Antigone canadensis canadensis, A. c. tabida

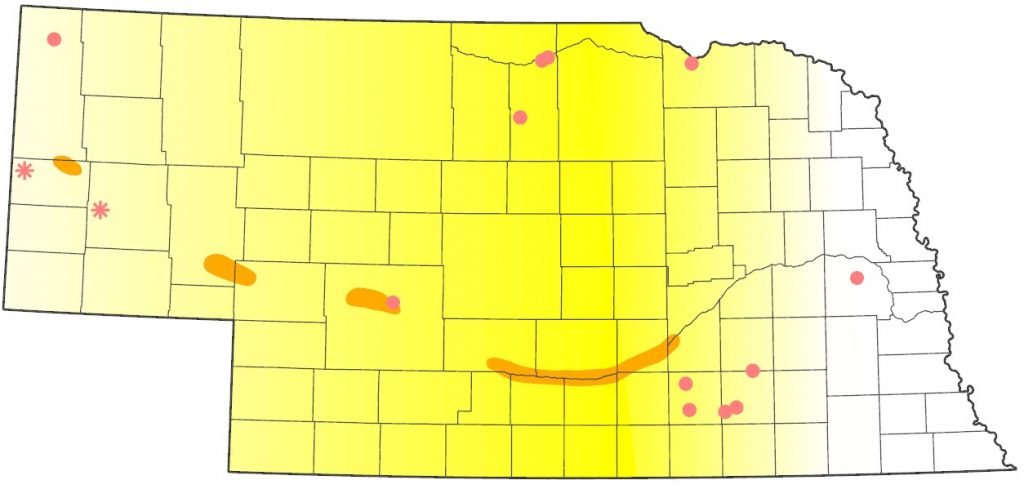

Status: Increasing. Abundant regular spring and fall migrant central, common west, uncommon east. Rare regular breeder locally statewide. Rare casual summer visitor statewide. Rare casual winter visitor central Platte River Valley, accidental east.

Documentation: Specimen: UNSM ZM7836, 19 Mar 1959 Overton, Dawson Co.

Taxonomy: This species was moved recently from genus Grus to genus Antigone (Krajewski et al 2010).

Recent authors (AviList 2025) recognize five subspecies, following Rhymer et al (2001), who discerned two clades, one consisting of long-distance migrant subspecies canadensis and the other migrant North American breeder tabida and sedentary subspecies pulla of Mississippi and pratensis of Georgia. The fifth taxon, Cuban nesiotes was not included in the Rhymer et al (2001) study.

Rhymer et al (2001) merged former subspecies rowani into tabida as genetically indistinguishable; tabida has precedence. Pyle (2025) synonymized all five subspecies (per AviList 2025) as canadensis based on their not meeting the generally accepted 75% rule for subspecies diagnosability.

Nebraska birds are canadensis and tabida.

In a recent publication (Central Flyway Webless Migratory Game Bird Technical Committee 2018, “CFMC”) regarding the Mid-Continent Population (MCP) of Sandhill Cranes, satellite telemetry studies are cited that suggest four MCP “breeding affiliations” i.e. non-contiguous breeding sub-populations: Western Alaska-Siberia, northern Canada-Nunavut, West-central Canada-Alaska, and East-central Canada/Minnesota (Krapu et al 2011, 2014). Based on mitochondrial DNA studies (Krapu 2011, 2014), the first two affiliations are >92% subspecies canadensis, and the last two >85% tabida (CFMC Table A1). The ranges of these breeding affiliations are shown in MCP Figure 2 (page 8); all four affiliations stage on the Platte River in spring.

Lingle (1994) considered about 80% of the Sandhill Cranes which migrate through Nebraska to be canadensis (Lesser Sandhill Crane), and 20% rowani plus tabida (Greater Sandhill Crane). Recent genetic sampling of the population in the central Platte River Valley suggests, however, that Greater Sandhill Cranes (tabida plus rowani) comprise about 42% of the total (Krapu et al 2014).

A large number of Sandhill Cranes killed in a severe hailstorm in Hall Co 24 Mar 1996 were expertly prepared by Thomas Labedz at UNSM; exposed culmen measurements of single females at the large and small extremes clearly assigned them to tabida (culmen 127, tarsus 220, ZM17404) and canadensis (culmen 89, tarsus 162, ZM17423) respectively, based on measurements in Pyle (2008). There were numerous intermediate birds; presumably these comprised the lower end of the mensural range of tabida (sensu Rhymer et al 2001, Pyle 2008).

