Colaptes auratus auratus, C. A. LUTEUS, C. a. COLLARIS (cANESCENS)

Status:

“yellow-shafted flicker”: Common spring and fall migrant east and central, uncommon west. Common breeder east and central, uncommon west (Pine Ridge, North and South Platte river valleys). Fairly common winter visitor east and central, uncommon west.

“red-shafted flicker”: Common winter visitor (altitudinal movement from Rocky Mountains) west and west central, uncommon east central, rare east. Rare casual summer visitor west.

“red-shafted flicker”/”yellow-shafted flicker” (intergrade/introgressant): Common breeder west, rare casual elsewhere. Common spring and fall migrant and winter visitor west and central, uncommon east.

Movements of each of these phenotypes are discussed separately below.

Documentation: Specimen: UNSM ZM6281, 6 Jul 1892 Lincoln, Lancaster Co.

Taxonomy: Nine subspecies are recognized (AviList 2025, Wiebe and Moore 2024), five north of Mexico. The five northern subspecies are separated into two subspecies groups, “red-shafted” and “yellow-shafted”. The three “red-shafted” subspecies are cafer of coastal Alaska to northern California, collaris of the Pacific Slope from California south and the Rocky Mountains from southwestern Saskatchewan south to Texas, and nanus of west Texas to northeast Mexico. Subspecies canescens has been recognized as separable from collaris by some authors; it occupies the Rocky Mountains part of the range given above for collaris, and we use the name canescens below for clarification. The “yellow-shafted” group consists of luteus from central Alaska east across Canada to southern Labrador and Newfoundland, and south to Montana and the northeastern United States, and auratus of the southeastern United States, south of luteus, and west to eastern North and South Dakota, the eastern half of Nebraska, most of Kansas and Oklahoma, and eastern Texas east to Virginia and Florida.

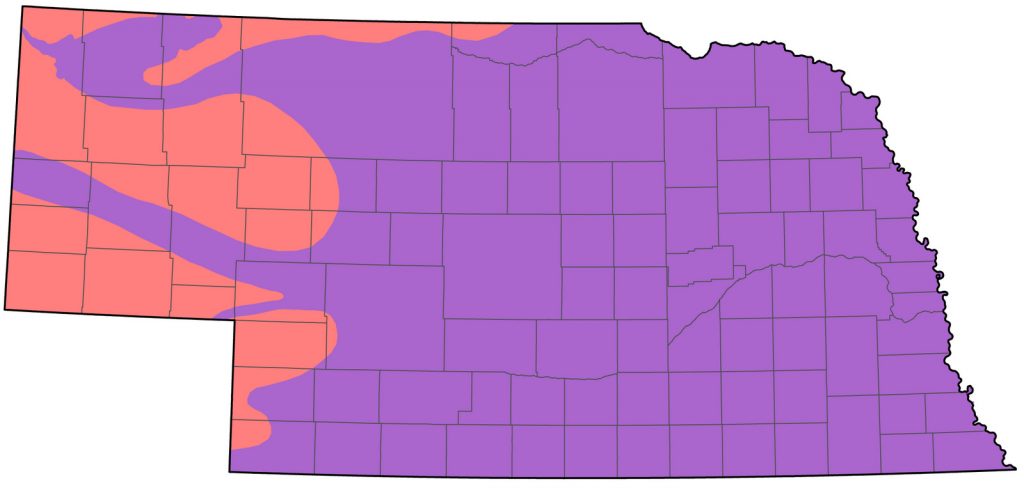

West of the range of auratus is a wide intergradation zone where “yellow-shafted” auratus and “red-shafted” canescens meet. There are probably no “pure” canescens in Nebraska in summer (Short 1961), and possibly only very few “pure” auratus in extreme eastern Nebraska, with most summer birds being intergrades (Short 1961). Few parental types occur within the rather wide intergradation zone, where mating has been considered random (Sibley and Monroe 1990). Recent genomic studies, however, have found that phenotypic color differences in flickers are affected by an extremely small number of locations in the genome, undetectable by less sensitive methods, that might provide a basis for some level of assortative mating (Aguillon et al 2018, Aguillon et al 2021).

