001). Recent reports from these two counties are 23 Mar 2024 Funk WPA, Phelps Co, reports for four locations in Kearney Co 17 Mar-3 Apr 2024, and 24 were at an isolated prairie remnant 3 mi south and 0.5 mi east of Kearney’s I-80 exit in Kearney Co 24 Mar 2025. . There six reports for Adams Co; best tally was 25 on 1 Feb 2021 about 25 miles southwest of Hastings.

Jorgensen (2012) presented evidence that this species had been extirpated as a resident in the eastern Rainwater Basin in the 1930s, but since then prairie-chickens have colonized and persisted at isolated grassland tracts, including those on wetland conservation properties where trees and brush have been removed; small numbers have been observed at and around grassland tracts associated with wetland conservation properties. Reduced vertical structure such as trees and farmsteads in the landscape concomitant with agricultural intensification may also have benefitted the species (Jorgensen 2012).

Since 2005, leks have been established at Harvard WPA and Hultine North WPA, both in Clay Co, and in Fillmore Co around Brauning WPA, near Rauscher WPA and at Wilkins WPA; best count at these locations was 22 at Hultine North WPA in 2005 and 2008 and Kissinger Basin WMA, Clay Co, hosted 14 on 30 Oct 2022. In extreme southwest Fillmore Co, 15 were seen along Highway 74 on 9 Apr 2017. The first lek in York Co for many years was at Kirkpatrick Basin South WMA, with two males there 18 May 2007 and two on 12 May 2008; since then, singles were reported there 17 May 2021 and 8 May 2022. One at Marsh Duck WMA, York Co 13 Feb 2017 was the first sighting there. There are four reports for Hamilton Co, most recent 22 Mar 2019, and two for Polk Co, 24 Apr 2005 and 20 Apr 2018. There are three records for Seward Co, all since 2017: singles were at or near Straightwater WMA 2 Jun 2017 and 1 May 2022, south of Utica 8 Nov 2017, and near Tamora 14 Apr 2017 (Dubry-Garcia 2018).

Perhaps related to the establishment of new leks in the eastern Rainwater Basin discussed above was formation of a new lek on Mormon Island, Hall Co in 2015, possibly as a result of “well above average winter temperatures” (Andrew Caven, personal communication), that has continued since with up to 30 males present and all activities of full displays expected at a permanent lek being observed (Caven et al 2018). As the number of males increased, the lek split, forming multiple leks (Andrew Caven, personal communication). Nearby sightings in Apr 2020 and 2021 include a small lek of 5-6 birds on Shoemaker Island, Hall Co in Apr 2020 and 2021 and a few birds lekking in another pasture there (Andrew Caven, personal communication).

The Mormon Island lek discussed above was occupied by males beginning 30 Jan in 2015, more than one month prior to the typical start of the lekking season in Nebraska and what has generally been published for the central Great Plains (Caven et al 2018). Further, consistent lek attendance for both sexes, as well as male display behavior, was extended, compared with published data, through 13 May in 2015 (Caven et al 2018). This early and extended lekking season may be a consequence of extended periods of mild winters; it is possible that warming trends may alter the lekking phenology of Greater Prairie-Chickens with unknown impacts (Caven et al 2018).

In the southeast, as of spring 2017, there were four disjunct areas in several southeastern counties where native grasslands persist or have been planted to grassland under the CRP (Mollhoff 2016): (1) Jefferson and southwestern Gage, (2) eastern Gage, Johnson, Pawnee, and Richardson, (3) southeastern Butler and adjacent portions of Saunders and Lancaster, and (4) southwestern Lancaster. The populations in these areas may represent the northern range extent of the larger populations present in the Kansas Flint Hills. Recent reports from Jefferson Co are few and include booming heard at Rock Glen WMA 8 May 2012. The single record for Thayer Co is of three on 6 Mar 2015. The center of the southeasternmost population is Pawnee Co, where numbers peaked at 41 on a long-standing booming ground at Burchard WMA 7-9 Apr 2017. In recent years small numbers have occurred in extreme southeastern Butler Co; two leks with a total of 15+ birds were found 10 Apr 2010, and as many as 15 were on a lek at 25th and U Roads 10 Apr 2016; reports continue at this lek, best tally 25 (Joseph Gubanyi, personal communication). A survey of six previously known lek sites in southeastern Butler Co 13 Apr 2019 by Joseph Gubanyi found two occupied by an overall total of at least 18 birds. Apparently only the second record from the Branched Oak Lake area in Lancaster Co was of booming heard “to the southwest” 3 May 2024; previously three were reported north of the lake 30 Sep 2016. There is a population at Audubon Spring Creek Prairie and neighboring private grasslands south of Denton, Lancaster Co; as many as 17 have been seen since 2000, those on 8 Oct 2002, and breeding was documented there in 2002, 2003, and 2010. An apparent stray was at Pioneers Park, Lancaster Co 18 Aug 2024.

