Anas platyrhynchos PLATYRHYNCHOS

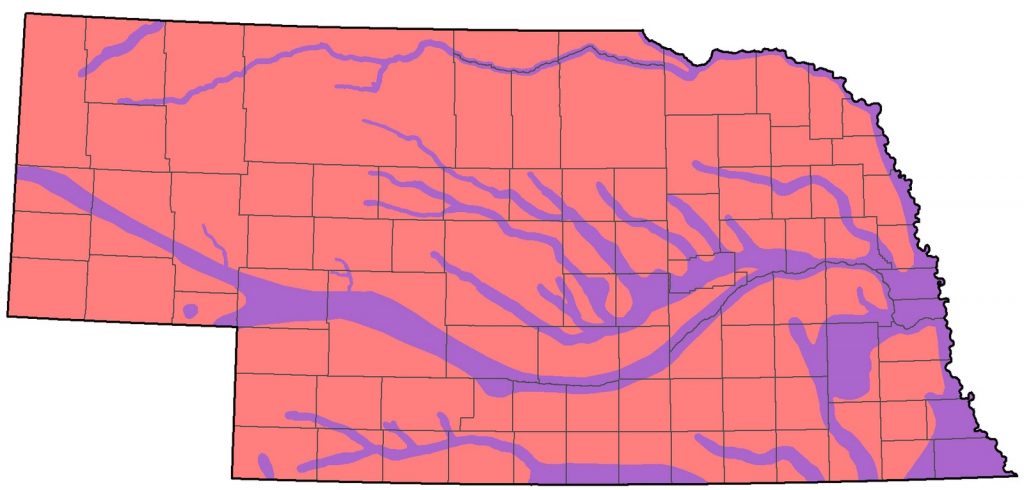

Status: Abundant regular spring and fall migrant statewide. Common regular breeder statewide. Common, locally abundant, regular winter visitor statewide.

Documentation: Specimen: UNSM ZM7674, 11 Apr 1916 Lancaster Co.

Taxonomy: Two subspecies are currently recognized, worldwide nominate platyrhynchos, and conboschas, confined to Greenland (AviList 2025).

Nebraska birds are presumed platyrhynchos.

The history of Mallard in North America and its current genetic structure can be traced to two probable invasions by European Mallards and, more recently, extensive introductions of game farm Mallards for hunting purposes (Lavretsky et al 2019). The first invasion, presumably by an ancient monochromatic Mallard forbear, was followed by differentiation into the familiar monochromatic North American species, American Black Duck A. rubripes, Mexican Duck A. diazi, and Mottled Duck A. fulvigula (McCracken et al 2001). Meanwhile in Europe, the ubiquitous dichromatic Mallard arose, and subsequently spread into North America via Alaska, and expanded eastward. Finally, multiple releases beginning in the 1980s, mostly in the eastern US, of game farm-raised Mallards resulted in extensive hybridization with American Black Duck (Lavretsky et al 2019). Avise et al (1990) discovered two haplotypes (sets of DNA variations that tend to be inherited together) in North American Mallards. It appears that the type B haplotype arose in North America among hybrids between Mallard and “black ducks” (including American Black, Mottled and Mexican), while pure (European) Mallards are type A. Lavretsky et al (2019) designated these haplotypes Old World A and New World B.

Hybridization by American Black Duck with Mallard was limited if not non-existent prior to the 1970s when Mallard was uncommon in eastern North America (Johnsgard 1975), but increased greatly in the 1980s and 1990s as introductions in the east occurred. The potential for American Black Duck being genetically swamped was a major concern (Mank et al 2004), but more recently, genomic studies by Lavretsky et al (2019) have shown that there is minimal introgression beyond the fairly limited hybrid zone and that F1 birds tend to backcross with one or the other parental form, resulting in essential elimination in some three generations of introgressed genes. As stated by Lavretsky et al (2019), “our results do not support the eastern hybrid swarm hypothesis or predict the subsequent genetic extinction of the black duck…”, and further, these authors concluded that, while hybridization may be quite prevalent, “such acts may simply be wasted reproductive effort”. A hybrid swarm requires essentially unlimited back and forth gene flow, which Lavretsky et al (2019) determined not to be present in the case of Mallard and American Black Duck.