Spring: Jan 8, 8, 9 <<<>>> Jun 6, 7, 9

Early dates above are of groups larger than 30 birds that were not present earlier. Arrival dates have steadily become earlier in recent years, averaging about 1 May in 1920, 10 Feb in 1965, and 1 Feb in 2010 (Harner et al 2015). Sharpe et al (2001) cited early spring arrival dates 24, 24, 25 Jan.

Later reports of probable migrants are of 1-2 in Buffalo Co 6-12 Jun 2024, one with an injured wing, a group of up to 11 adults at Kiowa WMA, Sioux Co 3-27 Jun 2025, and a group of five at Ayr Lake, Adams Co 12 Jun 2021. “Spring stragglers have been seen as late as “early June” in the Keith Co area (Brown and Brown 2001). Most depart by the end of Apr.

The first arrivals often appear in late Jan, although these birds may retreat southward during periods of inclement winter weather. Early migrants in numbers were at least 3000 in Hall Co 1-9 Jan 2025, and 600 in Adams Co 3 Jan 2021. In 2020, Crane Trust aerial surveys tallied 6150 cranes on 11 Feb, 13,120 on 18 Feb, and 34,500 on 24 Feb.

Breeders returning to territory may arrive quite early; 2-4 were at the Lake Wanahoo, Saunders Co breeding site 4-6 Jan 2019.

There appear to be two discrete groups apart from those in the central Platte River Valley: about 25,000 occupy an area east of Hershey in Lincoln Co where counts have been in the 10,000-25,000 range since at least 2005 (Silcock 2005, 2013) until 2025, when 80,000 were reported 22 Mar north of North Platte; 40,000-50,000 used meadows in the Clear Creek Marshes, Garden Co in 2005 (Silcock 2005), perhaps fewer in 2025, when peak report was 10,000 near Lewellen on 15 Mar. Numbers are increasing in Scotts Bluff Co, where up to 7500 were present 7 Apr 2018 and 9750 near Lake Minatare 28 Mar 2021.

Since the 1990s, when modern breeding began, most sightings into May and Jun in suitable habitat and/or long the central and western Platte River Valleys are likely non-breeding sub-adults, although there are some known breeding locations (see Summer).

In spring, this species has become regular in the east; flocks generally consist of fewer than 100 birds, although an unprecedented report of 47,000 at Bohemia Prairie WMA, Knox Co 26 Mar 2025 must have been of birds migrating north from the Central Platte Valley. More usual are reports of “hundreds” over Creighton, Knox Co 23 Mar 2015 and 1500 at Deep Well WMA, Hamilton Co 14 Mar 2018. An early single was in a cornfield in Holt Co 15 Jan 2025; it may have been one of a pair sighted there Dec 2024.

Birds trapped and outfitted with satellite transmitters (n=153) along the Platte River 1998-2003 during spring subsequently migrated to points that collectively covered a large geographic area encompassing eastern Hudson Bay west across Canada extending to portions of eastern Siberia (Krapu et al 2011).

Estimates of the number of Sandhill Cranes stopping over in the central Platte River Valley are variable from year to year, but estimates have generally been around 500,000 to 660,000 birds (Dubovsky 2018, Caven et al 2019a). Numbers have increased since about 2007 with a notable spike of 1,005,612 birds estimated to be present in the central Platte River Valley during spring 2018 (Dubovsky 2018), followed by a similar total of 946,000 in spring 2019 (Liddick 2019). More recently, however, Caven et al (2019b) in a modeling analysis of several data sources, concluded that the most likely peak estimate for 2018 and 2019 was 1.27 million overall, including 220,000 in the North Platte River Valley. The peak Crane Trust aerial count in 2025 reported by Bethany Ostrom of the Trust was 736,000 +/- 55,000 between Chapman and Overton on 17 Mar, a record for this census, which tends to undercount the cranes. See Comments (below).

