Buteo jamaicensis

Thirteen subspecies are recognized by AviList (2025), seven of which occur south of the United States. The others are: alascensis of southeast Alaska and southwest Canada, harlani of central Alaska and northwest Canada, calurus of western North America, borealis of eastern North America, fuertesi of the southwest United States and northern Mexico, and umbrinus of Florida, the Bahamas, and Cuba.

We include the northern subspecies abieticola (Todd 1950, Wheeler 2003, Liguori and Sullivan 2014), although AviList (2025) included it within borealis. See discussion under abieticola below. Wheeler (2003) treats “kriderii” as a pale morph of borealis, which we follow, hereinafter “Krider’s”.

We accept four subspecies as occurring in Nebraska: borealis (including Krider’s), abieticola, calurus, and harlani. Nebraska breeding birds are borealis (Wheeler 2003), although breeding Red-tailed Hawks in the western third of Nebraska are likely to be intergrades with western calurus and a few Krider’s may summer in extreme northwestern Nebraska (see Krider’s, below). Calurus, abieticola, and harlani are regular migrants and winter visitors, calurus statewide, abieticola reported mostly east and central, and harlani mostly in southern and eastern Nebraska. Krider’s is a rare migrant.

Many wintering birds are dark morphs; Rosche (1994) indicated that in some years these outnumber pale morphs in the Keith Co area. A total of 93 birds in Dodge Co 30 Dec 2007 and Sarpy Co 7 Jan 2008 included five harlani, 11 dark morphs, and one rufous morph.

Complicating identification of dark birds in winter is the recently proposed dark morph of abieticola (Iron 2012), which is indistinguishable in the field from calurus. Thus, eBird recommends Nebraska observers reporting dark morph Red-tailed Hawks that are not harlani as “calurus/abieticola“; this designation presumably includes the majority of dark Red-tailed Hawks in winter in Nebraska. On current knowledge (Iron 2012), dark morph abieticola is rare (see also Red-tailed Hawk Project) and the majority of dark morph Red-tailed Hawks in Nebraska are probably calurus. A further complication is eBird’s recommendation to report calurus as calurus/alascensis; alascensis is a northwestern Pacific Coast dark subspecies of Red-tailed Hawk but is unreported in Nebraska.

A hybrid with Rough-legged Hawk has been reported in three recent winters; see https://red-tailed-x-rough-legged-hawk-hybrid/.

Occasionally white (leucistic or possibly albinistic) birds are reported, usually in migration, but one was paired with a normally plumaged bird in central Nebraska 31 Mar 2010. An apparent near-albino (red eye, “touch of red” in tail) in Frontier Co 4 Dec 2016 was likely the same bird that had been wintering there for 6-8 years (T.J. Walker, personal communication).

Red-tailed (Eastern Red-tailed) Hawk

B. j. borealis

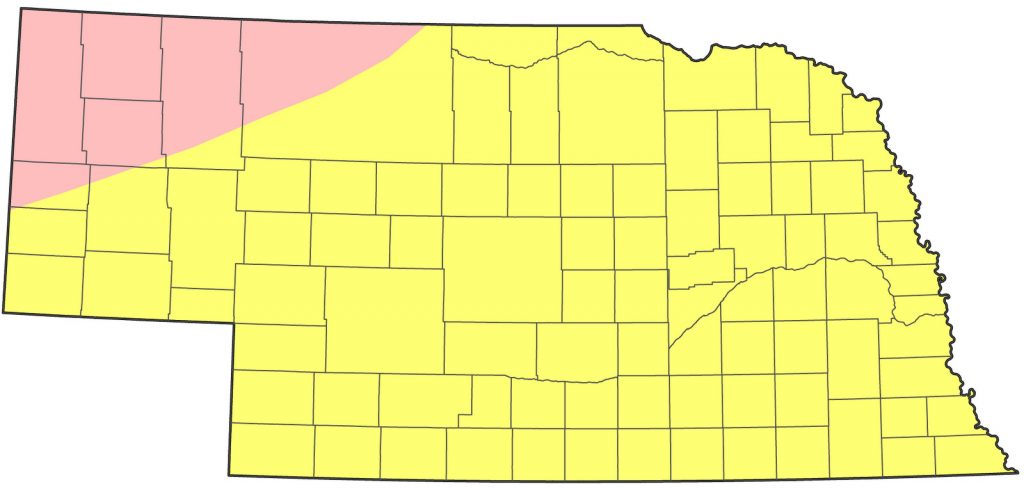

Status: Common regular spring and fall migrant statewide. Fairly common regular resident statewide. Common regular winter visitor south, uncommon north.

