Grus americana

Status: Locally rare regular spring and fall migrant central, rare casual elsewhere. Rare casual summer visitor central and west. State and federally listed as Endangered.

Documentation: Specimen: HMM 3823 (two birds), spring 1899 Grand Island, Hall Co.

Taxonomy: No subspecies are recognized (AviList 2025).

Changes Since 2000:

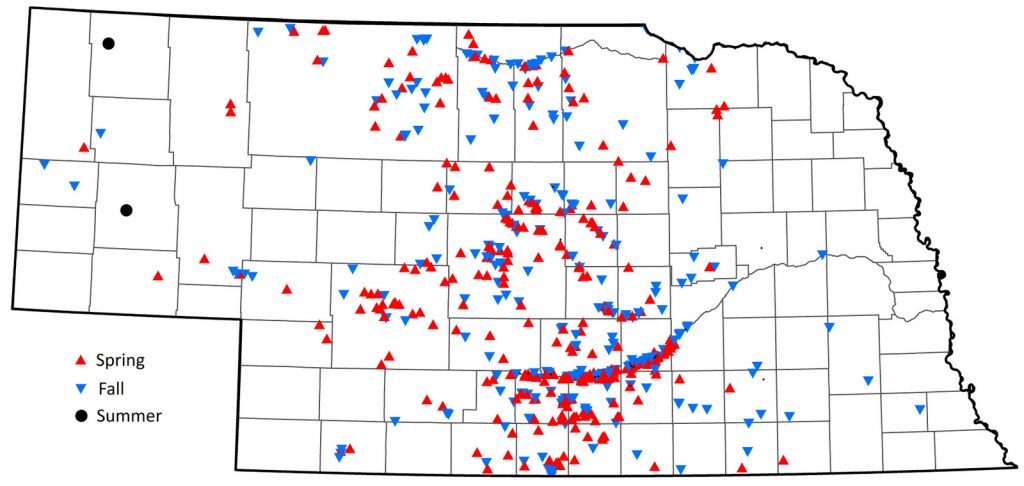

Figure 1. Spatial distribution of confirmed Whooping Crane records in Nebraska during spring (red triangles), fall (blue inverted triangles) and mid-summer (black dots) during the period 1942-2016. Based on data provided by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (2017).