Identification of Mallard, American Black Duck, and hybrids in the field using phenotypic characters was shown by Lavretsky et al (2019) to be rather inaccurate and similar to the errors reported amongst Mallard and Florida Mottled Duck before a genetically vetted field key was developed by Bielefeld et al (2016). Lavretsky et al (2019) summarized misidentifications as follows, as determined by comparison of genomes with field identifications of birds in the hybrid zone: “at least ~20% of all phenotypically identified mallards and black ducks were incorrect and possessed hybrid ancestry. Furthermore, only ~60% of phenotypically identified hybrids were true hybrids with ~12% and ~25% of remaining samples being actually “pure” mallards or black ducks, respectively”.

For Nebraska records of Mallard hybrids with other species, see Gadwall x Mallard (hybrid), American Wigeon x Mallard (hybrid), Mallard x American Black Duck (hybrid), Mallard x Mexican Duck (hybrid), and Mallard x Northern Pintail (hybrid).

It should be noted that intersex individuals can occur among Mallards that are sometimes identified as hybrids. Such birds are females that develop male plumage features, possibly as they age, but retain bill colors typical of an adult female. A discussion and photos can be found here.

Commonly reported to eBird are Nebraska “Domestic type” Mallards. These are primarily tame ducks found in parks and often fed by the public in higher population areas in eastern Nebraska and along the Platte and Noth Platte river valleys southward. A common variety is the large white goose-like duck, but a wide range of colors and shapes occur. An interesting discussion of domestic type Mallards and Muscovy Ducks can be found here.

Spring: Mallard numbers increase by late-winter as water opens up, and numbers quickly rise to peak counts in early Mar. Some 50% of the mid-continent population uses the Rainwater Basin in spring (Gersib et al 1989).

- High counts: 200,000 at Harlan Co Reservoir, Harlan Co 9 Mar 2003, 150,000 at Sutherland Reservoir, Lincoln Co 2 Mar 2023, 81,000 in the eastern Rainwater Basin 17 Mar 2001, and 23,792 at North Platte NWR, Scotts Bluff Co 11 Mar 1997.

Summer: Mallards breed statewide in a variety of habitats, including traditional wetland-grassland mosaics but also in suburban and urban settings. The most important breeding areas in Nebraska are the Sandhills and the Rainwater Basin (Baldassare 2014). In the Rainwater Basin, it is the second most common nesting duck species behind only Blue-winged Teal; Evans and Wolfe (1967) found 18% of all duck nests (n = 206) during 1958-1962 to be this species. Harding (1986) found 16% of all duck nests (n= 723) during 1981-1985 to be of Mallard. Nests are usually on the ground, although a hen made a nest seven feet above the ground in a hollow stump in Sioux Co in 2002; there were seven eggs present on 7 Jul (Mollhoff 2004).

Mallard drakes leave nesting sites in May and Jun in molt migration, commonly at locations in Nebraska. A male was undergoing pre-alternate molt into “eclipse” plumage (Howell 2010) near North Platte, Lincoln Co 9 Jul 2007 and 159 Mallards (sexes not noted) at Holmes Lake, Lancaster Co 29 Jul 2019 and 95 there 4 Jul 2024 were likely aggregations of recent broods and molt migrants; the 2024 number was probably a result of drying conditions in nearby breeding locations. Post-breeding females join these flocks later, prior to primary fall migration (Palmer 1976).

- Breeding phenology:

Eggs: 3 Apr-27 Jul.

Dependent fledglings: 28 Apr-3 Sep.

Fall: Major movements are much more discernible in the fall than spring. Numbers begin to increase in the state in mid-Oct and achieve peak counts in late Nov through mid-Dec.