Documentation: Specimen: UNSM ZM7666, 9 Sep 1917 Lancaster Co.

Taxonomy: Borealis intergrades with calurus in western Nebraska (see Krider’s below).

Resident: Most Nebraska breeders are resident (Wheeler 2003); apparent pairs of light-colored birds are often seen during winter. BBS data 1966-2019 (Sauer et al 2020) indicate breeding Red-tailed Hawks are evenly distributed across Nebraska and have increased annually at a rate of 2.306% (95% C.I.; 1.133, 3.551) during the period 1966-2019.

-

- Breeding Phenology:

Nest building: 5 Feb-25 May

Copulation: 10 Feb-9 Apr

Eggs/incubation: 1 Mar-28 Jun (Mollhoff 2022)

Nestlings: 20 Mar-21 Jun (later in Panhandle: 21 Jun-1 Jul)

Dependent young: 30 Apr-25 Jul

- Breeding Phenology:

Spring: Migration dates are difficult to discern, although numbers peak in Mar, presumably migrants (borealis) from the northern parts of the species’ breeding range. Wheeler (2003) noted that northward movement of adult borealis and calurus begins at mid-latitudes in late Feb, peaking in numbers mid- to late Mar, with juveniles straggling into Jun.

- High counts 100+ on 2 Mar 2003 in Gage Co, 93 over in 24 minutes, Omaha, Douglas Co 25 Mar 2024, 80 in 300 miles of I-80 9 Apr 2018, 56 on 26 Mar 2000 in Sarpy Co, and 44 between Omaha and Grand Island along I-80 23 Mar 2002.

Fall: As in spring, movements of borealis are difficult to discern, although High Counts suggest peak movement in late Oct. Hitchcock Nature Center Hawk Watch, Pottawattamie Co, Iowa data show migration of Red-tailed Hawks beginning mid-Aug, with highest numbers occurring throughout Oct; average total yearly count through 2022 is 2440 (Hawkcount.org).

- High counts: 208 over Omaha 23 Oct 2009, 63 at Branched Oak Lake, Lancaster Co 31 Oct 2019, and 52 over Bellevue, Sarpy Co 22 Oct 2000.