Spring: Mar 3, 3, 3 <<<>>> May 15, 16, 17

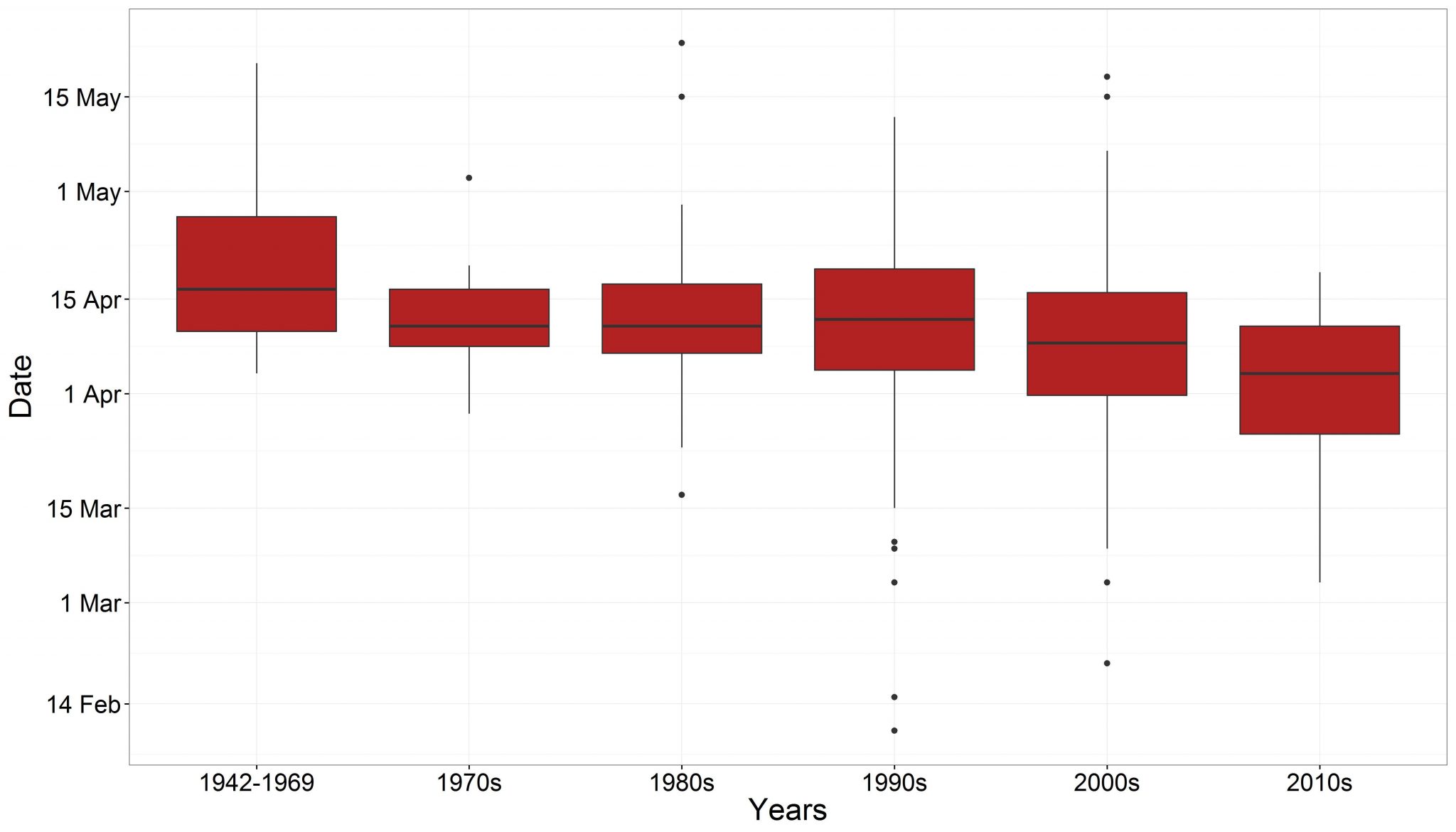

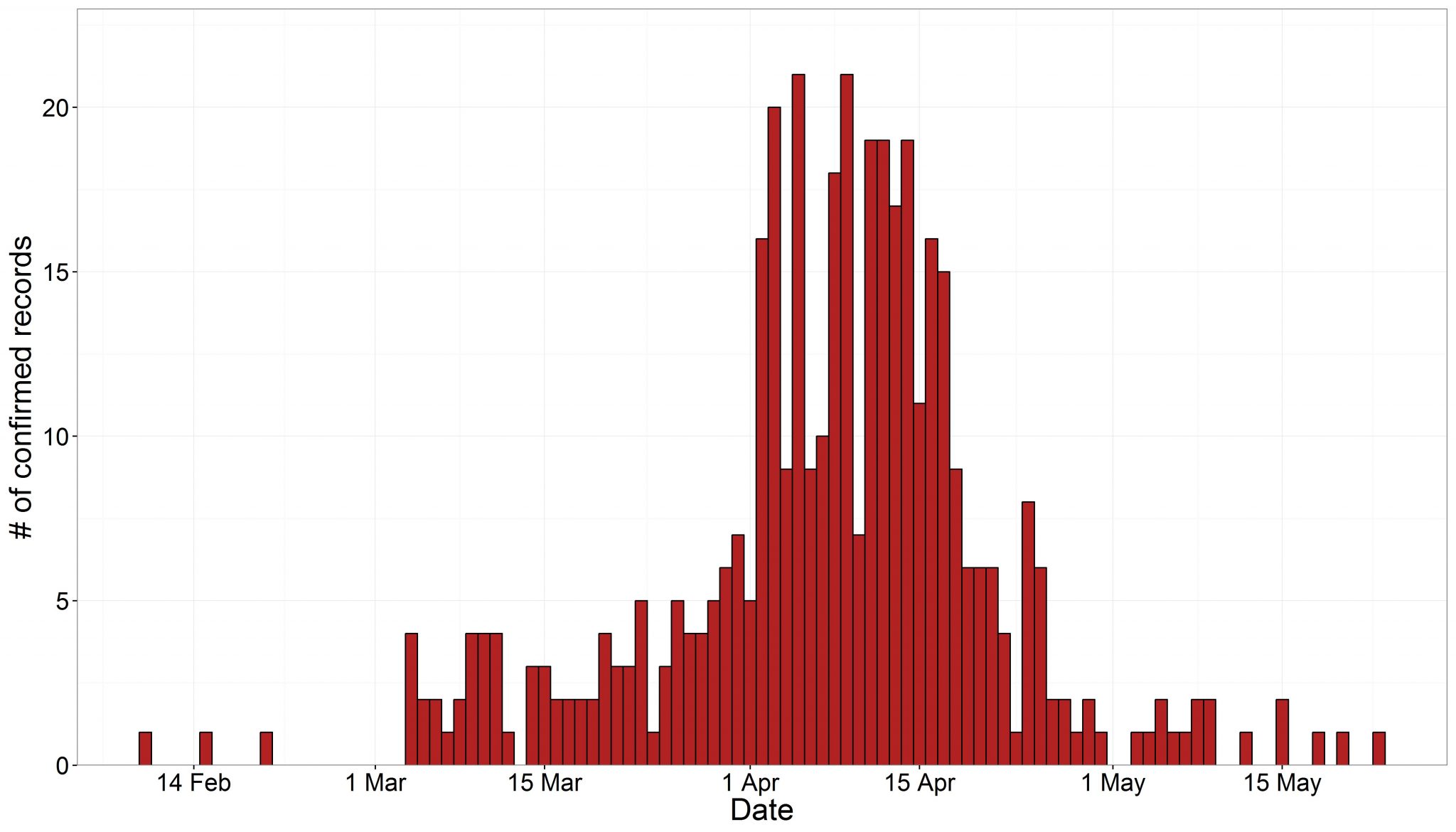

Migration primarily occurs during late March through mid-April (Figure 2), similar to the period noted by previous authors (Lingle 1994, Johnsgard 1997). More than 71% of all confirmed records (n = 391) from 1942-2016 are during the period Mar 30 – Apr 21 (Appendix, Figure 5). Average group size in spring is 3.1 (standard error ± 0.1) individuals and mean recorded stopover length is 4.2 (± 0.3) days.

Earlier spring dates are: 10 Feb 1995, a young bird which had wintered with Sandhill Cranes in Oklahoma arrived in Nebraska but retreated southward as the weather worsened (Anschutz 1995), 15 Feb-25 Mar 1998 adult in Hall Co (Omaha World Herald 18 Feb 1998), and 20 Feb–14 Apr 2009 an immature observed with Sandhill Cranes along the central Platte River, Hall Co. This was apparently the same bird that, as a lone juvenile and apparently separated from its parents, was observed near Alma, Harlan Co 15 Oct-5 Dec 2008, and wintered with Sandhill Cranes in Oklahoma.

Later reports, in May mostly, generally involve young birds which sometimes may not migrate the entire distance to the breeding grounds (see Summer). Records considered confirmed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service include 14-28 May 1988 Cherry Co, 20 May-18 Jun 1950 Phelps Co, 23-24 May 1989 Garden Co, and an adult pair that unexpectedly lingered in Jefferson County 5-21 May 2014. Other reports include eight from 24-29 May 1984 near Giltner, Hamilton Co (considered “probable”, see U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1984, and under Comments, below), 28 May 1995 Keya Paha Co (considered “probable” by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, see Anschutz 1995).