Sandhill Crane migration is apparently also shifting temporally based on weekly aerial surveys conducted by the Crane Trust (cranetrust.org), as birds are arriving and numbers are peaking earlier in spring than has been traditionally observed. Peak numbers traditionally occurred 20 Mar-5 Apr, when large numbers were noted between Grand Island and Kearney (Lingle 1994). Surveys conducted during the last week in February by the Crane Trust (cranetrust.org) during the early part of migration show large increase in numbers in the area between Chapman, Merrick Co and Overton, Dawson Co; for 2017 and 2016, 194,825 (+/- 7.3%) and 213,650 (+/-5.1%) were counted respectively, whereas the highest previous tally reported for these surveys was in 2009, when 62,900 were present. Caven et al (2019a) found that Sandhill Crane migration dates advanced by about one day per year from 2002 to 2017; the peak has occurred between 8 Mar and 8 Apr in 2002-2017 (Caven et al 2019b). Climate change, land use change, and habitat loss were implicated (see Comments).

Sandhill Crane staging patterns in the central and upper Platte River regions have changed in response to changes in riverine roosting habitat and also changes in land use (Krapu et al 2014, see Comments). In addition, increasing numbers have been observed in Lincoln, Keith and Garden Counties in recent years and others have noted concentrations pushing east of the traditional staging areas in the Big Bend reach of the Platte River (Caven et al 2019a).

Summer: Sandhill Cranes nested in most of Nebraska until about the beginning of the 20th century (Bruner et al 1904). Unregulated hunting, coupled with habitat loss, contributed to the species’ extirpation as a breeder.

Iowa’s first breeding record in about 100 years was in 1992 (Kent and Dinsmore 1996), and, beginning in the mid-1990s, sightings of juveniles with adults in Nebraska began to accumulate in the Rainwater Basin (Jorgensen 2002, 2012). Breeding was first confirmed when a pair with two downy colts was found at Harvard WPA, Clay Co 29 May 1999, and a pair with a single juvenile was found in early Jun the same year at Kissinger Basin WMA, Clay Co (Hoffman 1999). Evidence suggests breeding had probably occurred previously; in 1994, two adults and two juveniles were seen in Clay Co (Jorgensen 2002), in 1995, a family group was in Fillmore Co 3 Sep, and in 1998, two adults with two juveniles were seen 16-22 Aug 1998 at a small private basin in eastern Clay Co where an adult had been observed Aug 1994 (Jorgensen 2002). During the same period, 1992-1999, there were seven summer reports of adults, including pairs, in the Rainwater Basin (Jorgensen 2002) and one report in Platte Co in 1995.

Jorgensen (2002, 2003, 2012) summarized the breeding season observations in the eastern Rainwater Basin; there were six breeding records at three locations. Since then, there was no confirmed breeding 2011-2015 in the Rainwater Basin even though adults and pairs were observed somewhat regularly during summer. In 2019, family groups consisting of two adults and two juveniles were observed at County Line WPA, York and Fillmore Cos on 12 July and Harvard WPA, Clay Co on 17 August indicating local breeding (Jorgensen and Brenner 2019). Although these are the eighth and ninth breeding records for the Rainwater Basin (Jorgensen and Brenner 2019), variable water levels at Rainwater Basin wetlands may preclude regular nesting by this species in this region. A potential breeding pair, accompanied by subadults, was courting at Straightwater WMA, Seward Co 13-20 May 2022, and likely the same pair was at nearby North Lake Basin WMA 12-15 May 2022. One was at County Line Marsh WPA, Fillmore Co 5 Jul 2021, another at Kirkpatrick North WMA, York Co 31 Jul 2022, and two were at Marsh Duck WMA, York Co 3 Jul 2022.

Since 2000, breeding has occurred at widespread additional locations. Potential breeding pairs occupy known territories by mid-Apr; examples are 14 Apr 2022 near North Platte, Lincoln Co and 16 Apr 2022 near Colon, Saunders Co.

A pair summered in 2002 in the vicinity of Hat Creek Basin Ranch, Sioux Co, but no young were seen. The adults returned in 2003 and raised two young, the family group foraging in meadow and hayed meadow stubble. The adults returned in 2004 but remained only until Jun because of the very dry conditions and lack of water (Larry Wickersham, personal communication). In the same area, along Bodarc Road, a pair with a colt was seen 14 Jun 2013, and in 2024 a pair with a colt were northeast of Harrison, Sioux Co 8 Aug (Shelly Steffl, personal communication), presumably also in the Bodarc Road area. Two were at Toadstool Road Swamp, Sioux Co 24 Aug 2019.