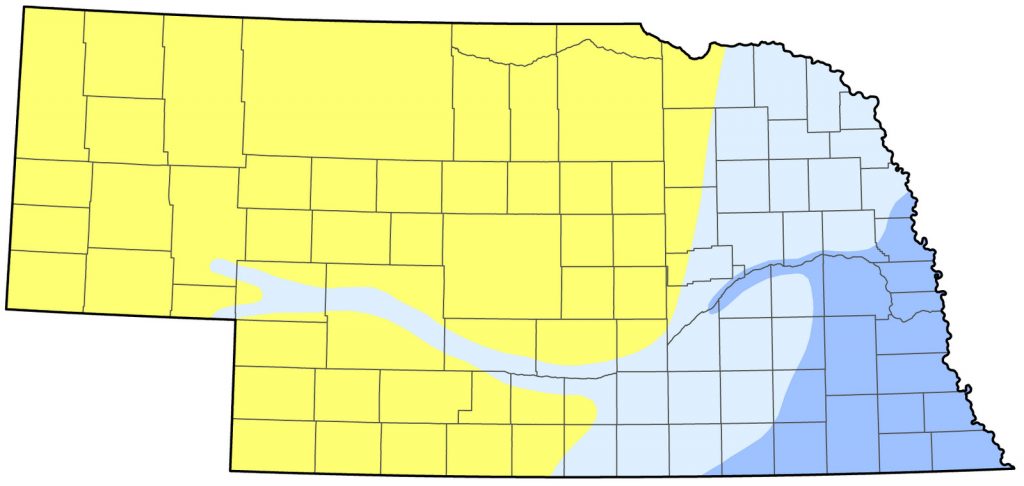

Winter: Red-tailed Hawks winter statewide but are unevenly distributed. CBC data show that they are about five times more numerous per party-hour in the east than in the west. Since 2000, the total number counted on Nebraska CBCs has varied from 262 to 550 and over the 115 years of the CBC, birds per party-hour has increased from virtually zero in the 1940s to around 1.0 in 2014. Distribution maps for Jan-Feb in eBird (eBird.org, accessed Oct 2023) show borealis Red-tailed Hawks concentrated in the east, the Platte and North Platte river valleys southward, and the northwest.

It was considered uncommon to rare in the northwest (Rosche 1982) and uncommon to rare in the western Sandhills during winter (Fred Zeillemaker, personal communication). Lingle (1989) found it to be the most common Buteo along the lower reaches of the North Platte River, counting 10.8 birds per 100 km of highway, although similar counts in the east in 2013 found 48 in 65 miles (46 per 100 km) in Washington and Burt Cos 13 Jan, and 31 in 67 miles (29 per 100 km) in Dodge Co 6 Jan. A roadside survey of wintering hawks in Nemaha Co in 1980-81 and 1981-82 estimated a winter density of 0.28 per square kilometer (Shupe and Collins 1983).

Red-tailed (Krider’s Eastern Red-tailed) Hawk

B. j. borealis (morph Krider’s)

Status: Rare regular spring and fall migrant statewide. Rare casual summer visitor north and northwest. Rare casual winter visitor southeast.

Documentation: Specimen: UNSM ZM11452, 16 Jul 1965 Fort Robinson SP, Dawes Co.

Spring: Mar 6, 6, 6 <<<>>> May 18, 21, 24

Earlier dates are and 23 Feb 2025 Buffalo Co, 24 Feb 2024 Lancaster Co, 27 Feb 2022 Saunders Co, 29 Feb 2020 Otoe Co, 2 Mar 2023 Lincoln Co, and 4 Mar 2023 Pawnee Co.

Later dates are 27 May 2024 Keya Paha Co, and 28 May 2022 Ogallala, Keith Co.

Reports of Krider’s suggest later movement in spring than calurus or borealis; Rosche (1994) stated that in the Keith Co area “most” of the paler breeding birds arrive in Mar and depart in Oct-Nov, possibly a reference to Krider’s.

Summer: The pale morph Krider’s may breed in extreme northwestern Nebraska (Carriker 1902, Bruner et al 1904, AOU 1957, Wheeler 2003, Red-tailed Hawk Project accessed Oct 2024), but there are no confirmed breeding records. The Red-tailed Hawk Project shows the breeding range of Krider’s extending southeastward only as far as northeastern South Dakota.

The only records Jun through mid-Sep are 3 Jun 2011 Holt Co, 3 Jun 2015 Cheyenne Co, 10 Jun 2004 Cherry Co, 13 Jun 2021 Kimball Co, 13 Jun 2023 Agate Fossil Beds, Sioux Co, 1 Jul 2003 Sheridan Co, and 14 Jul 2014 Thomas Co. One photographed west of Kilgore, northern Cherry Co 1 Sep 2024 may have summered there; a recently fledged juvenile was photographed at the same ranch 17 Jun-18 Jul 2025.

Fall: Oct 4, 4, 7 <<<>>> Dec 28, 28, 29

Earlier dates are 19 Sep 2020 Lancaster Co, and 28 Sep 2024 Blaine Co.

Later dates are 1 Jan 2018 Red Willow Co, 2 Jan 2025 Buffalo Co, and 3 Jan 2021 Dodge Co.

Most fall migrants are detected during Oct in the eastern half of the state, with later records concentrated in the Missouri River Valley (see Winter).