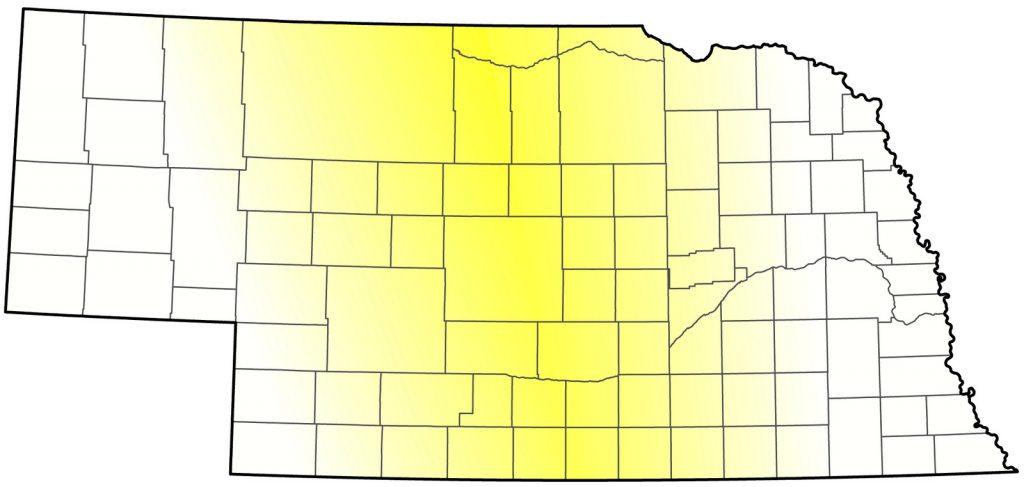

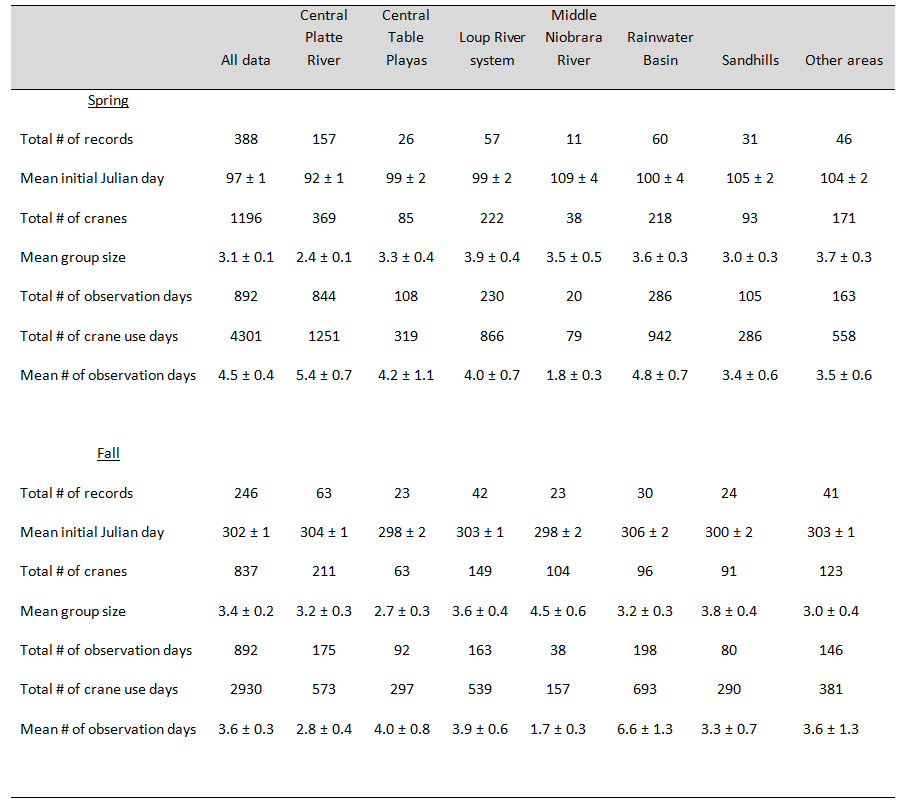

Whooping Cranes primarily migrate through central Nebraska but occasionally birds are found in the west or east (Figure 1). Of some 388 confirmed stopover locations examined (birds observed only in flight were excluded) for the period 1942-2016 (Appendix, Table 1), the greatest number (157) were from the central Platte River region with fewer from the Rainwater Basin (57), Loup River system (57), Central Table Playas (26), Sandhills (31), middle Niobrara River (11) and all other areas (46). Easterly reports are 16 Mar 1890 Richardson Co (Bent 1926), 7 May 1969 near Waterloo, Douglas Co (Cortelyou 1969), and westernmost 20-22 Apr 1987 Sioux Co and 1 Apr 1996 (Anschutz 1996), 26 Apr 1978 (Cortelyou 1978), and 27 Apr 1992 Scotts Bluff Co (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1992, Silcock 1992). Only the Sioux County record, however, is considered a confirmed record by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (2017).

