Falco peregrinus anatum, F. p. tundrius

Status: Uncommon regular spring and fall migrant statewide. Locally uncommon regular resident east, extirpated west. Rare casual winter visitor statewide.

Documentation: Specimens: UNSM ZM7696 (anatum) 14 May 1915 Garden Co; UNSM ZM7695 (tundrius) 5 May 1935 near Stapleton, Logan Co.

Taxonomy: There are 18 subspecies recognized world-wide (AviList 2025), three of which occur in North America: tundrius, breeding from Alaska to Greenland, pealei from the Aleutians to southern Alaska and southwest Canada, and anatum, in North America south of the tundra to northern Mexico.

Although earlier published information (Bruner et al 1904, Rapp et al 1958) suggested that only the widespread subspecies anatum has been found in Nebraska, the paler northern subspecies tundrius occurs also. There are three specimens of tundrius in the UNSM collection. An immature tundrius was in Phelps Co 2 Sep 2002, an emaciated tundrius was picked up and photographed in Buffalo Co 22 Jun 2013, and in the Rainwater Basin tundrius is predominant in migration, with only a small number of observations of anatum (Jorgensen 2012). Tundrius would be expected to occur in migration in Nebraska (Palmer 1988); it is the commonest of the subspecies occurring in Missouri during migration (Robbins 2018).

Captive stock used in introductions at temperate latitudes in eastern and central North America involved several subspecies, including all three North American and at least two European subspecies (Tordoff and Redig 2001). The genetic heritage of individuals used in hacking efforts in Omaha in the 1980s and 1990s is uncertain. Populations in the Midwest are now established, introductions have essentially ceased, and dispersal by young birds that subsequently breed away from natal sites has resulted in a population that has an amalgamated genetic composition (Tordoff and Redig 2001). Although anatum genes dominate in this population, there are likely no pure anatum occurring or breeding in Nebraska (Tordoff and Redig 2001). The presence of an immature resembling the dark, heavily streaked west coast subspecies pealei in Dakota Co 15 Aug 2014 was thought by the observer to result from the reintroduction efforts in eastern North America.

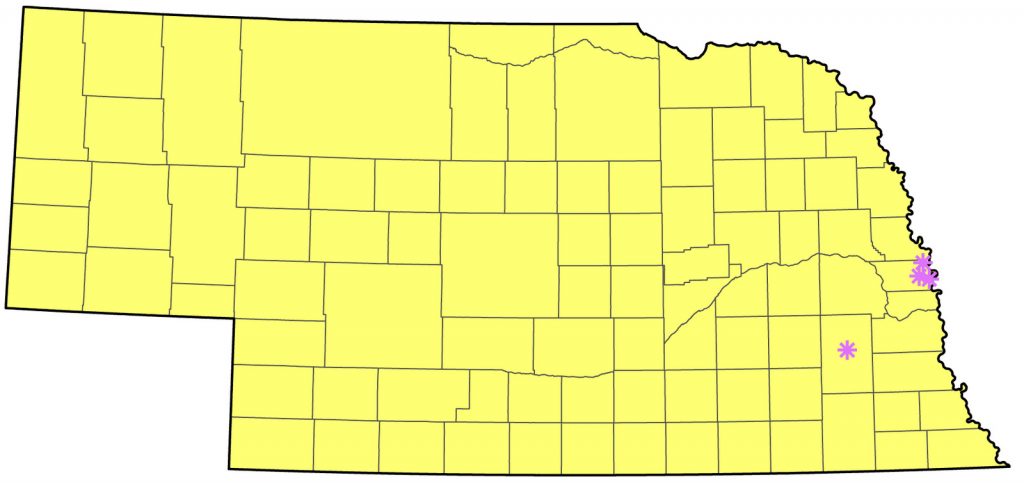

Resident: Resident birds in Nebraska descend from birds reintroduced to the Midwest, beginning with hacking efforts in Omaha during the 1980s. As of 2021, there are four known breeding locations, three in Omaha and one in Lincoln (see Nebraska-Peregrine-Falcon-pairs-and-productivity-by-year_2022 for more information). Most winters, at least one adult is observed in the vicinity of the nest sites.