Winter: Very few overwinter in Nebraska; larger numbers winter in eastern Kansas and northwestern Missouri. There are only five mid-winter (4 Jan- 22 Feb) records: 7 Jan 2021 Douglas Co, 17 Jan 2022 Washington Co, 27 Jan 2011 Douglas Co, 1 Feb 2025 Cass Co, and 7 Feb 2025 Lincoln Co.

Red-tailed (Northern Red-tailed) Hawk

B. j. abieticola

Status: Uncommon regular winter visitor east, east central, rare casual elsewhere.

Documentation: Photograph: 14 Jan 2018 Otoe Co (Manning 2018).

Taxonomy: This proposed subspecies (Todd 1950) is currently a topic of debate; as noted by Preston and Bean (2020), “More study is needed, but this taxon would appear to meet a similar standard to the others currently considered valid subspecies in North America. In addition to being more heavily marked on average than B. j. borealis, a suite of researchers is currently exploring the strong likelihood that abieticola could be polymorphic, further distinguishing it biologically from borealis.” (see below- Iron 2012). Various recent authors treat this form differently (see Liguori and Sullivan 2014). Some recent authors consider abieticola merely a dark form of borealis rather than a subspecies (Preston and Beane 2020, Liguori and Sullivan 2014). However Red-tailed Hawks with heavy markings occur throughout the breeding range of borealis, not only where abieticola was first described (Liguori and Sullivan 2014). If it is believed that abieticola or birds resembling it, breed across northern Canada and winter on the Great Plains, then it would be expected to occur with some regularity in Nebraska.

Recently, it has been suggested that abieticola has a dark morph that is indistinguishable in the field from calurus (Iron 2012; Red-tailed Hawk Project). Beginning in winter 2020-2021, eBird reporters have used the eBird-suggested category calurus/abieticola, which would include the vast majority of dark Red-tailed Hawks in Nebraska that are not Harlan’s. Because of the little-known status of dark morph abieticola and its apparent rarity, we include reports of calurus/abieticola in the calurus account.

Dickerman (1989) provided the following identification points: “abieticola has broad blackish streaks on the breast, so much so as to make some individuals of the subspecies identifiable in the field. In some specimens, both adults and immatures, the black markings are so broad that they almost-form a solid black band across the breast. Adults from the western portion of the range of abieticola may have ancillary barring in the tail, while those from the eastern part of the range lack such additional barring. The tail of adult abieticola, as in borealis, is darker red than in calurus.”

Winter: Oct 5, 6, 6 <<<>>> Apr 6, 8, 10

Above dates refer to light morph abieticola; dark birds are included in calurus/abieticola (see Western Red-tailed Hawk, below).

Earlier dates all occurred in 2024; there were five reports 5-9 Oct in Hall, Cedar, Knox, and Holt Cos. The previous earliest date was 8 Oct.

Later dates are 16 Apr 2022 Saunders Co, and 17 Apr 2022 Colfax Co.

Although there are records dating back only to 2018, there have been several each year since, suggesting regular occurrence at least in eastern Nebraska. As of Mar 2025, there are about 95 records, only nine in the Central and Panhandle: 8 Oct 2023 Sherman Co, 9 Oct 2023 Phelps Co, 13 Dec 2024 Hall Co, 28 Dec 2021 Harlan Co, 20 Jan 2022 Scotts Bluff Co, 21 Feb 2020 Garden Co, 29 Feb 2025 Keith Co, and 10 Apr 2023 Buffalo Co.

Red-tailed (Western Red-tailed) Hawk

B. j. calurus (Includes dark morph B. J. abieticolA, and Dark morph B. J. alascensis)

Western Red-tailed Hawk at Valentine NWR, Cherry Co 1 Nov 2017. Photo by Joel G. Jorgensen.