A pair at Chet and Jane Fleisbach WMA at Facus Springs, Morrill Co, began breeding in 2005, raising a colt that year, then 1-2 each year through 2011, but no colt was seen in 2012 and there were no reports 2013-2015, until a pair with a colt was seen 2 Jun 2016. A pair was present in 2020, but as of 1 Jul no young had been seen, and again 20 May and 16 Jun 2022.

A pair with two juveniles in Rock Co 15 Aug 2006 suggested breeding there; adults with two colts were present 18 Jun 2008. Breeding occurred at Hutton Ranch Sanctuary, Rock Co (owned and managed by Audubon of Kansas) in 2013, where two colts were fledged but one was found dead and the fate of the other was unknown. Breeding again occurred there in 2017 (Gordon Warrick, personal communication) and also just west of there on private property and has occurred each year since then. An adult in brown plumage was in the area 31 May 2018 and a pair of adults was there 25 Jul, but no young were seen. One adult was reported at Hutton Ranch Sanctuary 13-14 Jun 2019, a pair with a colt 19 Jul 2020, a pair with two colts in 2021, a pair with one colt 8 Jun 2022, and a pair and a colt 1 Jun-25 Aug 2023. Two along the Niobrara River northeast of Bassett in Rock Co in late Jul 2020 may have been the Hutton Sanctuary birds, as may have been one along Highway 137 in Keya Paha Co 3 Jun 2020.

Two near Twin Lakes WMA in southwest Rock Co 2 Sep 2018 may have been breeding; two were there 13 Jun 2019, one on 8 Jul 2021, and in 2022 two adults with two colts were there 25 Jul (Matt Rahko, eBird.org) and 22 Aug (eBird.org). In 2023 one was there 3 Jun.

A pair was seen at Kiowa WMA, Scotts Bluff Co in 2009-2010, but no colts were seen until there were brief glimpses of probably two colts 21 Jun 2011; a colt was present 26 May 2012, but none were seen 2013-2014. In 2015 the pair had a half-grown young bird 16 Jul and two young were with the adults 10 Oct. Only one adult was seen there 11 Jun 2017, but an adult and colt were photographed there 25 May 2018 and adults were there 31 Jul and 1 Aug 2018. An adult was seen there 22 May 2021, and two were west of the WMA 19 Jun 2022. In 2023, two were at the WMA 23 Jun 2023, and a family group of four which may have been the Kiowa WMA breeders were 7-8 miles to the northeast 27 Jul.

A pair with two young was seen 10 Jun 2017 at Agate Fossil Beds NM, Sioux Co; cranes were heard but not seen in mid-Jun 2018 in the same location. An adult with a chick was seen 7-8 miles further west at Agate 2 Jul 2018, possibly a different breeding pair based on the relatively young chicks seen. One was in the area 14 Jun 2021; it was thought breeding had occurred there for about five years (fide Steven Mlodinow). In 2022 there were reports 2 Jun-1 Aug of mostly heard birds.

An apparent first record for Grant Co was of one 24 Jul 2024.

Paired birds have been in Knox Co around the confluence of the Verdigre and Niobrara Rivers for several years and have bred there; a pair was seen there 29 Jul 2017, and a pair seen earlier on 20 Jun at Bazile Creek WMA, about 3-4 miles east, were likely the same birds. There were several sightings south of Niobrara, including a young bird, in 2020, and one was seen 20 Jul 2021.

In Saunders Co, reports of adults from a wetland one mile north of Lake Wanahoo in 2017 were suggestive of breeding there; one was there 1 Jul and three on 25 Jul, followed by several reports of three through 12 Nov. Two brown adults were in the same area 21 Jun 2018, two were there 6 Aug 2019, and two were seen sporadically 31 Jul-1 Oct 2020. Two were seen in the wetlands to the north 25-28 Mar 2021 (Paula Hoppe, pers. comm.), but only one was seen through 8 May, suggesting a nesting attempt; breeding was finally confirmed with sighting of adults with a colt 13 Jun-19 Jul (Weldon and Paula Hoppe, eBird.org). Two were in the area 5 Jul-1 Aug 2022, three 18 Aug-24 Sep 2023, and two 2-10 Aug 2024.

A pair with a colt was photographed in the North Platte, Lincoln Co area 23 May 2021 (LaVerne James fide T.J. Walker); breeding had been suspected and was finally proven there with the sightings at different locations of adults with one colt 9-10 Jun and adults with two colts 18 Jul (Boni Edwards, eBird.org); the two locations are about three miles apart, indicating two breeding pairs. A pair was seen there with a colt 3 Jun 2022, three 15 Aug-4 Oct 2023, and two on 13 Aug 2024.