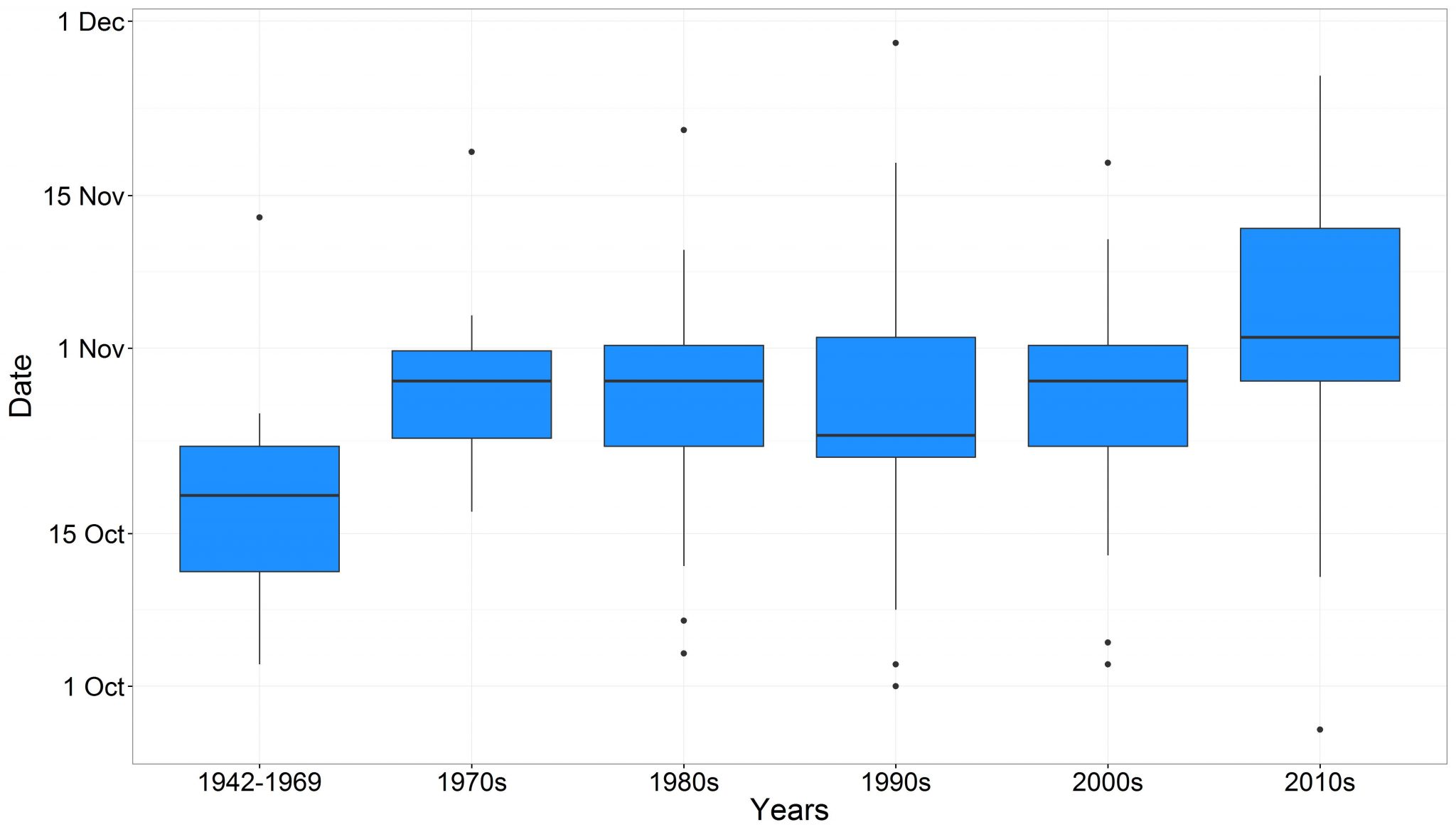

The temporal occurrence of migration through Nebraska is evolving, possibly in response to changing climate (Jorgensen and Brown 2017). Jorgensen and Brown (2017) showed that migration is occurring earlier in spring by approximately 22 days and later in fall by approximately 21 days in the Great Plains during their study period 1942-2016 (Figures 2 and 3). In Nebraska, mean initial date of confirmed spring records during the 20th Century was Apr 11 (n = 200), but mean initial date of confirmed spring records in the 21st Century through 2016 is Apr 3 (n = 191). The mean initial date of confirmed fall records during the 20th Century was Oct 27 (n = 136) but mean initial date of confirmed fall records during the 21st Century through 2016 is Oct 30 (n = 161). The first appearances of Whooping Cranes during the falls of 2016 and 2017 were relatively late and occurred on Nov 4 and Nov 1, respectively. In addition to changes in temporal occurrence, Pearse et al (2018) showed that the migration corridor through the Great Plains has gradually shifted east, possibly in response to changes in resource availability.

Figure 2. Boxplot showing the distribution of confirmed Whooping Crane spring records in Nebraska by date from 1942 to 2016. Records are grouped by decade with the exception of the years 1942-1969 which are grouped together due to the low number of records during those years. The majority of reports have occurred during late March through mid-April. Box plots show median (horizontal line in box), 25th and 75th percentiles (box), 10th and 90th percentiles (bars) and outliers (dots). Based on data provided by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (2017).

- High counts: 91 along the Platte River 28 Mar 2024, 35 in the Central Platte Valley 5 Apr 2018, and 21 near Rockville, Sherman Co 3-5 Apr 2011.

Early reports of 56 on 14 Apr 1920 (Brooking, Notes) and 40 in a flock overhead in Lincoln Co 2 Apr 1930 (Swenk 1930), are questionable; Allen (1952) discussed the discrepancy between these numbers and concurrent winter counts for the period 1914-1933 on the Texas coast, noting: “Most of these [Nebraska reported numbers] we believe to represent excessive numbers, simply as a result of honest misidentification”. Allen (1952) cited winter counts of Whooping Cranes showing the total known population to be around 45 in 1920.

Summer: There is no evidence that Whooping Cranes ever bred in Nebraska (Ducey 1988), but both Bruner et al (1904) and Bent (1926) suggested the possibility; it was known to have bred in northern Iowa until 1894 (Kent and Dinsmore 1996).

Occasionally single birds remain in summer, usually non-breeding immatures. One-year old birds hatched during the previous year may commence spring migration with parents but will separate from them before the adults reach breeding areas (Urbanek and Lewis 2015); this type of separation has been observed during spring migration in Nebraska (JGJ). Age at first breeding is around four years (Urbanek and Lewis 2015). Reports include one which remained near Whitney, Dawes Co 15 Jul-11 Oct 1991, and singles 16-23 Jul 1950 Morrill Co and 5 Aug 1990 Perkins Co.