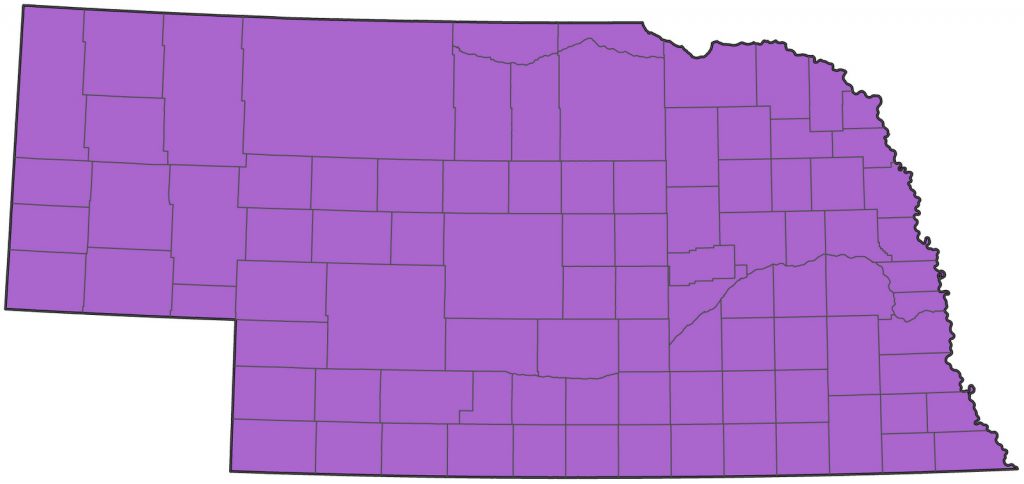

Status: Common spring and fall migrant and winter visitor statewide. Rare casual summer visitor northwest.

Documentation: Specimen: UNSM ZM16366, 26 Sep 1991 Butler Co.

Taxonomy: No pure calurus are known to breed in Nebraska, although intergrades occur in the west (Wheeler 2003).

Reports of dark morph Red-tailed Hawks in Nebraska are reported to eBird as “calurus/abieticola” as the two subspecies are thought to be essentially identical on the winter range. Because proposed dark morph abieticola (Iron 2012) is presumably quite rare, all eBird reports of calurus/abieticola are included in this calurus account. Similarly, the northwestern Pacific Coast subspecies alascensis is not expected to occur in Nebraska and nearby states, and so eBird reports of calurus/alascensis are also included in this calurus account.

Spring: winter <<<>>> Apr 10, 10, 10

“Dark-colored birds” leave late Feb-early Apr although there are later dates 16 Apr 2017 Buffalo Co, 25 Apr 2017 Scotts Bluff Co, 30 Apr 2018 Lake McConaughy, Keith Co, 4 May 2024 (calurus/alascensis) Oliver Reservoir, Kimball Co, 8 May 2010 Clay Co, 9 May 2013, 20 May 2018 Custer Co, and 21 May 2024 (calurus/abieticola) Scotts Bluff Co.

Rosche (1994) cited extreme dates for dark birds in the Keith Co area 23 Sep-18 Apr.

Wheeler (2003) noted that northward movement of adult calurus begins at mid-latitudes in late Feb, peaking in numbers mid- to late Mar, with juveniles straggling into Jun.

Summer: In northwestern Nebraska there is the possibility of intergrades or even adults occurring in summer, as well as the late-migrating immatures into Jun mentioned above (Wheeler 2003). The few reports are 9 Jun 2017 Cheyenne Co; 9 Jun 2022 two adults Scotts Bluff Co; 13 Jun 2021 Kimball Co; two, reported as “calurus” by an experienced observer, along Hawthorne Road, Dawes Co 1 Jul 2003; one in Smiley Canyon, Sioux Co 25 Jun 2018; one “moderately” marked in Scotts Bluff Co 28 Jun 2024, one in Scotts Bluff Co 9 Jul 2015; and an adult 10 Jul 2022 Scotts Bluff Co.

Fall: Sep 29, Oct 1, 2 <<<>>> winter

Earlier dates are 15 Aug 2020 Scotts Bluff Co, 15 Aug 2020 Kimball Co, 25 Aug 2024 Dawes Co, 11 Sep 2016 Dundy Co, 11 Sep 2023 Lake Alice, Scotts Bluff Co, 18 Sep 2017 Dundy Co, and 26 Sep 2017 Phelps Co.