A possible new breeding location is Wellfleet WMA, Lincoln Co, where breeding may have occurred in 2019 and 2020; in 2020 two adults were acting territorially through 27 Jul although no nests or young have been found. Somewhat oddly, two birds were calling continuously on a hilltop at Hayes Center WMA, Hayes Co 4 Apr 2021, some 15 miles from Wellfleet.

There are numerous reports statewide 8 Jun-23 Aug of adults, often in suitable breeding habitat, but without evidence of breeding. Most of these reports may be of summering sub-adults, but some may be local breeders or breeders on the move or even failed breeders. A photo of eight birds in Lincoln Co 8-9 May 2015 showed four birds resembling adults and four young birds; yearlings of tabida may remain in pre-breeding flocks during their second summer (Gerber et al 2020), thus the older birds in the flock were likely non-breeding sub-adults. Similar reports are of two brown birds foraging in a flooded soybean field 24 Jul-18 Aug 2018 in Dakota Co, a family group in Wayne Co 28 Jul-5 Aug 2020, and one at Eppley Airfield, Douglas Co, hardly suitable breeding habitat, 28 Jul 2015, probably a wandering non-breeder.

An interesting sighting was the copulation of a pair of Greater Sandhill Cranes (A. c. tabida) along the Platte River in Hall Co 9 Mar 2017 (Caven and Buckley 2017). This date is about a month earlier and further south than previous egg dates and known breeding locations (see above) in Nebraska; however, as discussed below (see Comments), the use of wet meadows in the Central Platte River Valley is important in stimulation of pair bonding (Tacha 1988). In 2018, Malzahn et al (2018) documented the presence in the Central Platte River Valley of 7-8 cranes in nine locations 15 May-7 Jun, including two pairs at different locations 15 May. However, Malzahn et al (2018) noted that all birds had departed by 7 Jun, suggesting that the delay was needed for the birds to improve their physical condition before resuming migration.

Fall: Aug 16, 18, 18<<<>>> Dec 15, 17, 18

Late dates above are away from Hall Co, where wintering occurs most years; see Winter.

Later dates away from Hall Co are 15 Dec 1990 Buffalo Co, 15 Dec 2023 (2) Buffalo Co, 25 Dec 2024 (13) Lincoln Co, 26 Dec 1994 Buffalo Co,

Fall migration is markedly different from spring migration. Sandhill Cranes migrate quickly through the state, stop over for relatively brief periods and do not concentrate along the Platte River in central Nebraska. Lingle (1994) noted peak numbers are lower than 10,000, usually occur in the second half of Oct, and usually in the western half of the state. Rosche (1992) considered it “abundant to very abundant” in fall in the northwest. High Counts (below) are in the first half of Oct and indeed reflect a westerly distribution. Some 90% of fall reports are in Oct, 60% of these in the period 5-20 Oct (Lingle 1994).

Arrival of migrants is in late Aug.

Of interest is the observation that highest numbers in the east occur somewhat later, in Nov (see High Counts). It has been suggested that most Canadian and United States breeders migrate to the east of westerly-migrating canadensis, albeit with some overlap (Tremaine 1970, Krapu et al 2014). Sandhill Cranes are, however, uncommon in the east, generally occurring in small flocks of fewer than 100 birds, although following very strong northwesterly winds, an amazing 1200 were in eastern Lancaster Co 11 Nov 1998 and 336 over Blair, Washington Co the same day.

Most depart by early Dec; see Winter (below).

- High counts: 50,000 near Doniphan, Hall Co 30 Nov 2024, 30,000 in Morrill Co 7 Oct 1994, 25,000 at Alda Bridge, Hall Co 15 Nov 2023, and 5416 in Scotts Bluff Co 16 Oct 1999. In the east, 1200 in Lancaster Co 11 Nov 1998, 500 over Dodge Co 19 Nov 2015, and 314 in Madison Co 6 Nov 2022.