The only recent report in the southeast away from these disjunct populations is of a lek with four birds in southern Cass Co at the junction of Highways 50 and 34 on 13 Apr 2006 and, more recently, one was seen 3 mi west and 0.5 mi north of this junction 3 Jan 2020 (Josiah Dallmann, personal communication).

Although generally thought to undergo only local movements except on occasion in winter (Johnson et al 2020; see Winter), a recent telemetry study (Vogel et al 2015) found that a female that had been translocated from Chase Co, Nebraska to Grand River Grasslands, Ringgold Co, Iowa, subsequently travelled 3988 km into parts of four neighboring states 5 Apr 2013- 20 Jun 2014. The longest daily movements occurred in the spring periods during this period. It was suggested (Vogel et al 2015) that translocated birds move greater distances than local birds, probably due to unfavorable social interactions between lekking females and searching for mates at different lek sites.

- Breeding Phenology:

Lek activity: 7 Feb-20 Jun. Peak around 10 Apr. See discussion above.

Eggs: 19 Apr (Mollhoff 2022)-12 Jul (latter date may represent re-nesting). - Dependent young: 10 Jun-29 Jul.

Winter: This species has a propensity to move southeastward during severe winters, although as habitat has become fragmented throughout the range, this propensity has declined (Johnson et al 2020). In Nebraska, such movements have not been observed since winter 1983-1984, when there was an influx into Polk Co mid-Dec through 9 Jan, including a flock of 100 on the York-Polk Co line three miles from Benedict (Morris 1984). A large flock of 37 was at Mormon Island Crane Meadows, Hall Co 14 Feb 2018; this location is not far south of the nearest breeding locations in northwestern Hall Co and adjacent Buffalo Co and suggests at least occasional winter visits to the Crane Meadows.

The role and possible effects of winter movements as they relate to the history of Greater Prairie-Chicken in Iowa was discussed by Dinsmore and Dinsmore (2020).

- High counts: (non CBC) 500+ in Wheeler Co 3 Jan 2016, 160+ (one flock) North Wagon Trail Road, Lincoln Co 19 Feb 2025, 150+ (in one flock) Boone Co 29 Dec 2018, and 135 (in one flock) near Brady, Lincoln Co 1 Jan 2017.

Comments: It is not at all clear what the pre-settlement distribution of Greater Prairie-Chicken was in Nebraska but judging from habitat requirements and early accounts from Iowa and Illinois (Bent 1932), it is likely the species was present at least in the mid- and tall-grass prairies of extreme eastern Nebraska. The most popular theory explaining the changing distribution of this species in Nebraska over the past 150 years is referred to as “follow the plow”, which is based on the progression of European settlement westward beginning in the 1850s that mixed croplands with grasslands resulting in a consequential dramatic increase in Greater Prairie-Chicken numbers, a phenomenon experienced earlier and described by pioneers in Illinois and Iowa (Bent 1932). An alternative theory to “follow the plow” was suggested by genetic studies by Ross et al (2006) that suggested the rate of range expansion and associated population increases supposedly observed as settler farmers moved westward in reality would have far exceeded the reproductive capability of Greater Prairie-Chicken given the relatively short period of European settlement. Ross et al (2006), based on their genetic data, suggested that Greater Prairie-Chickens had in fact been present since the emergence of extensive northern prairies following the Last Glacial Maximum around 9000 years ago. Perhaps replacement of prairie with cropland resulted in greater visibility of the prairie-chickens that had in fact been present for millennia (J. Augustine, personal communication).

Numbers decreased in at least eastern Nebraska during the 20th Century as tallgrass prairie was almost completely converted to croplands. Since the 1980s however, there has been a general increase in the Greater Prairie-Chicken’s range and numbers in eastern Nebraska, possibly as a consequence of the increasingly mosaic nature of agricultural areas there as CRP fields and smaller farms with pastures such as “hobby” farms became more widespread (Thomas Labedz, personal communication). Two were in southeastern Washington Co 26 Aug 2010 and one flushed from a Dodge Co cornfield 2 Apr 2010 was the observers’ first for the county.

It is likely that numbers in Nebraska peaked in the 1880s. Two hunting parties based in Omaha shot 422 and 287 prairie-chickens 6 Sep 1865, and in 1874-1875 shipments of birds to markets in New York and Boston totaled at least 100,000 (Swenk 1936).

Since about 2004 there have been increasing observations of leks in row-crop fields rather than the usual grasslands in counties where there had been no recent reports of the species. Reports in 2004 were of a group of 10-15 males in a cornfield adjacent to grassland in Lincoln Co 17 Mar, 16 birds, including a female, in a central Fillmore Co cornfield with no nearby grasslands 24 May, and 30-35 birds in a wheat field planted to corn in Franklin Co 23 Mar; there was a report from northwest Nuckolls Co in 2007. Unusual was a group displaying in a corn stubble field at 25th and U roads in Butler Co 4-6 Apr 2023.