The center of the intergradation zone, which had been considered stable in position and width since the late 19th century (Moore and Buchanan 1985) and relatively young, only 4000-7500 years (Wiebe and Moore 2024), passed from the Black Hills of South Dakota southward through Chadron to near Crook in northeast Colorado (Short 1961). This placed the zone roughly along a north-south line in the center of the Nebraska Panhandle in the early 1980s (Moore and Buchanan 1985). A recent study, however, detected rapid movement (ca. 2.1 km/year) of the hybrid zone within the 35+/- years since the early 1980s westward about 60 mi (73 km) (Aguillon and Rohwer 2021) to align approximately with the Wyoming-Nebraska boundary. The hybrid zone has not changed in width, however (Aguillon and Rohwer 2021, Moore and Buchanan 1985). There was no detectable genetically driven basis to explain the shift in the hybrid zone, although there is probably a minimal level of assortative mating within the zone (Aguillon and Rohwer 2021, Moore 1987). Aguillon and Rohwer (2021) suggested, therefore, that the hybrid zone shift may be tied instead to changes in the environment (land management and/or climate changes). Correlation of the position and width of the hybrid zone with ecological variables had been suggested by Moore and Price (1993), in particular the transition from ecological communities characteristic of the wetter East to the drier West. Swenson (2006) showed that environmental factors affected the position of Great Plains hybrid zones.

In winter, most birds in western Nebraska are at least “salmon-colored” (Rosche 1994), with some occurring east to the Missouri River; perhaps some fairly pure canescens appear also in the west (Andrews and Righter 1992), although all collected Nebraska specimens are intergrades (Rapp et al 1958). Most migrants and wintering birds are northern “yellow-shafted” birds (auratus and luteus) that show very little intermediate character (Andrews and Righter 1992). Two birds labeled borealis (=luteus) in the Hastings Municipal Museum (HMM 26960) were collected in Adams Co 9 Feb 1951.

The status of flickers in Nebraska relating to eBird submissions was summarized by Jorgensen and Silcock (2020).

An interesting phenomenon occurring in several species, including Northern Flicker far east of the known hybrid zone, is reddening of primarily yellow feathers due to rhodoxanthin, “a rare carotenoid pigment of deep red hue” (Hudon and Mulvihill 2017). There is no apparent genetic cause of this increase in red pigment, but it is attributed to ingestion of the berries of two exotic shrubs, one of which, Tatarian honeysuckle (Lonicera tatarica), occurs in Nebraska (Hudon and Mulvihill 2017, Thomas Labedz, personal communication). In Nebraska this effect would be difficult to discern in winter as Northern (Red-shafted) Flickers occur over most of the state at that time, but any summer report of such birds might be attributable to Tatarian honeysuckle berry ingestion.

“YELLOW-SHAFTED FLICKER” (luteus, auratus)

Resident: According to Wiebe and Moore (2024), “Birds that breed north of 37–38°N migrate to wintering grounds in se. U.S.; birds south of this latitude appear to be more or less resident.” Thus, since Nebraska lies entirely north of “37-38”, breeders in the state generally will be expected to leave the state during winter, although a few may attempt to overwinter in mild conditions. Bent (1939) cited notes by a Dr. Paul L. Errington on the winter-killing of flickers in central Iowa, that involved a study of the droppings of the three birds that he studied during winter; “it appeared that they were much weakened by improper food, too large a proportion of indigestible seeds, mainly those of the sumac, and not enough animal food, which ordinarily amounts to more than half of the average food supply.”

Spring: Mar 19, 19, 20 <<<>>> May 4, 6, 6 (west)

Earlier and later dates in the west are presumed winter or summer residents, respectively.

Peak migration of “yellow-shafted flickers” in the east and central occurs in late Mar-early Apr, but dates are difficult to determine due to wintering birds. There is a detectable increase in eBird reports in the east and central in mid-Mar and numbers are fairly constant through summer, suggesting replacement of wintering birds by summering birds.

In the west, movement is detectable as scattered winter distribution gives way to localized summer distribution on the Pine Ridge and along the Platte river valleys. This changeover occurs during Apr (see dates above).

Most migrating flickers in Nebraska are “yellow-shafted” birds of the subspecies luteus breeding in Canada and the northern US.

- High counts: 50 at Fort Kearny SRA, Buffalo Co 15 May 2018, 40-50 in Lincoln Co 27 Mar 2004, 42 at Lincoln Saline Wetlands Nature Park, Lancaster Co 13 Apr 2018, and 40 at Fort Kearny SRA, 19 Apr 2001.

Summer: Breeding “yellow-shafted” flickers occur statewide, although numbers are much lower in the Panhandle, where mostly limited to the Pine Ridge (Rosche 1982) and the North and South Platte river valleys, but absent over large areas of the Sandhills where suitable habitat is restricted.

- Breeding Phenology

Copulation: 1 Apr-13 May

Nest building: 16 Apr-10 May

Eggs: 31 Mar- 1 Jul (Mollhoff 2022)

Nestlings: 23 May-20 Jun

Fledglings: 23 Apr-22 Jul

Fall: Aug 28, 29, 31 <<<>>> winter (west)

Peak migration occurs in during early Sep and Oct in the east and central where migrants may not be readily identified amongst local breeders, however passage of migrant “yellow-shafted” birds in the Panhandle is more easily discernible since there are fewer summering birds and occurs mostly during Sep.