Bands taken by Nebraska hunters from fall and early winter kills indicate that the majority of individuals were produced in the prairie provinces of Canada. Two banded Mallards were recovered in Burt Co 5 Dec 2019, one banded in South Dakota 14 years prior, the other in Kentucky, also 14 years prior, the oldest birds encountered in the reporter’s 25 years of waterfowling (Eric Bents, personal communication).

- High counts: 150,000 at Harlan Co Reservoir 15 Dec 2000, 100,000 at Sutherland Reservoir, Lincoln Co 30 Dec 2011, 100,000 there 18 Nov 2020, 88,765 at North Platte NWR 28 Nov 1995, and 73,792 there 25 Nov 1997.

Winter: Winter concentrations are dependent on available open water and exposed grain in nearby fields and feedlots. Nebraska hosts some 17.5% of the North American wintering population (Baldassare 2014).

- High counts: 200,000 at Sutherland Reservoir 30 Jan 2024, 124,000 there 5 Jan 2019, and 50,000-80,000 there 9 Jan 2011.

Images

Abbreviations

NWR: National Wildlife Refuge

UNSM: University of Nebraska State Museum

Acknowledgements

We thank Steven Mlodinow for important literature citations.

Literature Cited

AviList Core Team, 2025. AviList: The Global Avian Checklist, v2025. https://doi.org/10.2173/avilist.v2025.

Avise, J.C., C.D. Ankney, and W.S. Nelson. 1990. Mitochondrial gene trees and the evolutionary relationship of Mallard and Black Ducks. Evolution 44: 1109-1119.

Baldassarre, G. 2014. Ducks, geese, and swans of North America. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

, A. , J.C. 2016. Is it a mottled duck? The key is in the feathers. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 40, 446– 455. https://doi.org/10.1002/wsb.665

Evans, R.D., and C.W. Wolfe. 1967. Waterfowl production in the Rainwater Basin area of Nebraska. Journal of Wildlife Management 33: 788-794.

Gersib, R.A., B. Elder, K.F. Dinan, and T.H. Hupf. 1989. Waterfowl values by wetland type within Rainwater Basin wetlands with special emphasis on activity time budget and census data. Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Grand Island, Nebraska, USA.

Harding, R.G. 1986. Waterfowl nesting preferences and productivity in the Rainwater Basin, Nebraska. Master’s thesis, Kearney State College, Kearney, Nebraska, USA.

Howell, S.N.G. 2010. Molt in North American Birds. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Johnsgard, P.A. 1975. Waterfowl of North America. University of Indiana Press, Bloomington, Indiana, USA.

Lavretsky, P., T. Janzen, and K.G. McCracken. 2019. Identifying hybrids & the genomics of hybridization: Mallards & American black ducks of Eastern North America. Ecology and Evolution 9: 3470-3490. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.4981.

Mank, J.E., J.E. Carlson, and M.C. Brittingham. 2004. A century of hybridization: Decreasing genetic distance between American Black Ducks and Mallards. Conservation Genetics 5 (3):395-403. doi: 10.1023/B:COGE.0000031139.55389.b1.https://doi.org/10.1023/B:COGE.0000031139.55389.b1.

McCracken, K.G., W.P. Johnson, and F.H. Sheldon. 2001. Molecular population genetics, phylogeography, and conservation biology of the mottled duck (Anas fulvigula). Conservation Genetics 2: 87-102.

Mollhoff, W.J. 2004. The 2001 Nesting Report. NBR 72: 99-103.

Palmer, R.S., ed. 1976. Handbook of North American birds. Vol. 2. Waterfowl (Parts 1 and 2). Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

Recommended Citation

Silcock, W.R., and J.G. Jorgensen. 2025. Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos). In Birds of Nebraska — Online. www.BirdsofNebraska.org

Birds of Nebraska – Online

Updated 5 Jul 2025