Images

Abbreviations

CBC: Christmas Bird Count

CRP: Conservation Reserve Program

BBS: Breeding Bird Survey

NGPC: Nebraska Game and Parks Commission

NWR: National Wildlife Refuge

UNSM: University of Nebraska State Museum

WMA: Wildlife Management Area (state)

WPA: Waterfowl Production Area (federal)

Acknowledgement

Jeffrey J. Lusk provided numerous helpful comments that improved this species account.

Literature Cited

AviList Core Team, 2025. AviList: The Global Avian Checklist, v2025. https://doi.org/10.2173/avilist.v2025.

Bent, A.C. 1932. Life histories of North American gallinaceous birds. Bulletin of the United State National Museum 162. Dover Publications Reprint 1963, New York, New York, USA.

Berger, D.J., J.J. Lusk, L.A. Powell, and J.P. Carroll. 2023. Exploring Old Data with New Tricks: Long-Term Monitoring Indicates Spatial and Temporal Changes in Populations of Sympatric Prairie Grouse in the Nebraska Sandhills. Diversity 15, 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/d15010114.

Busby, W.H., and J.L. Zimmerman. 2001. Kansas Breeding Bird Atlas. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas, USA.

Caven, A.J., K.C. King, E.M. Brinley Buckley, G.D. Wright, N. Arcilla, and R.P. McLean. 2018. Sustained early Interior Greater Prairie-chicken (Tympanuchus cupido pinnatus) lekking behavior at lek in central Nebraska. Kansas Ornithological Society Bulletin 69: 29-40.

Dinsmore, J.J., and S.J. Dinsmore. 2020. Greater Prairie-Chickens in Iowa: Another Look. Iowa Bird Life 90: 61-68

Dubry-Garcia, L. 2018. Greater Prairie-Chicken photos, Bird Nerds of Nebraska Facebook page, 14 April 2018.

Hiller, T.L.; McFadden, J.E.; Powell, L.A.; Schacht, W.H. 2019. Seasonal and Interspecific Landscape Use of Sympatric Greater Prairie-Chickens and Plains Sharp-Tailed Grouse. Wildlife Society Bull. 43, 244–255.

Johnsgard, P.A. 1979. Birds of the Great Plains: breeding species and their distribution. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA.

Johnson, J.A., M.A. Schroeder, and L.A. Robb. 2020. Greater Prairie-Chicken (Tympanuchus cupido), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.grpchi.01.

Jorgensen, J.G. 2012. Birds of the Rainwater Basin, Nebraska. Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA.

Mollhoff, W.J. 2016. The Second Nebraska Breeding Bird Atlas. Bull. Univ. Nebraska State Museum Vol 29. University of Nebraska State Museum, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA.

Mollhoff, W.J. 2022. Nest records of Nebraska birds. Nebraska Ornithologists’ Union Occasional Paper Number 9.

Morris, L. 1984. York Co. NBR 52: 23.

Rodgers, R.D., and RW. Hoffman. 2005. Prairie grouse response to Conservation Reserve Grasslands: an overview. The Conservation Reserve Program – Planting for the Future: Proceedings of a National Conference, ed. A.W. Allen and M.W. Vandever, 120-28. USGS, Biological Resources Division Scientific Investigation Report 2005-5145.

Ross, J.D., A.D. Arndt, R.F.C. Smith, J.A. Johnson, and J.L. Bouzat. 2006. Re-examination of the historical range of the greater prairie chicken using provenance data and DNA analysis of museum collections. Conservation Genetics 7:735–750. DOI 10.1007/s10592-005-9110-9.

Sauer, J.R., D.K. Niven, J.E. Hines, D.J. Ziolkowski, Jr, K.L. Pardieck, J.E. Fallon, and W.A. Link. 2017. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 – 2015 (Nebraska). Version 2.07. USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, Maryland, USA.

Sibley, C.G., and B.L. Monroe, Jr. 1990. Distribution and taxonomy of birds of the world. Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

Swenk, M.H. 1936. Editorial Page. NBR 4: 11-12.

Vogel, J.A., S.E. Shepherd, and D.M. Debinski. 2015. An Unexpected Journey: Greater Prairie-chicken Travels Nearly 4000 km after Translocation to Iowa. American Midland Naturalist 174: 343-349.

Recommended Citation

Silcock, W.R., and J.G. Jorgensen. 2025. Greater Prairie-Chicken (Tympanuchus cupido). In Birds of Nebraska — Online. www.BirdsofNebraska.org

Birds of Nebraska – Online

Updated 3 Sep 2025, map updated 21 Jun 2021