As in spring, northern “yellow-shafted” breeders from Canada and states north of Nebraska are conspicuous migrants. Most migrant “yellow-shafted” flickers migrate through eastern Nebraska (see below); as Wiebe and Moore (2024) state: “banding recovery records show that northern populations of Yellow-shafted Flickers are strongly migratory, funneling into se. U.S. in late autumn”.

- High counts: 270 over Omaha, Douglas Co 7 Oct 2015 (flew over for five hours), 73 at Lake McConaughy, Keith Co 12 Oct 2000 (47 “red-shafted”, 9 “yellow-shafted”, 17 intermediate), 50+ at Red Willow Reservoir, Frontier Co 3 Oct 1998, 50 in Garfield Co 7 Sep 2015, and 49 at Oliver Reservoir, Kimball Co 11 Oct 2000 (41 “red-shafted, 2 “yellow-shafted”, 6 intermediate).

Winter: CBC data indicate a generally even winter distribution of flickers statewide, with somewhat lower numbers in the north and west.

“RED-SHAFTED FLICKER” (canescens)

Winter: Aug 30, 31, 31 <<<>>> May 30, 30, 31 (west and west central); Sep 18, 18, 19 <<<>>> Apr 16, 17, 17 (east central and east)

Earlier dates in the east central and east are 2 Sep 2017 Sarpy Co, 9 Sep 2020 Antelope Co, and 15 Sep 2012 Sarpy Co.

Later dates in the east-central and east are 23-24 Apr 2015 (six in seven miles on 23 Apr) Douglas Co, 26 Apr 2020 Antelope Co, 3 May 2008 Knox Co, 13 May 2017 Hall Co, 16 May 2017 Brown Co, 17 May 2006 Cedar Co, 17 May 2017 Buffalo Co, 25 May 2016 northeast Cherry Co, 2 Jun 2017 Rock Co, 4 Jun 2023 Holt Co, and two on 6 Jun 2017 in Brown Co.

The above dates are for birds with red shafts; later dates in the east without details are most likely paler shades, often referred to as “salmon-shafted”.

There is a significant eastward movement of “red-shafted flickers” in fall, apparently a continuation of altitudinal movement out of the mountains (Bent 1939), and another example of “altitudinal” migration in Nebraska (see Mountain Bluebird).

Peak numbers of “red-shafted flickers” occur in Oct; 49 flickers counted at Oliver Reservoir, Kimball Co 11 Oct 2000 included 41 “red-shafted, 2 “yellow-shafted”, and 6 intermediates. In spring a high count of “red-shafted” flickers was 10 at Potmesil Ranch, Sheridan Co 10 Apr 2009.

The distribution of “red-shafted flickers” on CBCs is strongly biased to the west; recent CBC data show that almost all flickers in the west are “red-shafted” or intermediate, and in the east only about 3% are “red-shafted”.

Summer: There are five records of phenotypic “red-shafted flicker”, all at the Pine Ridge:

13 Jun 2024 East Ash Canyon, Dawes Co

18 Jun 2019 Dawes Co

20 Jun 2020 Smiley Canyon, Sioux Co

21 Jun 2016 Morrill Co

22 Jun 2024 Walgren Lake, Sheridan Co.

“Red-shafted flickers” do not breed in South Dakota or Kansas (Tallman et al 2002; Thompson et al 2011). In South Dakota, no pure “red-shafted flickers” were found among 511 breeding specimens collected mostly in western South Dakota (Tallman et al 2002). Although there are numerous late May- early Aug Nebraska reports of “red-shafted” flickers in the west-central and Panhandle, few have details, and it is likely that most of these summer reports are of intergrades showing near-red shafts.

“INTERGRADE (SALMON-SHAFTED) FLICKER” (auratus x canescens)

Spring: winter <<<>>> Jun 22, 24, 25 (east and central)

For later dates see Summer.

Maps in eBird (eBird.org) indicate a concentration of wintering “intergrade flickers” in Kansas that dissipates in Apr as birds move north and west through Nebraska. Arrival dates in for such spring migrants are difficult to determine due to wintering birds in Nebraska.

Summer: Records for late Jun through mid-Sep are numerous only in the Panhandle. In the central and east, there are only 17 records 26 Jun-13 Sep, two of these in the east, 11 Aug 2024 (2) Cuming Co, and 11 Aug 2024 Nance Co.

Fall: Sep 21, 21, 21 <<<>>> winter (central and east)

Earlier dates central and east are 14 Sep 2024 Nuckolls Co, and 18 Sep 2023 Lancaster Co.