Rosche (1994) cited extreme dates for dark birds in the Keith Co area 23 Sep-18 Apr. Wheeler (2003) noted that juveniles of calurus begin moving south in mid-Aug, and the northern Great Plains are “filled with incredible numbers of juveniles” in late Sep and early Oct. Taylor and Van Vleet (1888) cited two specimens collected by Baird in Aug 1857 near North Platte, Lincoln Co.

Winter: This form winters across Nebraska, with fewer northwestward.

Red-tailed (Harlan’s) Hawk

B. j. harlani

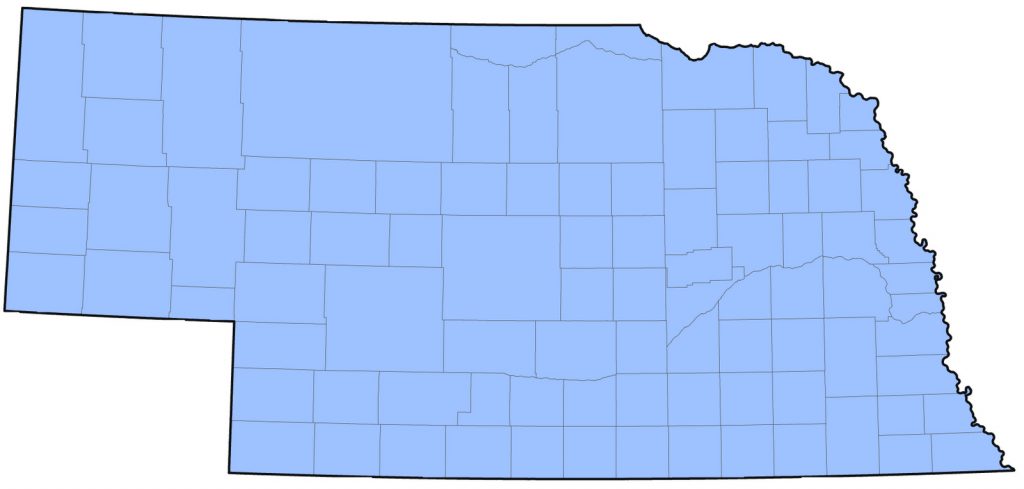

Status: Uncommon regular spring and fall migrant statewide. Uncommon regular winter visitor east and Platte River Valley, rare North Platte River Valley, rare casual elsewhere.

Documentation: Specimen: UNSM ZM12515 28 Mar 1911 Crete, Saline Co

Taxonomy: Preston and Beane (2020) suggest harlani may “prove to be [a full species] given limited interbreeding with neighboring populations where ranges meet” but the case against species status was presented in detail by Sullivan et al (2018) and is followed here. It is treated as a subspecies by AviList (2025) and the Red-tailed Hawk Project; see also Clark (2018).

Spring: winter <<<>>> Apr 17, 18, 18

Later dates are an adult near Verdigre, Knox Co 22 Apr 2021, a juvenile near Creighton, Knox Co 22 Apr 2021, 25 Apr 2022 Scotts Bluff Co, an adult near Niobrara, Knox Co 30 Apr 2021, 30 Apr 2022 Douglas Co, and 1 May 2022 Thomas Co. Very late dates, likely non-breeding immatures, are of a dark morph juvenile in Butler Co 17 May 2020, one at Lake Minatare, Scotts Bluff Co 21 May 2024, a light morph juvenile/immature near Harrison, Sioux Co 13 Jun 2021, and a first summer immature at Kiowa WMA, Scotts Bluff Co 13 Jun 2022.

Rosche (1994) cited extreme dates for harlani in the Keith Co 26 Oct-24 Mar. There are specimens of harlani at UNSM covering the period 13 Nov-28 Mar.

Fall: Sep 26, 27, 27 <<<>>> winter

Earlier dates are 12 Sep 2021 Johnson Co, and 23 Sep 2018 Buffalo Co.

Dark-colored birds are noted as early as late Sep; there is a specimen of harlani, HMM 2806, collected at Tilden, Antelope/Madison Cos 30 Sep 1918.