Efforts under the auspices of the Nebraska Peregrine Falcon Project, a partnership of Audubon Society of Omaha, Fontenelle Forest Association, Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, and Raptor Recovery Center, to establish breeding birds in Omaha began in 1988 when six young birds provided by the Raptor Center at the University of Minnesota were hacked at the WoodmenLife Tower, 18th and Farnam (Cortelyou 1988, Ducey 2008). Two died, and the others departed in fall, the last bird in early Oct. The first modern Nebraska nesting was at the WoodmenLife Tower in 1992, when a male named Woody from the 1988 release, who had returned alone each year since his hacking, returned in 1992 with a female named Windy who had been released in Des Moines, Iowa in 1991 (Morris 1992). This pair fledged three young that hatched 11-13 Jun. Nesting has taken place at the WoodmenLife Tower each year since, involving at least two successful pairings of a bird fledged in Omaha with birds released from other locations (for example, see Winter).

The Mutual of Omaha building at 33rd and Farnam was also used as a hack site in the late 1980s, but there had been no subsequent nesting activity there until 2017. The male, Orozco, was hatched at the Nebraska State Capitol in 2015 and the female, Chayton, was hatched in Kansas City, Missouri, in 2014. The pair laid two eggs, which hatched, but the eyases died. However, in 2018 Chayton departed and paired with Mintaka at the WoodmenLife Tower in Omaha. Nesting was successful in 2019-2021 with four young fledged each year, presumably with parents Orozco and Sierra.

In 2015, nesting was confirmed at the Omaha Public Power District’s North Omaha Power Station where a nest box had been placed on a smokestack several years before. The female of this pair, Clark, hatched at the Nebraska State Capitol in 2012, but had been assumed to be a male due to a banding glitch. The male was unidentified. Nesting also occurred at this location in 2016, copulation was observed 17 Feb 2017, and one was there 12 Apr 2018 but had been “hard to find this spring” (Jerry Toll, personal communication); nesting was successful in 2019 with three young fledged, although Clark was not the female in this pair (Jerry Toll, personal communication). Leading into the 2020 season, a new pair attempted to occupy the site, each with auxiliary bands that are colored black over blue (Jerry Toll, personal communication); the female’s alphanumeric code indicated she was banded 26 May 2016 at the Kansas City Power and Lite IATAN generating station smokestack and named Sierra (Jerry Toll, personal communication). Clark arrived soon after, however, and took over the box from Sierra 21 Feb and paired with Cheveyo, another Kansas City bird, but he was soon replaced on 2 Mar by another male whose bands show he is the 2012 nest mate of Clark appropriately named Lewis. Lewis and Clark settled down, copulated twice, and as of 21 Mar appear ready to settle in (Jerry Toll, personal communication). Three eggs were laid around 30 Mar 2020, and the first of three chicks hatched 3 May. Four young were fledged. In 2021, Lewis and Clark had four chicks that were banded in late May (Jerry Toll, personal communication). Eggs hatched 11 May 2022.

As Midwest Peregrine Falcon populations increased due to hacking efforts, birds eventually colonized the Nebraska State Capitol in Lincoln. A banded male that had been released in Omaha in 1989 frequented the area in the summer of 1990; pairs were present most years through 2002, and in 2003 a pair of young birds began nesting in Apr. The female, only a yearling, fledged in Minneapolis in 2002 and the male, 19/K, in Des Moines in 2001. Two eggs were present 21 May, but they did not hatch. In 2005, a pair which included the same male, 19/K, and a female, Ally, hatched in Winnipeg, Manitoba in 2004, successfully fledged one bird. From 2005-2018, this same pair has nested each year and has fledged 26 young during this period despite varying success, with age possibly being a factor in their unsuccessful nestings in 2015, 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020 (NGPC, unpublished data). Neither adult returned in 2021, the male 19K probably dying and the female Ally was found with a broken leg near Valparaiso, Lancaster Co and rehabilitated but will not be released. Good news was incubation under way at the Capitol Building in Lincoln, Lancaster Co 3 May 2024, presumably by a new pair.

Omaha Public Power Division established a new nest site in May 2024 at its Nebraska City station.

Away from Omaha and Lincoln, two birds were apparently defending a cell tower in Norfolk, Madison Co against a Turkey Vulture 29 Apr 2016 and were still present there and at a similar nearby tower 11 May. No additional observations have been made to suggest nesting is occurring at this site (Scott Buss, personal communication).

A nest box in Topeka, Kansas was occupied in spring 2011 by a pair of Nebraska State Capitol products, the first recorded away from Lincoln. The pair included Boreas, a male fledged in 2007, and Nemaha, a female fledged in 2009.