According to Wiebe and Moore (2024), “Breeders from … n. Great Plains (to include most of the northern hybrid-zone populations) migrate south-southeast, predominantly into e. Texas and Oklahoma.” Thus, “intergrade flickers” in Nebraska in fall reflect an influx of migrants from further north in the hybrid zone supplemented by “intergrade flickers” from further west. Maps in eBird indicate a concentration of wintering “intergrade flickers” in Kansas that builds up in Sep as birds move south and east through Nebraska. Departure dates for such fall migrants are difficult to determine due to wintering birds in Nebraska.

Winter: The distribution of “intergrade flickers” in winter across Nebraska resembles that of “red-shafted flickers”, with numbers declining eastward.

Images

Abbreviations

CBC: Christmas Bird Count

HMM: Hastings Municipal Museum

SRA: State Recreation Area

UNSM: University of Nebraska State Museum

Acknowledgement

Photograph (top) of a Northern Flicker at Papillion, Sarpy Co 13 Sep 2012 by Phil Swanson.

Literature Cited

Aguillon, S.M., L. Campagna, R.G. Harrison, and I.J. Lovette. 2018. A flicker of hope: Genomic data distinguish Northern Flicker taxa despite low levels of divergence. Auk 135: 748-766. https://doi.org/10.1642/AUK-18-7.1.

Aguillon, S.M., and V.G. Rohwer. 2021. Revisiting a classic hybrid zone: rapid movement of the northern flicker hybrid zone in contemporary times. bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.16.456504.

Aguillon, S.M, J. Walsh, and I.J. Lovette. 2021. Extensive hybridization reveals multiple coloration genes underlying a complex plumage phenotype. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2020.1805

Andrews, R., and R. Righter. 1992. Colorado birds. Denver Museum of Natural History, Denver, Colorado, USA.

AviList Core Team, 2025. AviList: The Global Avian Checklist, v2025. https://doi.org/10.2173/avilist.v2025.

Bent, A.C. 1939. Life histories of North American woodpeckers. Bulletin of the United States National Museum 174. Dover Publications Reprint 1964, New York, New York, USA.

Hudon, J., and R. Mulvihill. 2017. Diet-induced Plumage Erythrism as a Result of the Spread of Alien Shrubs

in North America. North American Bird Bander 42: 95-103.

Jorgensen, J.G, and W. R. Silcock. 2020. Yellow-shafted, Red-shafted and intergrade flickers in Nebraska. News & updates Archives – Birds of Nebraska – Online (outdoornebraska.gov)

Mollhoff, W.J. 2022. Nest records of Nebraska birds. Nebraska Ornithologists’ Union Occasional Paper Number 9.

Moore, W.S. 1987. Random mating in the Northern Flicker hybrid zone: implications for the evolution of bright and contrasting plumage patterns in birds. Evolution 41: 539-546.

Moore, W.S., and D.B. Buchanan. 1985. Stability of the Northern Flicker hybrid zone. Evolution 39:135-151.

Moore, W.S., and J.T. Price. 1993. The nature of selection in the northern flicker hybrid 409 zone and its implications for speciation theory. Pp. 196–225 in R. G. Harrison, 410 ed. Hybrid Zones and the Evolutionary Process. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 411 UK.

Rapp, W.F. Jr., J.L.C. Rapp, H.E. Baumgarten, and R.A. Moser. 1958. Revised checklist of Nebraska birds. Occasional Papers 5, Nebraska Ornithologists’ Union, Crete, Nebraska, USA.

Rosche, R.C. 1982. Birds of northwestern Nebraska and southwestern South Dakota, an annotated checklist. Cottonwood Press, Crawford, Nebraska, USA.

Rosche, R.C. 1994. Birds of the Lake McConaughy area and the North Platte River valley, Nebraska. Published by the author, Chadron, Nebraska, USA.

Short, L.L., Jr. 1961. Notes on bird distribution in the central Plains. NBR 29: 2-22.

Sibley, C.G., and B.L. Monroe, Jr. 1990. Distribution and taxonomy of birds of the world. Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut, USA and London, England.

Swenson, N. G. 2006. Gis-based niche models reveal unifying climatic mechanisms that maintain the location of avian hybrid zones in a North American suture zone. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 19: 717–25.

Tallman, D.A., Swanson, D.L., and J.S. Palmer. 2002. Birds of South Dakota. Midstates/Quality Quick Print, Aberdeen, South Dakota, USA.

Thompson, M.C., C.A. Ely, B. Gress, C. Otte, S.T. Patti, D. Seibel, and E.A. Young. 2011. Birds of Kansas. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas, USA.

Wiebe, K.L., and W.S. Moore. 2024. Northern Flicker (Colaptes auratus), version 2.1. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald and B. K. Keeney, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.norfli.02.1.

Recommended Citation

Silcock, W.R., and J.G. Jorgensen. 2025. Northern Flicker (Colaptes auratus ). In Birds of Nebraska — Online. www.BirdsofNebraska.org

Birds of Nebraska – Online

Updated 17 Jul 2025