Fall: Oct 1, 2, 3 <<<>>> Nov 23, 25, 28

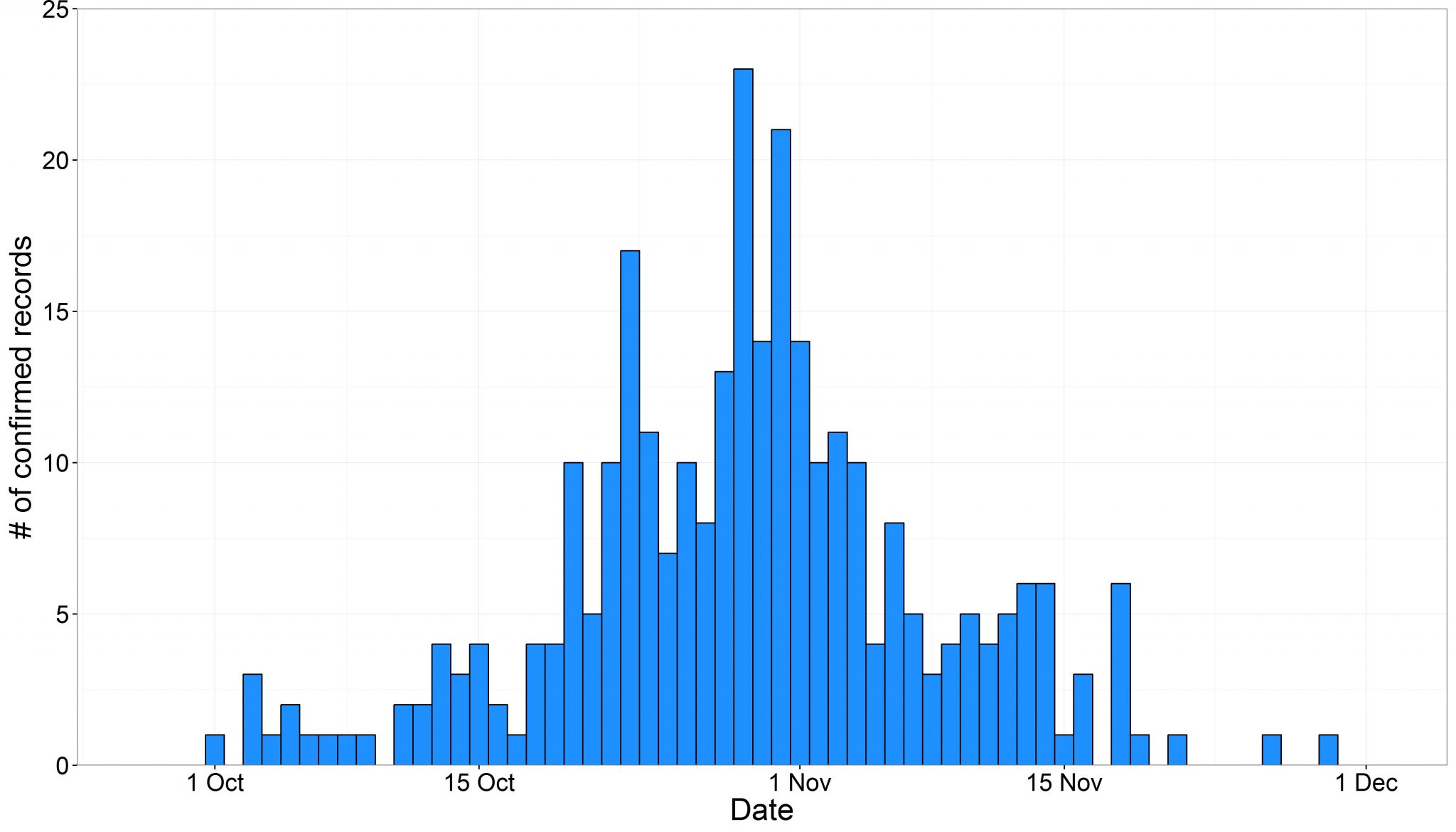

Peak movement reported by previous authors (Lingle 1994, Johnsgard 1997) was 11-31 Oct. However, a review of all records through 2016 shows 63% (n = 296) of all records are during the period Oct 20 – Nov 3 (Appendix Figure 6).

Earliest reported fall date is 27 Sep Fillmore Co, although this observation involved a brief sighting of a bird in flight and we believe it should be considered “probable”.

Later confirmed records are six from 14 Nov- 1 Dec at Father Hupp WMA, Thayer Co, a family group consisting of two adults and one juvenile at Johnson WPA, Phelps Co 9 Nov-3 Dec 1987, and a lone juvenile, apparently separated from its parents, 15 Oct-4 Dec 2008 near Alma, Harlan Co (see Spring), a family group consisting of two adults and a juvenile observed along the North Loup River in northern Greeley Co near Scotia 2-24 Dec 2017, and two adults in Hall Co that lingered until 10 Jan 2024. One flying from Sioux City, Iowa, into Dakota Co, Nebraska 25 Nov 2012 was documented and accepted by the Iowa Ornithologists’ Union (2017). However, this sighting is not considered a confirmed record by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (2017).

Average group size in fall is 3.4 (± 0.2) individuals and mean stopover length is 3.2 (± 0.3) days.

Of 246 confirmed fall stopover locations examined (birds observed only in flight were excluded) for the period 1942-2016, the greatest number (63) were from the central Platte River region with fewer from the Loup River system (42), Rainwater Basin (30), Central Table Playas (23), Sandhills (24), middle Niobrara River (23) and all other areas (41).

Figure 3. Boxplot showing the distribution of confirmed Whooping Crane fall observations in Nebraska by date from 1942 to 2016. Records are grouped by decade with the exception of the years 1942-1969 which are grouped together due to the low number of records during those years. The majority of reports have occurred during late October through early November. Box plots show median (horizontal line in box), 25th and 75th percentiles (box), 10th and 90th percentiles (bars) and outliers (dots). Based on data provided by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (2017).

Easterly records have become more numerous in fall only recently; reports are 26-27 Oct 2010 Lancaster Co, 27 Oct 2008 two adults in Johnson Co, five along the Platte River near Linwood, Butler Co28 Oct–13 Nov 2010 a pair of adults at a farm pond in Thayer Co, 31 Oct 2008 12-18 Nov 1998 a family group consisting of two adults and a juvenile at Sinninger WPA, York Co, , and 13 Nov 2015 five at Branched Oak Lake, Lancaster Co.

In the Panhandle, there are about as many fall reports as for spring. Confirmed westerly records include a juvenile with Sandhill Cranes in Scotts Bluff Co 8 Nov 1987, an adult near Mitchell, Scotts Bluff Co 16 Oct 1999, and a juvenile in western Box Butte Co 21 Oct 2013 (see below). Additional westerly reports, which are not considered confirmed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, include 24 Sep 1979 Sioux Co (Cortelyou 1980), 17 Oct 1999 Scotts Bluff Co (Silcock 1999), and 21 Oct 1990 Scotts Bluff Co (Grzybowski 1990).

Of interest are the peregrinations of a radio-tagged yearling from a reintroduced flock at White Lake, Louisiana (see Comments); this bird, L3-16, left Louisiana in May 2017, went as far north as Saskatchewan, then back-tracked south, including tracked locations in western Nebraska, prior to its appearance in Kansas 20-21 Oct. It was not sighted in Nebraska.