- Breeding Phenology:

Copulation: 17 Feb-2 Jun

Eggs: 21 Mar-21 May

Nestlings: 3 May- 7 Jul

Fledglings: 17 Jun- 14 Aug

Spring: Mar 13, 13, 15 <<<>>> May 29, 31, 31

Early and late dates above do not include reports from Douglas and Sarpy Cos since 1992 and Lancaster Co since 2003, when breeding birds became established and are resident. Earlier dates away from counties where the species is resident may be of wintering birds (see Winter), although some are likely misidentifications of Prairie Falcon.

Later dates are 3 Jun 2001 eastern Rainwater Basin (Jorgensen 2012), 5 Jun 2005 Harvard WPA, Clay Co, 7 Jun 1922 Omaha, Douglas Co (specimen HMM 6275, measurements; Swenk, Notes After 1925), and 10 Jun 1990 Scotts Bluff Co. For later dates see Summer (below).

- High counts: 9 between the Rainwater Basin and Sarpy Co 24 Apr 1998, and 5 at Lake McConaughy, Keith Co 13 May 2004. There were totals of 25 statewide in 1999, 22 in 1997, and 21 in 1998.

Summer: Until introduction efforts in Omaha and Lincoln established breeding pairs in 1992 and 2003 respectively, there was only a single report indicative of nesting; Bruner et al (1904) noted that young and old birds were seen 5-19 Aug 1903 around cliffs 8 miles west of Fort Robinson SHP in Sioux Co in and out of a “recess that may have been the nesting site.” However, Mollhoff (2022) did not rule out the possibility these birds may have been migrants based on the date and that young peregrines leave the nest in Jun.

There are several summer reports that are likely wandering immature non-breeders and not attributable to resident birds in Lancaster and Douglas Cos. Summer reports are 2-29 Jun 2025 Hall Co, 11 Jun and 1 Jul-8 Aug 1980 Garden Co, 16 Jun 2022 Crescent Lake NWR, Garden Co, 22 Jun 2013 photographed Buffalo Co, 23 Jun 2011 Frontier Co, 26 Jun 1968 McPherson Co, 30 Jun 2012 Dodge Co, 1 Jul 2016 Lincoln Co, 2 Jul 2021 Banner Co, 5 Jul 2020 Box Butte Reservoir, Dawes Co, 6 Jul 2021 an adult at Niobrara, Knox Co, 7 Jul 2025 Scotts Bluff Co, 10 Jul 2003 Nance Co, 14 Jul 1963 Douglas-Sarpy Cos, 15 Jul 2016 Lincoln Co, 18 Jul 2001 juvenile Harlan Co, and 20 Jul 1988 Lancaster Co.

Panhandle reports may include foraging Rocky Mountains breeders, which are anatum. An adult at Crescent Lake NWR, Garden Co 16 Jun 2022 was at the same general location and using the same perches as a juvenile 10 Aug 2019 and an adult 5 Aug 2021 (Steven Mlodinow, personal communication). These sightings may be of the same individual (that would be three years old in 2022) dispersing from the Rocky Mountains breeding population. Most Peregrine Falcons do not breed until 3-4 years of age.

Fall: Jul 28, 29, 29 <<<>>> Oct 30, Nov 1, 1

Early and late dates above do not include reports from Douglas and Sarpy Cos since 1992 and Lancaster Co since 2003, when breeding birds became established and are resident.

An earlier date is 26 Jul 1970 Custer Co. For earlier dates, see Summer.

Later dates are 14 Nov 2020 Saline Co, 17 Nov 2012 Keith Co, and 17 Nov 2018 Kearney Co.

Peak numbers occur late Sep-early Oct; for Dec and later dates see Winter.

- High counts: 5 at Lake McConaughy 12 Sep 2013, and 4 in Knox Co 8 Oct 2011.

Winter: There are numerous reports Dec through mid-Mar. Most are of presumed resident adults in the vicinity of Omaha and Lincoln. The winter foraging range of the species is unknown, although Palmer (1988) stated that resident birds loosely defend a hunting range that may consist of up to 40 square miles. A circular territory this size implies a foraging radius of 3-4 miles or a maximum distance of 6-8 miles from a nest site.