Winter: This form winters (Dec-Feb) in highest numbers in the east and in the Platte and North Platte River valleys (Wheeler 2003, eBird.org, accessed Oct 2023). Away from these areas, there are only about 34 records Dec-Feb (eBird.org, accessed Mar 2025).

The North Platte CBC 28 Dec 2013 found a count high there of six harlani among the 33 Red-tailed Hawks reported.

Images

Abbreviations

AOU: American Ornithologists’ Union

BBS: Breeding Bird Survey

CBC: Christmas Bird Count

HMM: Hastings Municipal Museum

NWR: National Wildlife Refuge

SP: State Park

UNSM: University of Nebraska State Museum

WMA: Wildlife Management Area (State)

Literature Cited

American Ornithologists’ Union [AOU]. 1957. The AOU Check-list of North American birds, 5th ed. Port City Press, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

AviList Core Team, 2025. AviList: The Global Avian Checklist, v2025. https://doi.org/10.2173/avilist.v2025.

Bruner, L., R.H. Wolcott, and M.H. Swenk. 1904. A preliminary review of the birds of Nebraska, with synopses. Klopp and Bartlett, Omaha, Nebraska, USA.

Carriker, M.A., Jr. 1902. Notes on the nesting of some Sioux County birds. Proc. Nebraska Ornithologists’ Union 3: 75-89.

Clark, W.S. 2018. Taxonomic status of Harlan’s Hawk Buteo jamaicensis harlani (Aves: Accipitriformes). Zootaxa 4425: 223-343.

Dickerman, R.W. 1989. Identification of Red-tailed Hawks wintering in Kansas. Kansas Ornithological Society Bulletin 40: 33-34.

Iron, J. 2012. Toronto Ornithological Club Newsletter, Feb, pp 1-6.

Liguori, J., and B.L. Sullivan. 2014. Northern Red-tailed Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis abieticola) revisited. North American Birds 67: 374-383.

Lingle, G.R. 1989. Winter raptor use of the Platte and North Platte River valleys in south central Nebraska. Prairie Naturalist 21: 1-16.

Manning, S. 2018. Checklist S41919712: Highway 75, Otoe County. eBird.org, accessed 16 Jun 2018.

Mollhoff, W.J. 2022. Nest records of Nebraska birds. Nebraska Ornithologists’ Union Occasional Paper Number 9.

Preston, C.R. and R.D. Beane. 2020. Red-tailed Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.rethaw.01.

Rosche, R.C. 1982. Birds of northwestern Nebraska and southwestern South Dakota, an annotated checklist. Cottonwood Press, Crawford, Nebraska, USA.

Rosche, R.C. 1994. Birds of the Lake McConaughy area and the North Platte River valley, Nebraska. Published by the author, Chadron, Nebraska, USA.

Sauer, J.R., W.A. Link, and J.E. Hines. 2020. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Analysis Results 1966 – 2019: U.S. Geological Survey data release, https://doi.org/10.5066/P96A7675.

Shupe, S., and R. Collins. 1983. A winter roadside survey of hawks in eastern Nemaha County, Nebraska. NBR 51: 19-22.

Sullivan, B.L. J. Liguori, M. Borlé, F. Nicoletti, K. Bardon, J. Lish, N. Paprocki, B. Robinson, and S. Bourdages. 2018. AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America, Proposal Set 2019-A. http://checklist.aou.org/assets/proposals/PDF/2019-A.pdf.

Taylor, W.E., and A.H. Van Vleet. 1888. Notes on Nebraska birds. Ornithologist and Oologist. 13: 49-51.

Todd, W. E. C. 1950. A Northern Race of Red-tailed Hawk. Annals of the Carnegie Museum 31: 289-296.

Wheeler, B.K. 2003. Raptors of Western North America. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, USA.

Recommended Citation

Silcock, W.R., and J.G. Jorgensen. 2025. Red-tailed Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis). In Birds of Nebraska — Online. www.BirdsofNebraska.org

Birds of Nebraska – Online

Updated 3 Sep 2025