An injured juvenile with a damaged wing and apparently abandoned by its parents was found and photographed by a rancher 21 Oct 2013 approximately 20 miles west of Alliance, Box Butte Co. An extensive search the next day failed to find the bird and it was suspected the bird may have been preyed upon by coyotes. It is unusual for juveniles to be separated from their parents during fall migration.

High counts: 30 in flight over Valentine NWR, Cherry Co 20 Oct 2007, 16 along the Platte River in Dawson Co 12 Nov 2016, and 12 at Medicine Creek Reservoir, Frontier Co 30 Oct 2013.

A “banner year” for the species in the central Platte River Valley was fall 2021; a total of 93 were counted, including 64 together 4-10 Nov. At the Alda Bridge Overlook, Hall Co, 38 were photographed together 5 Nov.

Winter: A family group of two adults and a juvenile was at Jeffrey Island, Phelps County, 27 Jan–2 Feb 2012, during a winter when several Whooping Cranes were observed well north of their usual wintering area on the Texas Coast (Wright et al 2014). This same family group spent most of the winter in central Kansas and the birds are believed to have moved south following inclement weather and reappeared with large numbers of Sandhill Cranes unexpectedly wintering on the central Platte River (Harner et al 2015).

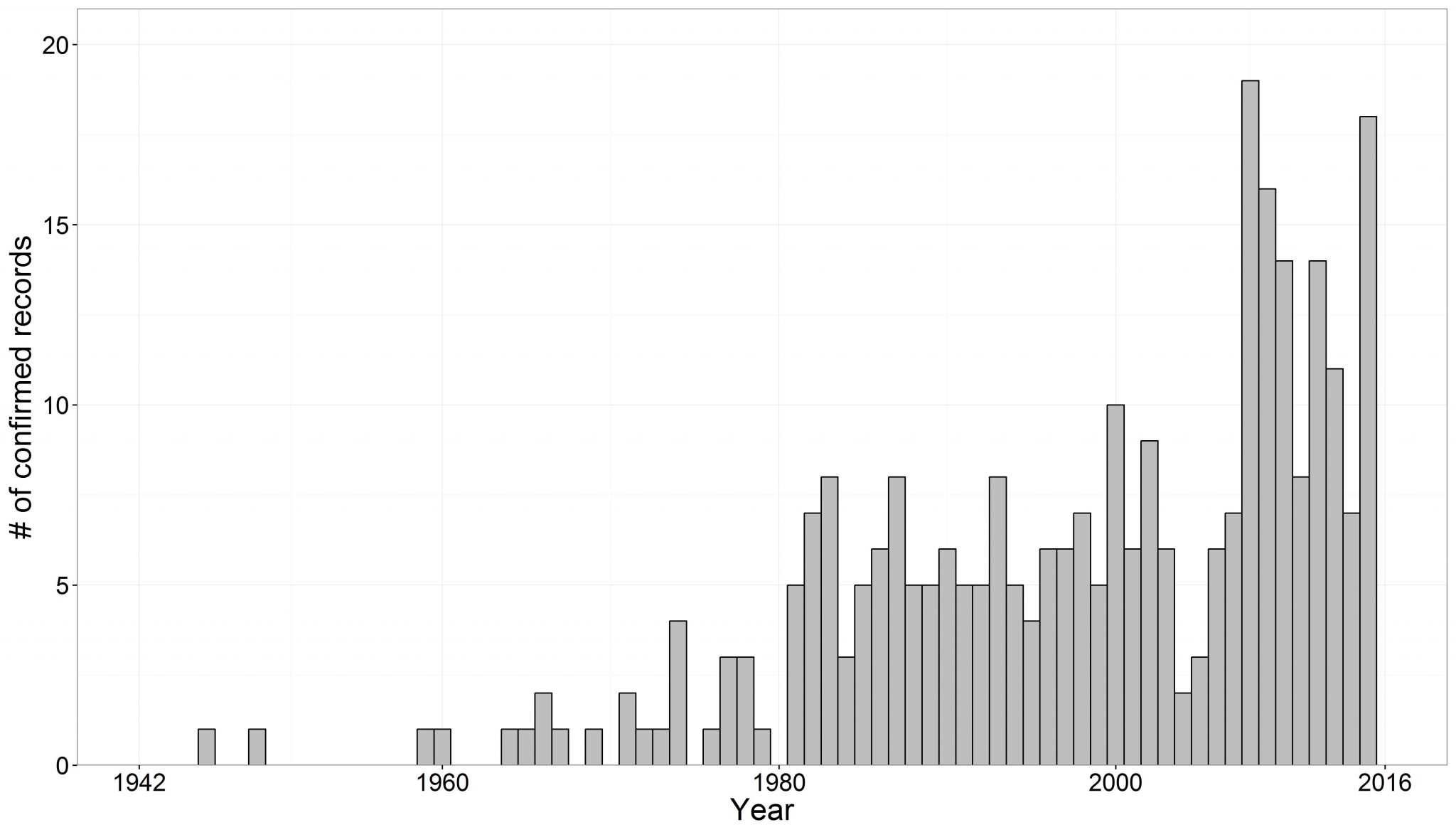

Comments: The wild flock that includes individuals that migrate through Nebraska between wintering areas along the Texas Gulf Coast and breeding sites in northeastern Alberta is often referred to as the Aransas–Wood Buffalo Population (AWBP). The historic record indicates that the species was never common (Brooking 1943), numbering perhaps less than 1500 birds in the mid-1800s (Urbanek and Lewis 2020), decreasing to about 100 in 1934 and an all-time low of 21 (plus two in captivity) in 1951 (Allen 1952). Other sources (Urbanek and Lewis 2020) state the population was as low as 15 or 16 individuals during this period; Swenk (1919) described it as “formerly common migrant, now very rare” in Nebraska. The AWBP has slowly increased in numbers. In 2000, there were an estimated 180 birds (Canadian Wildlife Service et al 2007) in the AWBP and by 2015 the mean estimate increased to 329 birds (95% confidence intervals, 293, 371; Harrell and Bidwell 2016). By the winter of 2016-17, the mean population estimate was 431 individuals (95% confidence intervals, 371, 493; Butler and Harrell 2017) and a year later surveys during the winter of 2017-18 produced a mean population estimate of 505 individuals in the AWBP (95% confidence intervals, 439, 577; Butler and Harrell 2018). See Appendix, Figure 4.