Winter: Wintering has occurred on occasion in the Central Platte Valley prior to 2011-2012 (Lingle 1994), although 5000 near Grand Island, Hall Co 15 Dec 1990 departed during “arctic weather 2-3 days later” (Harner et al 2015) and so did not overwinter. However, winter of 2011-2012 saw an unprecedented influx, followed in winter 2012-2013 by a similar though less impressive wintering event. Harner et al (2015) suggested that severe drought on wintering grounds in Texas along with record warm temperatures and lack of snow cover in Nebraska may have contributed to the influx of cranes. At least 4000-5000 were in the central Platte River Valley late Dec 2011-early Jan 2012, 1300 on 23 Jan 2012, and 4590 on 1 Jan 2012 (Harner et al 2015). Around the same time, another estimate was 7000 in Buffalo Co 29 Dec, and there were 30 in each of Dawson and Hamilton Cos and 75 in York Co as well as 800 in Buffalo Co 1 Jan 2012, but, oddly, only 45 in Hall Co. Again, in 2012-2013, between 200 and 1000 wintered in the Grand Island-Doniphan area; arrival of spring migrants was noted in the area 10 Feb, when numbers around Doniphan “increased dramatically” (Silcock 2013). In 2013-2014, no cranes were noted in midwinter (Harner et al 2015).

It seems there is notable winter (mid-Dec through mid-Jan) movement in recent years, likely indicative of increasing propensity for Sandhill Cranes to move in response to variable and apparently increasingly warm winters. Examples of large numbers arriving in late Dec only to diminish into Jan have occurred in three recent winters (following numbers are years of winter, peak tally, best earlier tally, best later tally): 2020-2021, 300 on 8 Dec, 1000 on 29 Dec, 850 on 3 Jan; 2021-2022, 500 on 3 Dec, 5000 on 28 Dec, 200 on 8 Jan; 2023-2024, 200 on 3 Dec, 9700 on 16 Dec, 2500 on 7 Jan.

Elsewhere, the only records for midwinter (Jan), and the only such records for the east, are of two in Sarpy Co 4 Jan-8 Feb 2023, and one in the area of the UNL East Camus, Lancaster Co 22 Jan-2 Feb 2025.

Comments: Sandhill Crane migration and stopover in Nebraska, and specifically along the Platte River, has changed over time in response to human activities. Prior to settlement by European Americans, Sandhill Cranes occurred in lower densities and were more widely distributed along the Platte River during spring and likely primarily foraged in wet meadows (Krapu et al. 2014). Unregulated and illegal hunting in the late 1800s and early 20th Century may have affected crane use on the river (Krapu et al. 2014). However, water development in the 20th Century was more impactful, reducing suitable roosting habitat (open wetted channel widths > 50 m) as woody vegetation rapidly colonized former river channels (Krapu et al. 2014, Williams 1978). By the 1950s, spring staging was apparently no longer occurring between Cozad and the confluence of the North and South Platte rivers due to lack of suitable roosting habitat (Krapu et al. 2014). Water development and land conversion also reduced wet meadow habitats, but waste corn from farming became a dominant component of cranes’ diet. Presently, favorable roosting habitat is mostly maintained by mechanical clearing and consequently Sandhill Cranes have reliably concentrated in the same areas primarily between Grand Island and Lexington for many years.

Sandhill Crane use of the Platte River valley continues to change in response to changing land use and resource availability (Krapu et al. 2014, Buckley 2011, Caven et al 2019a, Fowler 2019). Waste corn availability has been reduced due to more efficient harvesting equipment, as well as competition from Snow and Ross’s geese (Pearse et al. 2010, Krapu et al 2004, Sherfy et al 2011). In response, Sandhill Cranes are, in some instances, traveling farther from river roosting sites or to areas not frequently used in the past (e.g., north of Interstate 80) to forage (Krapu et al. 2014). Future shifts in agricultural practices that influence availability of waste corn and changes in open river channel roosting habitat will likely continue to affect Sandhill Crane use in the Platte River valley.

Stopover duration in the Central Platte River Valley varies by “affiliation” (see Taxonomy) from 18-28 days, with longer distance migrants (mostly Lesser Sandhill Cranes) staying longer (Krapu et al 2014). Greater Sandhill Cranes arrive earlier, stay a shorter period, and leave earlier than Lesser Sandhill Cranes (Krapu et al 2014). During the stopover, the average crane gains about 0.5 pounds of fat (Lingle 1994).