Documented Dec-Feb records away from the range of Omaha and Lincoln resident breeders are 2 Dec 2016 Lincoln Co, 6 Dec 2005 Lincoln Co, 11 Dec 2021 Crescent Lake NWR, Garden Co, 26-28 Dec 2020 Saunders Co, 7 Jan 2013 Dodge Co, 29 Jan 2012 Franklin Co, 6-9 Feb 2000 Platte Co, 16 Feb 2014 Cass Co, 26 Feb 2016 Saunders Co, and 27 Feb 2016 Sherman Co.

A banding and trapping study by Beingolea and Arcilla (2020) showed that Nearctic Peregrine Falcons, both tundrius and anatum, winter together in Peru; one of the birds recovered in Peru was named Sky King, hatched at the WoodmenLife Tower in Omaha, banded there as a chick 26 Jul 1989, and recovered at Ica, Peru 1 Feb 1995. Sky King nested successfully at the WoodmenLife Tower 1994 and 1995, paired with Kay Cee and fledging one young bird each year.

Comments: This species underwent a severe population decline in North America due to pesticides beginning in the 1940s. By 1964 the population was much reduced, but after restrictions on the pesticide DDT in 1972 the population has recovered (White et al 2020). Reintroduction efforts have also assisted in increasing the population, particularly in mid-latitudes; most Nebraska reports are since 1980.

The low nesting success in 2024 in Omaha and Lincoln is likely partly due to Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI); falcon populations in Iceland and Netherlands have been hard-hit in recent years (Caliendo et al 2025), and single females from Omaha and Lincoln tested positive in 2022 for HPAI (Joel Jorgensen).

Images

Abbreviations

HMM: Hastings Municipal Museum

NGPC: Nebraska Game and Parks Commission

NWR: National Wildlife Refuge

SHP: State Historical Park

UNSM: University of Nebraska State Museum

WPA: Waterfowl Production Area (Federal)

Literature Cited

AviList Core Team, 2025. AviList: The Global Avian Checklist, v2025. https://doi.org/10.2173/avilist.v2025.

Beingolea, O., and N. Arcilla. 2020. Linking Peregrine Falcons’ (Falco peregrinus) wintering areas in Peru with their North American natal and breeding grounds. Journal of Raptor Research 54: 222-232.

Bruner, L., R.H. Wolcott, and M.H. Swenk. 1904. A preliminary review of the birds of Nebraska, with synopses. Klopp and Bartlett, Omaha, Nebraska, USA.

Caliendo, V., B.B. Martin, R.A.M. Fouchier, H. Verdaat, M. Engelsma, N. Beerens, and R. Slaterus. 2025. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Contributes to the Population Decline of the Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus) in The Netherlands. Viruses 17(1), 24; https://doi.org/10.3390/v17010024.

Cortelyou, R.G. 1988. Peregrine Falcon project in Omaha. NBR 56: 81.

Ducey, J.E. 2008. Success Continues for Falcon Project in Omaha. Wild Birds Broadcasting Apr 2008. Wildbirds Broadcasting: Success Continues for Falcon Project in Omaha.

Jorgensen, J.G. 2012. Birds of the Rainwater Basin, Nebraska. Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA.

Mollhoff, W.J. 2022. Nest records of Nebraska birds. Nebraska Ornithologists’ Union Occasional Paper Number 9.

Morris, R. 1992. Peregrine Falcon nesting success in Omaha, Nebraska. NBR 60: 71.

Palmer, R.S., ed. 1988. Handbook of North American birds. Vol. 4. Diurnal Raptors (Part 1). Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

Rapp, W.F. Jr., J.L.C. Rapp, H.E. Baumgarten, and R.A. Moser. 1958. Revised checklist of Nebraska birds. Occasional Papers 5, Nebraska Ornithologists’ Union, Crete, Nebraska, USA.

Robbins, M.B. 2018. The Status and Distribution of Birds in Missouri. University of Kansas Biodiversity Institute, Lawrence, Kansas, USA.

Swenk, M.H. Notes after 1925. Critical notes on specimens in Brooking, Black, and Olson collections made subsequent to January 1, 1925. Handwritten manuscript in the Nebraska Ornithologists’ Union Archives, University of Nebraska State Museum, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA.

Wheeler, B.K. 2003. Raptors of Western North America. Princeton University Press, New Jersey, USA.

White, C.M., N.J. Clum, T.J. Cade, and W.G. Hunt. 2020. Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.perfal.01.

Recommended Citation

Silcock, W.R., and J.G. Jorgensen. 2025. Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus), Version 1.0. In Birds of Nebraska — Online. www.BirdsofNebraska.org

Birds of Nebraska – Online

Updated 25 Aug 2025