Whooping Cranes have been a focus of conservation efforts by federal and state agencies, as well as non-governmental organizations, for decades because of their small population and status as an endangered species. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has led a cooperative tracking project, with state wildlife agencies and partners, where Whooping Cranes sightings are reported to state contacts in real time, evaluated and compiled (Lewis 1988). The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service maintains a database of all reports from 1942 to the present. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service defines a “confirmed” Whooping Crane sighting as an observation made by a qualified observer (trained ornithologist or birder with experience in identifying whooping cranes; Lewis 1988). A “probable” sighting is a report wherein the observer’s physical description of the bird seems accurate, the number of birds seen is reasonable (more than 10 in a flock unlikely), behavior of the birds does not eliminate Whooping Cranes (i.e. swimming in a reservoir) and there is a good probability that the observer would provide a reliable report. An “unconfirmed” sighting is one which meets some but not all of the requirements for a probable sighting (Lewis 1988). In this species account we primarily use “confirmed” records from the database, but in some instance also refer other sightings, including those considered “probable” or “unconfirmed”. However, we clearly identify records not classified as “confirmed” in text, usually by citation.

Whooping Cranes are flexible in their use of stopover sites in Nebraska, but generally use palustrine wetlands and open river channels for roost sites and palustrine wetland and agricultural fields for feeding (Austin and Richert 2005). Sites regularly used as stopover sites during migration include the Central Platte River Valley, Rainwater Basin wetlands, Central Table Playas of Custer, Buffalo, And Valley Cos, Loup River drainage, and the Niobrara River Valley. Roosting sites on the Platte River are important, as indicated by Lingle et al (1986) and Lingle (1994). Recent years have seen construction of numerous wind-driven turbines, many within the Whooping Crane preferred migration corridor; a study by Pearse et al (2021) found that turbines were avoided by cranes, with 99% of crane locations >4.3 km from a turbine. Pearse et al (2021) estimated that about 5% of potential crane habitat was lost due to the presence of wind-turbine infrastructure.

Out of 634 confirmed records of Whooping Crane stopovers (birds observed only in flight were excluded from this total) during the period 1942-2016, 35% of the records are from the Central Platte River Valley. This area is carefully covered by aerial surveys in both spring and fall (Lingle and Howlin 2015) and aerial surveys along the Central Platte River Valley have been shown to detect twice as many birds as reported by ground observers (Sidle et al 2006). Other areas of the state (e.g. Sandhills wetlands) are rarely surveyed for Whooping Cranes and use in these areas is likely higher than the small number of records indicates.

A 53-mile stretch of the Platte River, from Shelton to Lexington, has been designated as “Critical Habitat” by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service under authority of the Endangered Species Act and 19% of all confirmed Whooping Cranes records (n = 634) during the period 1942-2016 are from this area. River roosts require a wide channel, unobstructed view for some distance, and absence of vegetation and human disturbance (Lingle et al 1986). Even though there are fewer fall records (30) from the Rainwater Basin than the Central Platte River Valley (63), more crane use days (each day an individual crane uses an area/site) have been recorded in the Rainwater Basin (693) compared to the Central Platte River Valley (573). This is because Whooping Cranes generally stopover for longer periods in the Rainwater Basin (see Appendix).

Efforts to establish additional, self-sustaining, populations in the Rocky Mountains and Florida from captive stock were unsuccessful. Additional attempts to establish an eastern migratory flock that summers in Wisconsin and winters in Florida and a non-migratory population in the vicinity of White Lake, Louisiana, have met with limited success as these populations are not presently self-sustaining. Occasionally, individuals from the eastern migratory and White Lake flocks wander and occur in the Central Flyway. In 2017, two birds from the White Lake population dispersed north and traveled through Montana, Saskatchewan and Alberta, and flew through and likely stopped in Nebraska based on satellite telemetry data. Birds from the eastern migratory flock have occurred as close as South Dakota during the summer of 2017. Observers should be aware of the possibility of these Whooping Cranes occurring in Nebraska, especially during unexpected periods.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service disclaimer: This species account includes Whooping Crane migration data from the Central Flyway stretching from Canada to Texas, collected, managed and owned by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Data were provided as a courtesy for our use. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has not directed, reviewed or endorsed any aspect of the use of these data. All data analyses, interpretations, and conclusions taken from these data are solely those of the authors.

Images

Abbreviations

HMM: Hastings Municipal Museum

NWR: National Wildlife Refuge

WMA: Wildlife Management Area (State)

Acknowledgement

Photograph (top) of Whooping Cranes at Wilkinson WMA, Platte Co, 2 April 2016 by Lauren R. Dinan.

Appendix

Table 1. Summary of Whooping Crane stopover metrics (± standard error) using data from U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (2017) by major region in Nebraska during the period 1942-2016. Confirmed records of birds observed only in flight are excluded from the summary.

Figure 4. Number of confirmed Whooping Crane observations in Nebraska by year during the period 1942-2016. Data from U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (2017).

Figure 5. Number of confirmed Whooping Crane observations during spring migration in Nebraska by day during the period 1942-2016. The initial date of a stopover used in the graphic. Data from U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (2017).

Figure 6. Number of confirmed Whooping Crane observations during fall migration in Nebraska by day during the period 1942-2016. The initial date of a stopover used in the graphic. Data from U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (2017).

Literature Cited

Allen, R.P. 1952. The Whooping Crane. National Audubon Society Research Report No. 3. National Audubon Society, New York, USA.

Anschutz, S. 1995. Whooping Crane sightings during Spring Migration, March-May, 1995. NBR 63: 82-84.

Anschutz, S. 1996. Whooping Crane sighting during March-May 1996. NBR 64: 68-70.

Austin, J., and A. Richert. 2005. Patterns of Habitat Use by Whooping Cranes During Migration: Summary from 1977-1999 Site Evaluation Data. U.S. Geological Survey, Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, Jamestown, North Dakota, USA.