Reddish or brown Sandhill Cranes are reported fairly often, often in winter and spring; at these times of the year, these birds may have skipped their pre-basic molt the previous fall, possibly due to some type of pathology, and are “stuck” in last summer’s rusty and now heavily worn plumage (Rick Wright, pers. comm.). A possible pathology is infestation with feather mites, causing a situation analogous to mange in coyotes (Gary Lingle, pers. comm.). Birds with serious mite infestations are weak and can be run down and captured on the run; the infestation is simply and usually successfully treated in bird rehabilitation (Dave Brandt, pers. comm.). Reddish birds seen in summer, such as pairs breeding in Nebraska, may have stained feathers resulting from rubbing their feathers with soil; the soil oxidizes and produces the red color (Joel Jorgensen, pers. observation).

Images

Abbreviations

CBC: Christmas Bird Count

NM: National Monument

NPS: National Park Service

UNSM: University of Nebraska State Museum

WMA: Wildlife Management Area (State)

WPA: Waterfowl Production Area (Federal)

Acknowledgement

Andrew Caven provided numerous helpful comments that improved this species account.

Literature Cited

AviList Core Team, 2025. AviList: The Global Avian Checklist, v2025. https://doi.org/10.2173/avilist.v2025.

Brown, C.R., and M.B. Brown. 2001. Birds of the Cedar Point Biological Station. Occasional Papers of the Cedar Point Biological Station, No. 1.

Bruner, L., R.H. Wolcott, and M.H. Swenk. 1904. A preliminary review of the birds of Nebraska, with synopses. Klopp and Bartlett, Omaha, Nebraska, USA.

Buckley, T.J. 2011. Habitat use and abundance patterns of Sandhill Cranes in the Central Platte River Valley, Nebraska, 2003-2010. Master’s Thesis. Lincoln: University of Nebraska.

Caven, A. 2018. Sandhill Crane counts – week 6. Crane Trust blog post, accessed 2 April 2018.

Caven, A.J., and E.M.B. Buckley. 2017. Greater Sandhill Crane (Antigone canadensis tabida) copulation detected along the Big Bend of the Platte River, south-central Nebraska. NBR 85: 83-84.

Caven, A.J.; E.M.B. Buckley, K.C. King, J.D. Wiese, D.M. Baasch, G.D. Wright, M.J. Harner, A.T. Pearse, M. Rabbe, D.M. Varner, B. Krohn, N. Arcilla, K.D. Schroeder, and K.F. Dinan. 2019a. Temporospatial shifts in Sandhill Crane staging in the Central Platte River Valley in response to climatic variation and habitat change. Monographs of the Western North American Naturalist 11 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mwnan/vol11/iss1/4.

Caven, A.J., D.M. Varner, and J. Drahota. 2019b. Sandhill Crane abundance in Nebraska during spring migration: making sense of multiple data points. Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences 40: 6-18.

Clements, J. F., T. S. Schulenberg, M. J. Iliff, D. Roberson, T. A. Fredericks, B. L. Sullivan, and C. L. Wood. 2016. The eBird/Clements checklist of birds of the world: v2016, accessed 30 January 2018.

Davis, C.A., and P.A. Vohs. 1993. Role of macroinvertebrates in spring diet and habitat use of Sandhill Cranes. Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Science 20: 81-86.

Dubovsky, J.A. 2018. Status and harvests of sandhill cranes: Mid-Continent, Rocky Mountain, Lower Colorado River Valley and Eastern Populations. Administrative Report, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Lakewood, Colorado, USA.

Fowler, E. 2019. Crane Moves: Sandhill Cranes arriving earlier, shifting east on Platte. Nebraskaland March 2019: 28-35.

Gerber, B.D., J.F. Dwyer, S.A. Nesbitt, R.C. Drewien, C.D. Littlefield, T.C. Tacha, and P.A. Vohs. 2020. Sandhill Crane (Antigone canadensis), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.sancra.01.

Gill, F., and D. Donsker (Eds). 2017. IOC World Bird List (v 7.3), accessed 30 January 2018.

Harner, M.J., G.D. Wright, and K. Geluso. 2015. Overwintering Sandhill Cranes (Grus canadensis) in Nebraska, USA. Wilson Journal of Ornithology 127: 457-466.

Hoffman, R. 1999. Sandhill Cranes nest in Nebraska. Nebraskaland 77: 9.

Jorgensen, J.G. 2002. The changing status of Sandhill Crane breeding in the eastern Rainwater Basin. NBR 70: 122-127.

Jorgensen, J.G. 2012. Birds of the Rainwater Basin, Nebraska. Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA.