AviList Core Team, 2025. AviList: The Global Avian Checklist, v2025. https://doi.org/10.2173/avilist.v2025.

Bent, A.C. 1926. Life histories of North American marsh birds. Bulletin of the United States National Museum 135 (Reprint 1963). Dover Publications, New York, New York, USA.

Brooking, A.M. Notes. Bird specimen records. Manuscript in NOU Archives, University of Nebraska State Museum, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA.

Brooking, A.M. 1943. The present status of the Whooping Crane in Nebraska. NBR 11: 5-8.

Brown, C.R., and M.B. Brown. 2001. Birds of the Cedar Point Biological Station. Occasional Papers of the Cedar Point Biological Station, No. 1.

Bruner, L., R.H. Wolcott, and M.H. Swenk. 1904. A preliminary review of the birds of Nebraska, with synopses. Klopp and Bartlett, Omaha, Nebraska, USA.

Butler, M.J., and W. Harrell. 2017. Whooping Crane Survey Results: Winter 2016–2017. US Fish and Wildlife Service, Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, Austwell, Texas, USA.

Butler, M.J., and W. Harrell. 2018. Whooping Crane Survey Results: Winter 2017–2018. US Fish and Wildlife Service, Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, Austwell, Texas, USA.

Canadian Wildlife Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. International recovery plan for the Whooping Crane. Recovery of Nationally Endangered Wildlife (RENEW), Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, and, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA.

Cortelyou, R.G. 1969. 1969 (Forty-fourth) Spring Migration and Occurrence Report. NBR 37: 50-71.

Cortelyou, R.G. 1978. 1978 (Fifty-third) Spring Migration and Occurrence Report. NBR 46:66-85.

Cortelyou, R.G. 1980. 1979 (Twenty-second) Fall Occurrence Report. NBR 48: 3-15.

Ducey, J.E. 1988. Nebraska birds, breeding status and distribution. Simmons-Boardman Books, Omaha, Nebraska, USA.

Grzybowski, J.A. 1990. Southern Great Plains Region. American Birds 44: 1152-1154.

Harner, M.J., G.D. Wright, and K. Geluso. 2015. Overwintering Sandhill Cranes (Grus canadensis) in Nebraska, USA. Wilson Journal of Ornithology 127: 457-466.

Harrell, W., and M. Bidwell. 2016. Whooping Crane recovery activities, 2015 breeding season to 2016 spring migration. US Fish and Wildlife Service, Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, Austwell, Texas, USA.

Iowa Ornithologists’ Union. 2017. Whooping Crane records. Iowa Records Committee reports of Iowa rare bird records, accessed 21 February 2018.

Johnsgard, P.A. 1997. The birds of Nebraska and adjacent plains states. Occasional Papers No. 6, Nebraska Ornithologists’ Union. Lincoln, Nebraska, USA.

Jorgensen, J.G., and M.B. Brown. 2017. Temporal Migration Shifts in the Aransas-Wood Buffalo Population of Whooping Cranes (Grus americana) across North America. Waterbirds 40: 195-206.

Kent, T.H., and J.J. Dinsmore. 1996. Birds in Iowa. Publshed by the authors, Iowa City and Ames, Iowa, USA.

Korpi, R.T. 1991. Fall 1990 Occurrence Report. NBR 59: 8-28.

Lewis, J.C. 1992. The contingency plan for federal-state cooperative protection of whooping cranes. Pages 295-299 in D. A. Wood, ed. Proceeding of the 1988 North American crane workshop, Florida: State of Florida Game and Fresh Water Fish Commission, Lake Wales, Florida, USA.

Lingle, G.R. 1994. Birding Crane River: Nebraska’s Platte. Harrier Publishing, Grand Island, Nebraska, USA.

Lingle, G.R., and S. Howlin. 2015. Implementation of the Whooping Crane Monitoring Protocol: Spring 2015. Final Report Prepared by AIM Environmental Consultants and Western Ecosystems Technology, Inc. for committees of the Platte River Recovery Implementation Program, Kearney, Nebraska, USA.

Lingle, G.R., K.J. Strom, and J.W. Ziewitz. 1986. Whooping Crane Roost Site Characteristics on the Platte River, Buffalo County, Nebraska. NBR 54: 36-39.

Pearse, A.T., K.L. Metzger, D.A. Brandt, J.A. Shaffer, M.T. Bidwell, and W. Harrell. 2021. Migrating whooping cranes avoid wind‐energy infrastructure when selecting stopover habitat. Ecological Applications. DOI: 10.1002/eap.2324.

Pearse, A.T., M. Rabbe, L.M. Juliusson, M.T. Bidwell, L. Craig-Moore L, D.A. Brandt, W. Harrell. 2018. Delineating and identifying long-term changes in the whooping crane (Grus americana) migration corridor. PLoS ONE 13(2): e0192737. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0192737

Sidle, J.G., W.G. Jobman, and C.A. Faanes. 2006. Aerial searches for Whooping Cranes along the Platte River, Nebraska. NBR 74: 95-98.

Silcock, W.R. 1992. Spring Field Report, March-May 1992. NBR 60: 79-149.

Silcock, W.R. 1999. Fall Field Report, August-November 1999. NBR 67: 118-139.

Swenk, M.H. 1919. The Birds and Mammals of Nebraska. Contributions of the Department of Entomology No. 23. Lincoln, Nebraska.

Swenk, M.H. 1930. Letters of Information 50: 3.

Urbanek, R.P. and J.C. Lewis. 2020. Whooping Crane (Grus americana), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.whocra.01.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2017. Cooperative Whooping Crane tracking project database 1942-2016. Unpublished data, U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Nebraska Field Office, Grand Island, Nebraska, USA.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1984. Spring 1984 Whooping Crane records in Nebraska. NBR 52: 46-47.

Wright, G.G., M.J. Harner, and J.D. Chambers. 2014. Unusual wintering distribution and migratory behavior of the Whooping Crane (Grus americana) in 2011-2012. Wilson Journal Ornithology 126: 115-120.

Recommended Citation

Silcock, W.R., and J.G. Jorgensen. 2025. Whooping Crane (Grus americana). In Birds of Nebraska — Online. www.BirdsofNebraska.org

Birds of Nebraska – Online

Updated 1 Aug 2025