Jorgensen, J.G., and S.J. Brenner. 2019. Notable avian nesting records from the Rainwater Basin, Nebraska — 2019. Nongame Bird Program of the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA.

Kent, T.H., and J.J. Dinsmore. 1996. Birds in Iowa. Publshed by the authors, Iowa City and Ames, Iowa, USA.

Krajewski C., J. Sipiorski, and F. Anderson. 2010. Complete mitochondrial genome sequences and the phylogeny of cranes (Gruiformes: Gruidae). Auk 127: 440–452.

Krapu, G.L., D.A. Brandt, and R.R. Cox. Jr. 2004. Less waste corn, more land in soybeans, and the switch to genetically modified crops: trends with important implications for wildlife management. Wildlife Society Bulletin 3: 127–136.

Krapu, G.L., D.A. Brandt, K.L. Jones, and D.H. Johnson. 2011. Geographic distribution of the mid‐continent population of Sandhill Cranes and related management applications. Wildlife Monographs, 175: 1-38.

Krapu, G.L.; D.A. Brandt, P.J. Kinzel, and A.T. Pearse. 2014. Spring Migration Ecology of the Mid-Continent Sandhill

Crane Population with an Emphasis on Use of the Central Platte River Valley, Nebraska. USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center. 289. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsnpwrc/289.

Krapu, G.L., Reinecke, K.J., and C.R. Frith. 1982. Sandhill cranes and the Platte River. Transactions of the North American Wildlife and Natural Resources Conference 47:542–552.

Liddick, T. 2019. 2019 Coordinated Spring Survey of Mid-continent Sandhill Cranes. United States Fish and Wildlife Service.

Lingle, G.R. 1994. Birding Crane River: Nebraska’s Platte. Harrier Publishing, Grand Island, Nebraska, USA.

Malzahn, J., A.J. Caven, M. Dettweiler, and J.D. Wiese. 2018. Sandhill Crane activity in the Central Platte River Valley in late May and early June. NBR 86: 175-180.

Pearse, A. T., G.L. Krapu, and D.A. Brandt. 2010. Effects of changes in agriculture and abundance of Snow Geese on carrying capacity of Sandhill Cranes during spring [abstract]. Proceeding of the North American Crane Workshop 11: 213.

Pyle, P. 2008. Identification Guide to North American Birds. Part II, Anatidae to Alcidae. Slate Creek Press, Bolinas, California, USA.

Pyle, P. 2025. A Practical Subspecies Taxonomy for North American Birds. North American Birds 76(1).

Rhymer, J.M., M.G. Fain, J.E. Austin, D.H. Johnson, and C. Krajewski. 2001. Mitochondrial phylogeography, subspecific taxonomy, and conservation genetics of sandhill cranes (Grus canadensis; Aves: Gruidae). Conservation Genetics 2: 203-218. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012203532300

Sherfy, M.H., M.J. Anteau, and A.A. Bishop. 2011. Agricultural Practices and Residual Corn During Spring Crane and Waterfowl Migration in Nebraska. Journal of Wildlife Management 75: 995–1003.

Sidle, J.G., H.G. Nagel, R. Clark, C. Gilbert, D. Stuart, K. Willburn, and M. Orr. 1993. Aerial thermal infrared imaging of sandhill cranes on the Platte River, Nebraska. Remote Sensing of Environment 43: 333-341.

Silcock, W.R. 2005. Spring Field Report, March-May 2005. NBR 73: 46-67.

Silcock, W.R. 2013. Winter Field Report, December 2012 to February 2013. NBR 81: 2-20.

Silcock, W.R. 2016. Spring Field Report, Mar 2016 to May 2016. NBR 84: 58- 85.

Sparling, D.W., and G.L. Krapu. 1994. Communal roosting and foraging behavior of staging Sandhill Cranes. The Wilson Bulletin 106: 62-77.

Tacha, T.C. 1988. Social organization of sandhill cranes from midcontinental North America. Wildlife Monographs No. 99.

Tremaine, M. 1970. Sandhill Cranes. NBR 38: 23-25.

Williams, G.P. 1978. The case of the shrinking channels–the North Platte and Platte Rivers in Nebraska. U.S. Geological Survey Circular 781.

Recommended Citation

Silcock, W.R., and J.G. Jorgensen. 2025. Sandhill Crane (Antigone canadensis). In Birds of Nebraska — Online.

Birds of Nebraska – Online

Updated 8 Sep 2025; map updated 16 Sep 2021